A shared challenge: Attitudes about climate action in France and Germany

Contents

- How urgently does the public want climate action?

- Who should act, and at what cost?

- What is the value of European cooperation for citizens?

- What solutions are preferred? Which ones are rejected?

- What do attitudes to energy sources look like?

- Which groups are pro and anti-climate action?

*** Please note: this factsheet is part of a CLEW cross-border cooperation, exploring the Franco-German approaches to climate and energy and how these affect the vision of the EU’s energy future. You can find the full dossier here.***

1. How urgently does the public want climate action?

Like in most other European countries, climate change and other environmental issues are regularly listed among the most pressing issues that German and French citizens think their governments need to tackle. In a 2021 Eurobarometer Special survey of the EU’s 27 member states on attitudes towards climate action, roughly 80 percent of respondents in France and Germany agreed with the statement that climate change poses “a very serious problem” and needs to be addressed with urgency. In Germany, climate change topped the list of urgent global challenges, with 28 percent of respondents saying that climate change is the most serious problem facing the planet. This share was significantly higher than in France, where 18 percent of respondents agreed, on par with the EU average. Hunger and water scarcity were the greatest global concerns for French respondents.

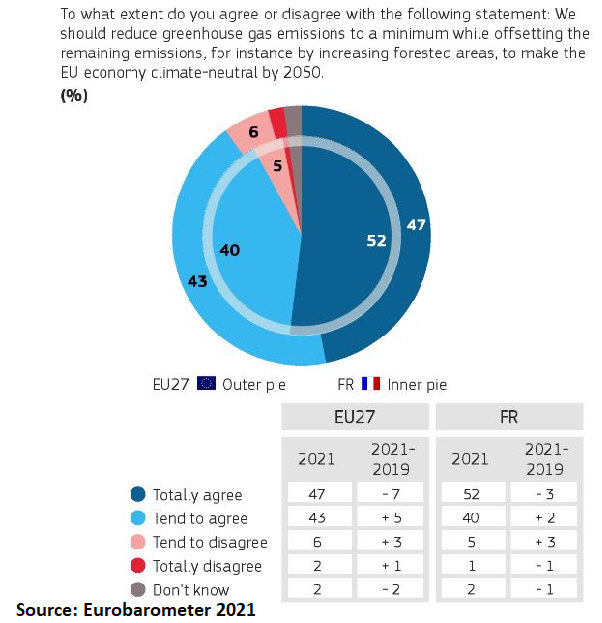

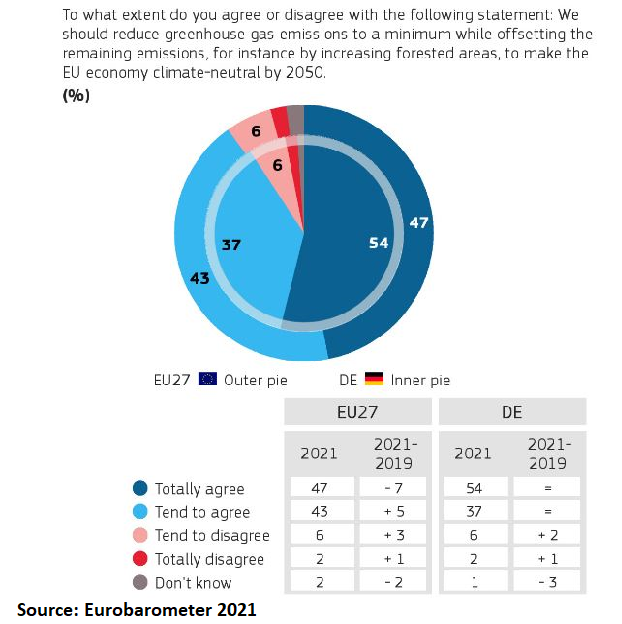

Over 90 percent of respondents in both countries agreed with the idea that greenhouse gases should be reduced to a minimum and the remainder offset to achieve the EU goal of climate neutrality by 2050.

