Extreme weather forces unprepared Europe to focus on climate adaptation

[This article is part of a larger package on climate change adaptation. Read the full CLEW dossier Ill-equipped Europe braces for impact of rising temperatures.]

Mention climate change and the need to adapt to the increasing number and ferocity of extreme weather events, and most people mention drought in East Africa or flooding in low-lying Bangladesh. The region experiencing the highest rises in temperatures because of climate change is, however, Europe. The impacts of this warming were fully felt in 2022, as various countries suffered the worst drought and highest temperatures on record. The trend continued in 2023 as the continent experienced a winter heatwave. The warm temperatures led many to rue the lack of snow in lower lying ski resorts, but more problematic is the impact this will have on freshwater supplies later this year.

Europe, like countries everywhere, must act now to adapt to climate change. Progress is being made, but it needs to be faster and more homogenous across the EU if all of its citizens are to be protected against the worst impacts of a warming world.

"Adaptation is not only about adapting to climate change, but also about empowering the population to be more resilient,” says Carolina Cecilio from climate think tank. E3G. “The pandemic put adaptation on pause, but all the EU institutions are aware, particularly after this summer, that the impacts of climate change are only going to get worse if significant action is not taken.”

Adapting to climate change will not be easy. The goalposts are moving all the time as the world continues to warm, aggravating the impacts. "Adaptation is always a moving target,” says Angelika Tamasova from the European Environment Agency (EEA). “The planet is getting warmer, and the adaptation measures planned and implemented now might not be sufficient in the future."

Increasing support by EU institutions, national governments, and the private sector will all be key to ensuring that Europe is in the best possible shape to deal with the challenges posed by a warming world.

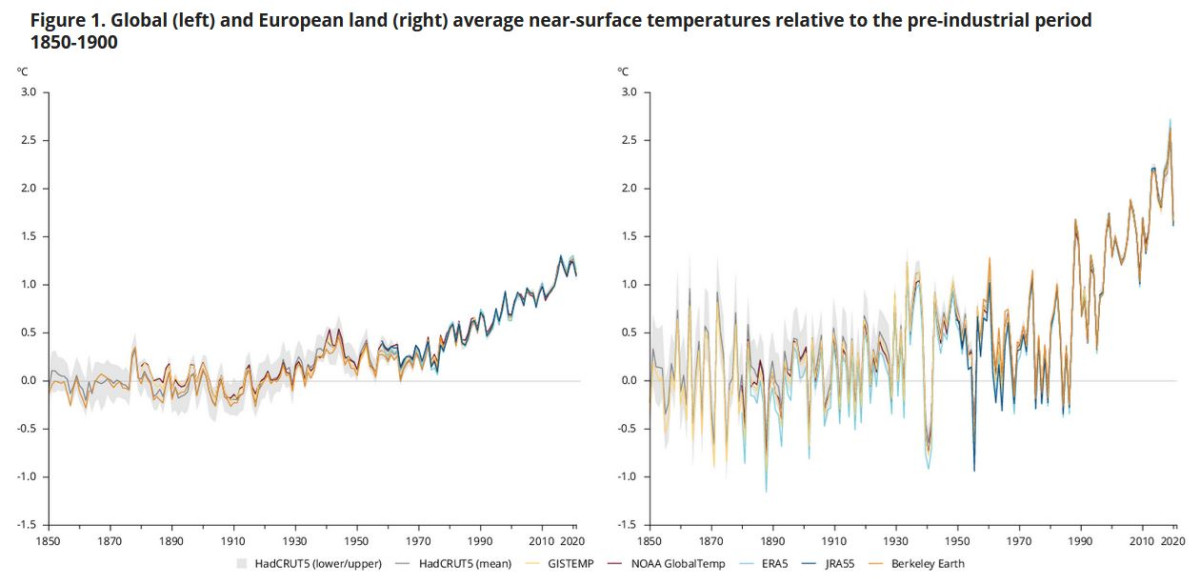

“Temperatures in Europe have increased at more than twice the global average over the past 30 years – the highest of any continent in the world,” according to the World Meteorological Organization. “As the warming trend continues, exceptional heat, wildfires, floods and other climate change impacts will affect society, economies and ecosystems.”