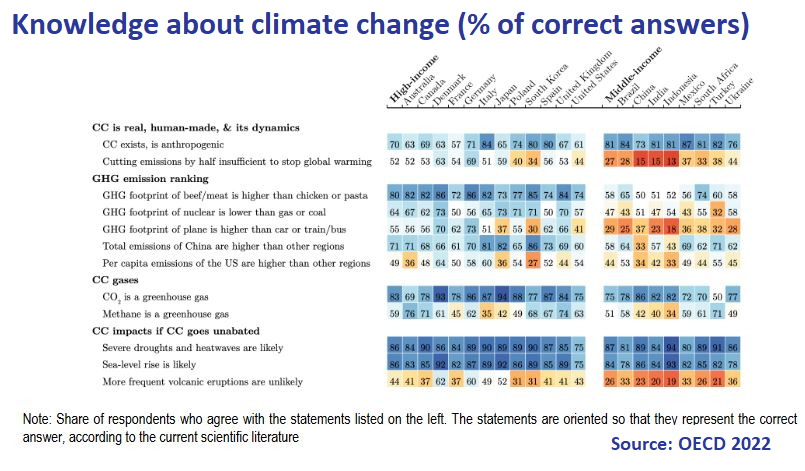

The similarly high level of concern for climate between the countries was confirmed in another survey from the OECD in 2022, where 81 percent of respondents in both countries said it is an important problem and 77 percent answered that their country should fight it. However, the survey showed that there seems to be more literacy about the causes and effects of climate change in Germany than in France. German respondents on average scored better in answering questions on emissions and energy generation than their French counterparts. This also was true with respect to knowledge about nuclear power, which dominates the energy mix in France but was phased out in Germany in April 2023.

France ranked as the most pessimistic country in the OECD survey regarding perceived effectiveness of environmental policies, followed closely by Germany and the United States.

A major 2023 survey of Germany by the government-sponsored Ariadne research project found that the 2022 energy crisis increased awareness among many citizens that more resolute climate action is needed. A majority of respondents “desired policies that equally address overcoming the energy crisis and protecting the climate,” the survey found.

Similarly, a large-scale survey by French grid operator RTE, published in the wake of the energy crisis, found in 2023 “a real awareness among the French about climate change and the need to transform lifestyles.” This attitude could become a crucial prerequisite given the considerable behavioural changes needed to achieve climate neutrality, RTE noted.

2. Who should act, and at what cost?

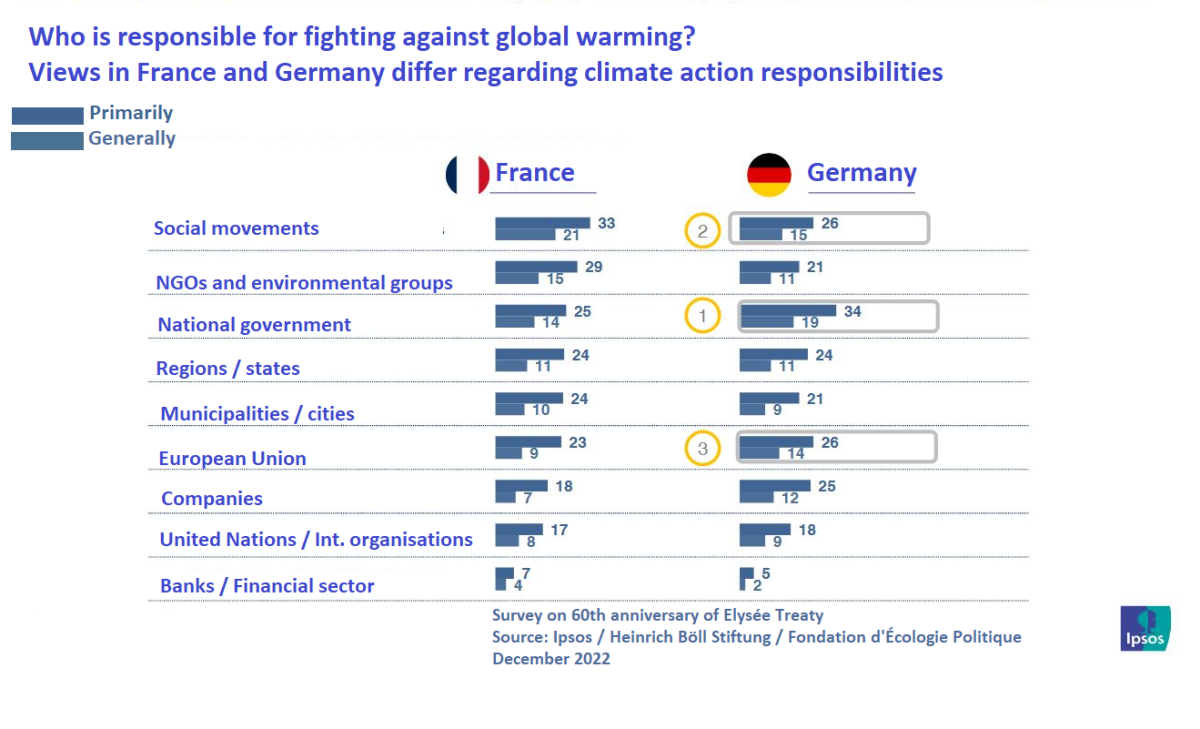

While there is a comparably high level of concern about the challenges that climate change poses, public opinion in both countries differs when it comes to climate action. The clearest differences emerge over which actors should be held responsible for taking action in the first place.

According to the Eurobarometer survey, business and industry were considered the most responsible actors by most Germans (72%), much higher than the EU average of 58 percent (multiple answers were possible). In France, which has a significantly smaller industrial sector than Germany, only 52 percent said business and industry are responsible for taking action. Most French respondents (62%) said responsibility rested with the EU, higher than the EU average (57%). For Germany, the figure was 63 percent.

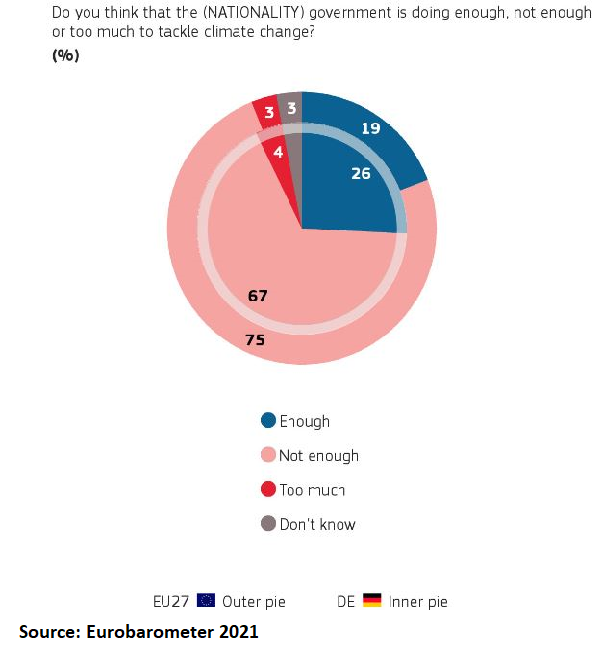

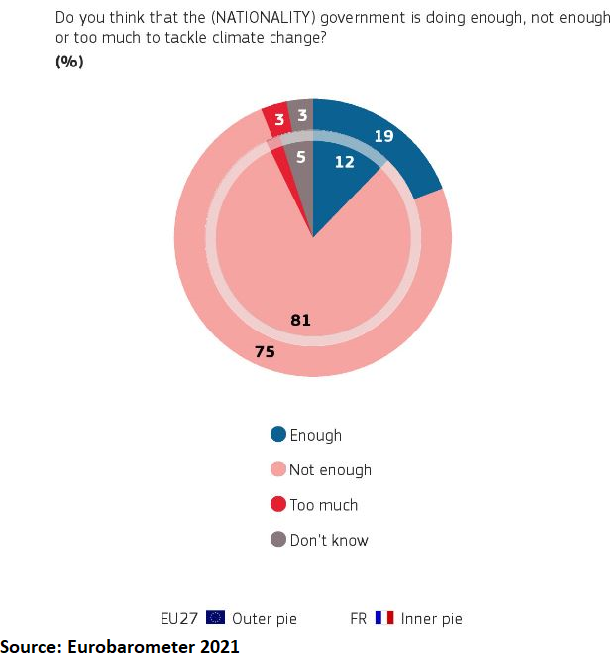

Their national government was responsible to 63 percent of German and 61 percent of French respondents. At the same time, the share of respondents saying the government is not doing enough on climate was much higher in France (81%) than in Germany (67%).