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, global leaders agreed to try to hold warming at 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. But European land temperatures have already increased almost 2°C, with no end in sight. “Projections from the [World Climate Research Programme] suggest that temperatures across European land areas will continue to increase throughout this century at a higher rate than the global average,” says the European Environment Agency (EEA).

Until recently, adaptation was the poor cousin compared to climate mitigation. Climate action in the EU was almost fully focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, rather than on helping people, businesses, towns or cities prepare for more frequent and more intense extreme weather events. Adaptation measures were left to member states with little coordination at an EU level. This approach has, however, changed in recent years.

"We need to do mitigation as reaching climate neutrality is the way to avoid a serious future catastrophe,” says the EEA’s Tamasova. “Without successful mitigation, at some point we might fail to deliver on adaptation. It is, therefore, understandable why the discussion is centred around reducing greenhouse gas emissions. On the other hand, we are already impacted by climate change and so we need ambitious adaptation as well."

"Mitigation is easier as it has clear targets,” says E3G’s Cecilio. “Identifying key emitters, be it countries or sectors, is more straightforward, and so it is easier to set clear goals and legislation to deliver on them.”

Furthermore, the benefits of investing in adaptation measures, such as flood defences, may not be seen for 10 to 15 years. Such timeframes are well beyond electoral terms, meaning adaptation is generally not seen as a vote winner or a political priority.

There has also been the long-standing perception that a focus on adaptation measures would be to the detriment of mitigation, and would prove that efforts to cut emissions have failed. Yet, such thinking clearly does not hold water. Even if the world were to stop emitting greenhouse gas emissions tomorrow, adaptation would remain a necessity, given the amount of warming already underway.

Even if climate adaptation has not received the same attention as mitigation in the EU, the region is nonetheless leading the world in this area.

In 2013, the EU adapted its first climate adaptation strategy. On a global level, the 2015 Paris Agreement gave equal weight to adaptation and mitigation. Since then, the EU has adopted its Green Deal, Climate Law and, in 2021, a new adaptation strategy. The Climate Law focuses on mitigation, but also on increasing resilience in the EU and here adaptation will have a key role to play. “The European Climate Law brought a huge change by making adaptation mandatory,” says Tamasova.

As the EEA highlights in a December 2022 report, all EU member states have now adopted national adaptation strategies in some form or other. Since the adoption of the European Climate Law in 2021, EU member states are increasingly making use of national climate laws to mainstream climate adaptation and enforce strategies and plans, and are slowly shifting away from voluntary adaptation measures. However, most adaptation plans still come into some criticism for continuing to be “soft policies without legally binding commitments,” says the EEA.

There remains considerable variability across the region in terms of exactly how adaptation is addressed, but a common way for member states to tackle climate adaptation is to mainstream it into national and sectoral planning processes. In concrete terms, this means addressing heatwaves, flooding, drought or other climate extremes in policy making related to various sectors including agriculture and forestry, maritime, inland waters and coastal management, energy, disaster risk prevention and management, urban planning, research, biodiversity, migration and mobility, health and the environment. Examples of this approach in practice are varied and widespread. Here is a flavour of what’s happening across Europe:

Agriculture: Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region boasts more than 84,000 farms covering around 1 million hectares invested. A third of these farms include irrigated land. Water scarcity and droughts are already increasing in the region, and climate change is expected to worsen the situation, significantly reducing the amount of water available for agriculture. In 2019, the region introduced Irrinet, a web service advising farmers on efficient water management.

Urban planning: Barcelona is Spain’s second most populated city with 1.6 million inhabitants. The city is already suffering from many climate change impacts common to the Mediterranean region, including rising temperatures and heatwaves, reduced water availability, drought, and increased flooding due to irregular and torrential rain. The city’s Barcelona Nature Plan 2030 sets out to increase green spaces and tree coverage to temper the climate conditions, and help prevent local flooding.