The need to take individual responsibility for climate change was cited by roughly half of the population in both countries, the Eurobarometer Special survey showed. However, with 56 percent in Germany the share was still clearly higher than in France, where 46 percent agreed with the idea. In addition, the number of people who answered that they had taken personal climate action measures in the past six months was higher in both Germany (79%) and France (69%).

There was general agreement by more than two thirds in either country that the cost of climate action ultimately is much smaller than the cost of damages from climate change if no action is taken, with a slightly higher proportion agreeing in Germany (74%) than in France (69%).

Seventy percent of French respondents in a 2022 survey by Destin Commun (More in Common) answered that they consider the current economic model to be incompatible with environment protection and tackling the climate crisis and were willing to do more on a daily basis to combat climate change.

In a parallel survey in Germany commissioned by public broadcaster SWR, 46 percent agreed with the statement that economic growth must be reduced in order to protect the climate – while exactly the same share of respondents disagreed with the idea.

At the same time, however, 45 percent of French respondents in the Destin Commun survey answered that they would not give up any purchasing power in return for climate action. The cost of living should be given priority in situations where this conflicts with climate action, even if this comes at the expense of environmental protection, the survey found.

In a different survey by consultancy EY, 48 percent of respondents in Germany said a secure energy supply should be the priority for policymakers and 40 percent said it should be lower energy prices. Only 12 percent said climate protection should be the guiding principle for government action during the energy crisis.

3. What is the value of European cooperation for citizens?

The EU is seen as a key actor responsible for taking effective climate action in both Germany and France, as about two thirds of respondents in either country stated in the Eurobarometer survey. Around 81 percent of respondents in both countries in a bi-national survey by the German Heinrich Böll Foundation and the French Ecological Policy Foundation said that Franco-German cooperation is indispensable for the success of the European Union. Tackling energy security was named as the number-one priority for policymakers in their bilateral efforts, with 47 percent of French and 49 percent of German participants considering it a priority. Effective cooperation on climate action also ranked high and was considered a priority by 31 percent of French and 33 percent of German respondents.

Looking to prevailing public opinion in both countries showed that a coordinated European approach is “indispensable,” said Mathieu Gallard from French pollster Ipsos. The view from France and Germany was that people expect proactive thinking from the Franco-German couple on energy and climate. “This opinion clearly transcends political fault lines in both countries,” Gallard added.

4. What solutions are preferred? Which ones are rejected?

While survey respondents often generally agree that there is a need to reduce emissions, they are much less likely to align with actual policy proposals to address emissions reduction. However, the containment measures and lockdowns during the coronavirus pandemic in both countries demonstrated that far-reaching changes to lifestyles and consumption habits are possible. Triggered by the imposition of covid restrictions in 2020, France saw a historic fall in its emission of 8.3 percent after adjusting for annual climate variation. Energy consumption in Germany dropped 8 percent in the same year, and greenhouse gas emissions fell about 9 percent.

The idea of energy sufficiency (‘sobriété’) has grown in importance since the forced cuts to consumption that the pandemic ushered in. In contrast to efficiency, it does not denote less energy use for the same level of consumption, but rather reducing energy demand through behaviour change. The 2022 Destin Commun survey found that 73 percent of French people believe that sufficiency is a favourable component of climate action. The RTE survey in the following year showed that sufficiency has“become widely accepted as a virtuous and necessary approach.” Only a minority associated it with economic decline or a “step backwards,” it concluded.

In Germany, almost 90 percent of respondents in a YouGov survey from December 2022 said they had started to conserve more energy since the beginning of the energy crisis. Sixty percent said they had reduced their demand for heating energy by lowering temperatures or turning off the heating altogether. Forty percent said they are showering, and bathing less often, with only 8 percent stating they do not try to save energy at all.

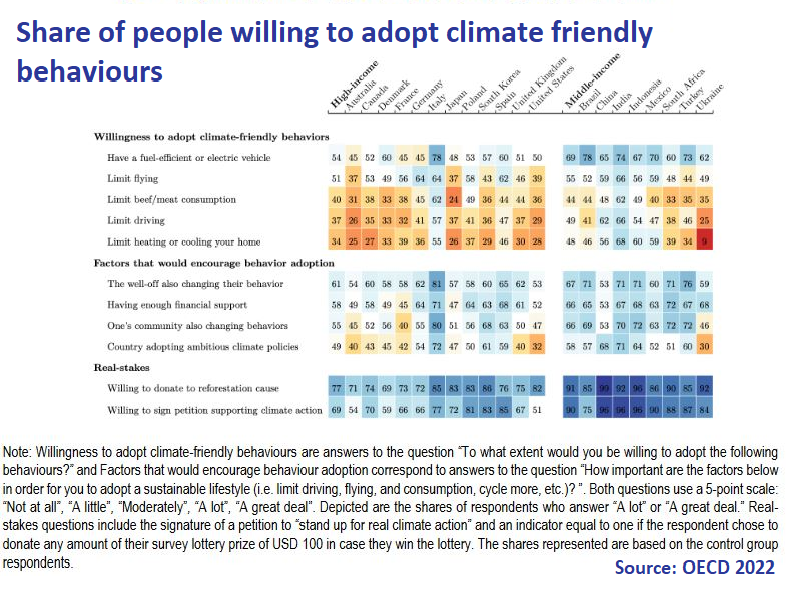

The Eurobarometer survey probed the measures people were ready to take beyond the immediate impact of the energy crisis. The number-one measure respondents cited in both countries was reducing and recycling waste, which 83 percent of French and 81 percent of German survey participants listed (EU=75%). Only 23 percent in France answered they would regularly use more environmentally friendly alternatives to the car, compared to 51 percent in Germany, considerably above the EU average of 30 percent. Reducing meat consumption was cited as a potential method for reducing personal carbon footprints by a greater share in both countries than the EU average. Forty percent in France and 51 percent in Germany answered that they would consider reducing meat consumption, versus 31 percent for the European average.

In the OECD survey, attitudes towards potential routes for emission reduction were similar across several categories in both countries. This was notably the case for the introduction of carbon taxes with cash redistribution, which was backed by 29 percent in France and 28 percent in Germany. Perceptions diverged over limiting flying, which 64 percent in Germany and only 56 percent in France supported, and reducing driving, which was supported by 41 percent in Germany and 32 percent in France. Similarly, 38 percent in Germany were in favour of removing subsidies for cattle farming and a 40 percent tax on beef and dairy products, while the figures for France were 28 percent and 29 percent, respectively.

"Heroic" emission reduction scenario for France

The consultancy firm Carbone 4 estimated in June 2019 that in France, an exemplary individual commitment (deemed "heroic") could, in principle, reduce the average carbon footprint by almost 45 percent. It showed that significant changes to individual behaviours (becoming vegetarian, cycling, no flying...) can reduce carbon footprints by 25 percent at best. Actions involving investment – thermal renovation, changing boilers, replacing a petrol or diesel vehicle with an electric one – would add another reduction of 20 percent. Far from this ideal scenario, it eventually estimated the impact of "moderate" individual commitments (all types of action taken together) would lead to 20 percent reduction in emissions. However, this study showed that individual commitment was insufficient and that the remaining part of the reduction in emissions depended on investments and regulation that are under the jurisdiction of governments and corporations.