Transport: Sea level rise and more extreme storms and cloudbursts are exacerbating the flooding risk for the underground in the Danish capital, Copenhagen. Following a climate change adaptation strategyfrom the city’s metro company Metroselskabet, work has been carried out to ensure runoff water does not flood underground stations, and floodgates, pumps and waterproof walls have been installed. The measures are aimed at keeping the metro running during extreme weather events, and keeping passengers safe.

Adaptation by its very nature has to largely be implemented locally, as E3G’s Cecilio says, with even different parts of the same country potentially facing “very different challenges”. The EU faces a plethora of risks from climate change. “Heatwaves, droughts, floods, heavy precipitation and changing temperatures are the most reported climate-related hazards and highly relevant for (almost) all countries,” says the EEA. Even where they face the same challenges, the political and financial support for adaptation can be different depending on the member state in question. But overall, cities and municipalities often struggle to access the level of funding they need to carry out adaptation measures.

“There is a large and chronic underspend on adaptation in cities,” says Stella Whittaker, a researcher at Copenhagen Business School, who has studied adaptation financing in the Danish capital and is now examining the issue in London and Singapore. “Cities are making valiant attempts to find new ways of financing the climate change adaptation needs in their cities, but these costs are so large that this is an almost impossible task for them to tackle alone.”

There is EU funding for adaptation measures from a multitude of programmes, including Interreg, the Life programme and Horizon Europe, the EU research and innovation funding programme. Particularly promising is the finance pledged under the EU Mission: Adaptation to Climate Change initiative launched under Horizon Europe in 2021. It aims to help at least 150 European regions and communities increase their climate resilience by 2030. Historically, though, many smaller municipalities have found it difficult to access EU funding, which often relies on completing long, complex proposals. To help local authorities find their way through this quagmire, the European Committee of the Regions published a Green Deal Handbook focused on climate adaptation in 2022.

Further complicating the matter, it’s often difficult to track exactly what funding is spent on adaptation. Nature restoration projects, for example, can also help places cope better with increasingly heavy downpours, but may not be reported as climate change adaptation. Indeed, there is no standardised EU-wide reporting for adaptation funding. EU member states reported on their national adaptation actions for the first time in 2021, but reporting on financing was only a marginal part of the exercise. They will report back again to the European Commission by 15 March 2023.

The EEA stresses that both public and private sector engagement is necessary to speed up climate adaptation. The private sector is “essential” for implementing adaptation measures and “can be a source of finance for adaptation,” says the agency. Public-private partnerships can also be a useful way to advance action, it states, and notes that government schemes “rewarding innovation” are a good way of highlighting best practice.

Copenhagen Business School’s Whittaker believes the “the only option open to governments” in terms of financing climate adaptation measures is to leverage private capital. “Innovation is needed not only in technology but also in approaches to financing and investment” to make it easier for cities to access the “large untapped potential” from private investors,” she says.

Researchers at Imperial College London have suggested creating a new global asset class of adaptation bonds, dedicated to adaptation and resilience projects. They cite the success of the US municipal bond market in financing domestic infrastructure projects as proof that this solution could provide much needed additional funding.

How much private sector financing actually goes into climate adaptation today is unclear as there is no pan-European demand for such reporting.

What happens next?

2023 will be an important year for climate adaptation in Europe. Under the EU Climate Law, the European Commission is bound to publish a progress report on adaptation and mitigation measures. Likely to be launched in October, the report, which will be updated every five years, will create a baseline for adaptation action. Following the publication of this report, the Commission has the power to issue recommendations to member states if their measures are deemed to be inconsistent with ensuring progress on adaptation. Legislation pushing member states to go further and faster on climate adaption will also come through various measures agreed under the auspices of the Green Deal.

The Nature Restoration Law currently being worked on by the Commission and the European Parliament with EU member states is “a step in this direction,” says E3G’s Cecilio. She believes, however, that more will still need to be done to push adaptation in the EU and introduce clear targets for its implementation: "At some point the EU will need to come up with a strategy like Fit for 55 for adaptation.”