5. What do attitudes to energy sources look like?

Opinions on how energy should be generated in the future differ between France and Germany. Renewables clearly dominated among German respondents, according to a survey published in 2022 by the German Federal Environmental Foundation (DBU). Seventy-five percent of respondents called for a greater use of solar PV, 65 percent for more wind power and for scaling up hydrogen production with renewables. One in four (25%) answered that the country should use more nuclear energy in the future, even though the technology was scheduled to be phased out at the end of 2022, with the decommissioning of the last plants ultimately taking place in April 2023. However, a different survey by public broadcaster ZDF, conducted in the summer of 2022, found that two thirds (65%) of respondents in Germany would have wished to keep the nuclear plants running longer to provide backup during the energy crisis. At the same time, 93 percent said renewables should be built faster.

In the DBU survey, merely six percent said natural gas should play a greater role in the future and five percent favoured coal. However, in the ZDF survey, 61 percent also answered they would accept coal plants running longer to ensure a stable energy supply.

In France, hydro power was named as the most popular energy source, with 90 percent of respondents in a 2022 survey from renewable power association Syndicat d’Energies Renouvelables (SER) answering that this form of energy generation has “a good image.” This was followed by geothermal energy (86%) and renewables gases (85%), usually derived from biomass. Solar PV (85%) was significantly more popular than wind power, but a clear majority still answered that both offshore (66%) and onshore (64%) wind turbines are generally a good thing. This was markedly higher than support for the country’s most important power source, nuclear energy, of which 48 percent answered that they had a positive view of it. 52 percent in the survey said they had a negative view of nuclear energy. However, perceptions of nuclear energy in France may vary depending on the survey. In a different poll carried out by OpinionWay, two thirds (66%) of respondents were found to support a resurgence of nuclear power in the country, up from 39 percent in 2016.

Natural gas was the only fossil fuel in the SER survey with a good or acceptable image (43%), whereas oil (21%) and coal (19%) clearly scored worst among all forms of energy generation in France. Asked about the speed of the roll-out of renewable power sources, 38 percent said it should happen “much faster” and 49 percent “a bit faster,” whereas only 13 percent said things are happening too fast.

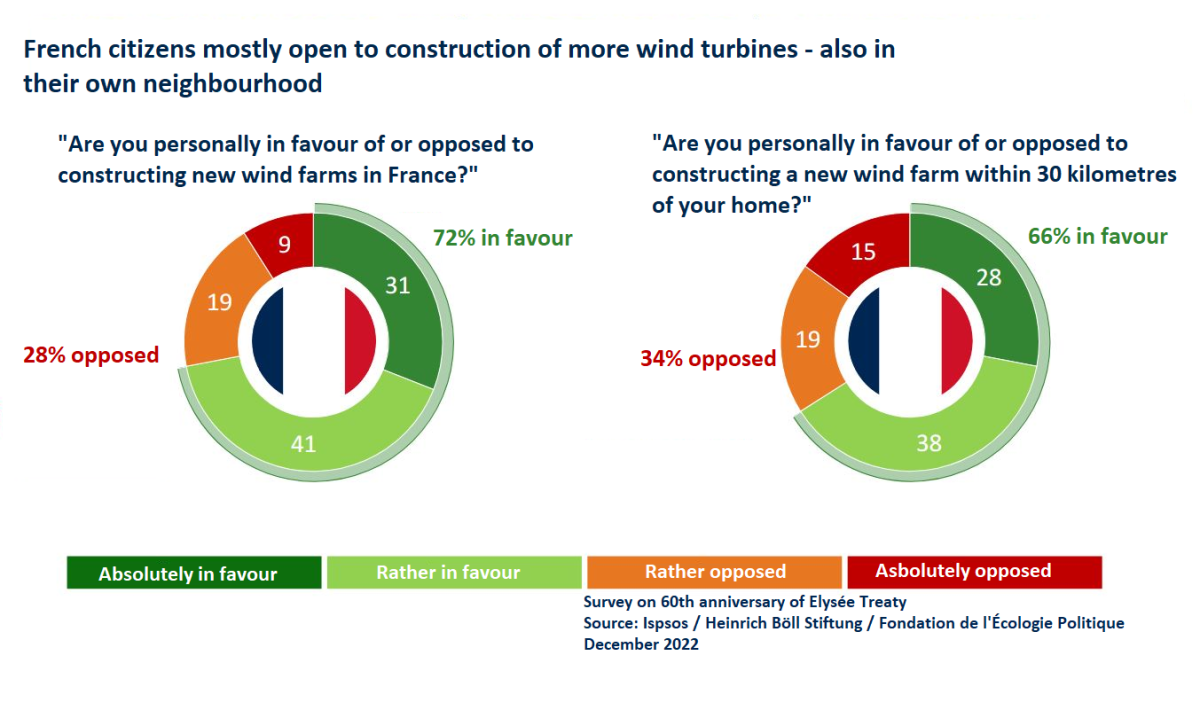

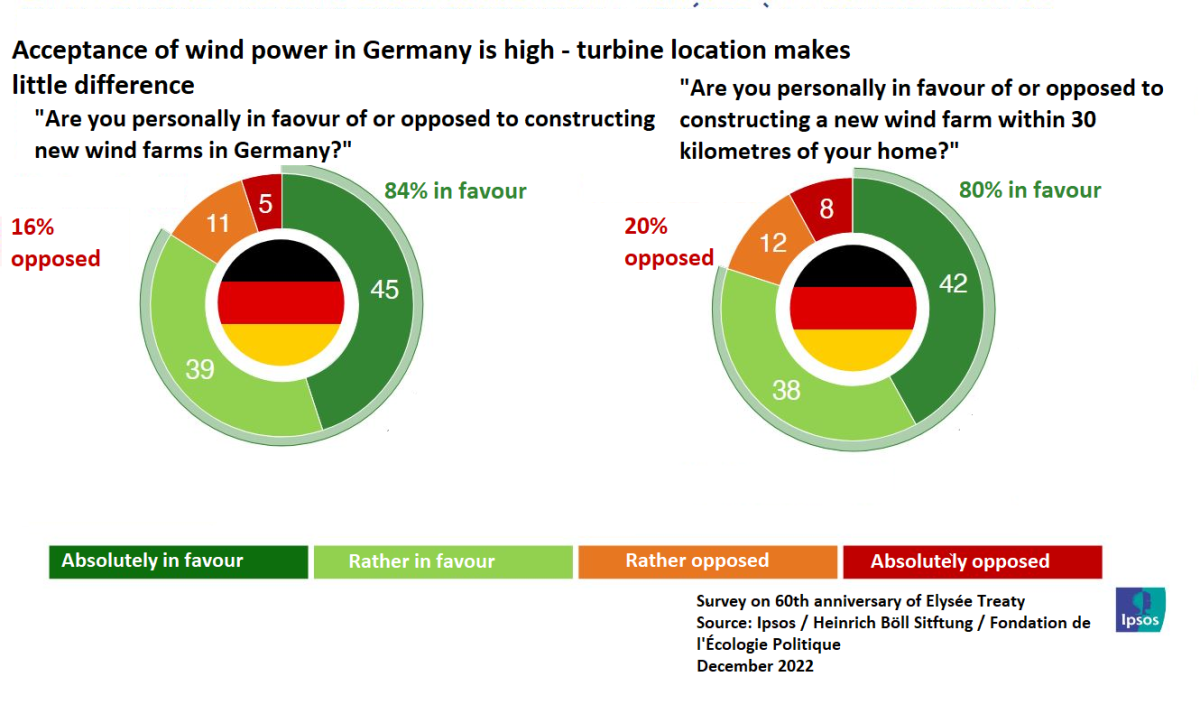

The bi-national survey by the Böll Foundation and the Ecological Policy Foundation revealed that the Germans consistently favoured renewables expansion more than the French. Sixty-eight percent of Germans said the ecological transformation was a priority compared to only 49 percent in France. The same survey showed that the difference between the countries was smaller regarding nuclear power, of which 37 percent in France and 27 percent in Germany said a relaunch would be among their priorities in the transition. However, in France, support for new wind turbines was also high. Although the technology is among the more controversial forms of renewable power generation, it was welcomed by 72 percent in France. Sixty-six percent were also happy if the wind farm would be built close to their homes. In Germany, the figures were 84 percent and 80 percent, respectively.

6. Which groups are pro and anti-climate action?

Both France and Germany have seen a rise in pro-climate movements which are demanding more resolute action on climate, as is the case across much of the rest of the world. Many environmental NGOs in Germany have been vocal proponents of stronger emissions reduction and other sustainability measures for decades. Most NGOs, many of which are active at the regional level and have strong ties to the anti-nuclear movement of the 1970s, have made climate action a cornerstone of their campaigning actions. Successful litigation undertaken by environmental groups led to a court ruling in Germany which triggered the country’s ambitious 2045 climate neutrality target. A highly centralised structure is considered a reason for a high degree of institutionalisation and comparatively weak social entrenchment of environmental groups in France, although this began to change in the 1990s. Many French NGOs have also made climate change a priority for their activities and have led legal initiatives to push the government to take more resolute action.

The Fridays for Future youth protest movement, which has spearheaded calls for stronger climate action in recent years, has made a notable impact in both countries. However, the protest group’s own climate strike statistics suggest a much higher level of engagement in Germany. Between November 2018 and March 2023, Fridays for Future counted 476 climate strikes in France, compared to 1,951 in Germany.

More recently, climate activist groups engaging in more disruptive protest tactics have made an impact in Germany and France alike. The activities of the Letzte Generation (Last Generation) movement in Germany and its French counterpart Soulevement de la Terre (Uprising of the Earth) have caused controversy among citizens, even if these share concerns about a lack of action on climate change. In Germany, members of government – including the Green Party – have criticised some activities of the Letzte Generation, while the organisation is still allowed to operate. The French government banned Soulevement de la Terre in mid-2023, arguing that the group’s actions amounted to violence.

At the same time, both countries have also seen a rise in marked rejection of specific climate policies, and a tendency by political parties, especially from the extreme left and right wing of the spectrum, to capitalise on fears and insecurities associated with emissions reduction efforts.

In France, such dissatisfaction became highly visible in 2018 when the government tried to raise the carbon tax against a backdrop of rising fuel prices, presented as essential to meet its climate commitments. Rural and semi-urban areas lacking strong public transportation would have been hardest hit by the cost increase. An online petition quickly led to long lasting and violent mass demonstrations under the ‘gilets jaunes’ (‘yellow vests’– a reference to the participants’ dress code of high-visibility vests) movement. The movement was a coalition formed by opposite political extremes (both right and left). As a result of widespread protests across France, the carbon tax was not increased in 2019 for the first time since its creation in 2014, nor was it raised in 2020. The movement pushed government to launch a ‘great national debate’ on public concerns about the cost of sustainability measures, the adoption of a 'Citizens' Convention for Climate’, the creation in April 2019 of an Ecological Defense Council (restricted council of ministers on those issues), and negotiations about a redistributive tax meant to ensure poorer citizens are not disproportionately hard-hit. Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right party Rassemblement National, has repeatedly appealed to yellow vest members, styling herself as the voice of those resisting climate policies. Indeed, most yellow vest adherents do sympathise with Le Pen’s party, at least according to a 2022 analysis.

In Germany, the far-right party AfD (Alternative for Germany) is the main platform for rejection of climate action. While Germany did not see a protest movement akin to the French yellow vests, the impact of protests in the neighbouring country has been felt also in the German debate, with scientists and government members warning against the repercussions for climate action from a large-scale protest movement. The AfD has actively supported public protest against consumption reduction measures in the energy crisis and has also vocally rejected other energy- and climate-related policies, such as the country’s coal phase-out, the shift to electric mobility or the energy transition in the heating sector.

Helene Miard-Delacroix, political scientist at the Sorbonne University in Paris, said that views from citizens affiliating themselves with right-wing parties showed striking similarities in both countries, creating a “false sense of harmony.” Even though this may suggest that some form of meaningful cooperation could be developed, the prospects of this looked rather slim for the time being, Delacroix stated on the publication of the bi-national survey of the Böll Foundation and the Ecologic Policy Foundation.