Military has understood strategic advantages of low-carbon technology – security researcher

Clean Energy Wire: Russia’s war on Ukraine and the return of Donald Trump to the White House have led to a drastic shift in the perception of security policies across Europe, as the region rushes to make good on decades of reduced defence spending and make its militaries more capable. As the EU’s biggest economy, Germany has spearheaded this race by announcing its ambition to build the bloc’s strongest army by the 2030s and by effectively removing spending limits on defence. Will the upcoming spending boost for the military in Germany and Europe inevitably lead to higher emissions?

Ole Adolphsen: More emissions are not necessarily locked in now, but it’s generally true that higher defence spending and a bigger military tend to come with higher emissions. But there is no direct link between increased military budgets and a rising greenhouse gas output.

For Germany’s military, the Bundeswehr, you could already see that the trend of falling emissions was reversed well before the so-called ‘Zeitenwende’ strategic policy change in 2022 in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when the government announced it would devote much more resources towards strengthening the Bundeswehr’s capabilities.

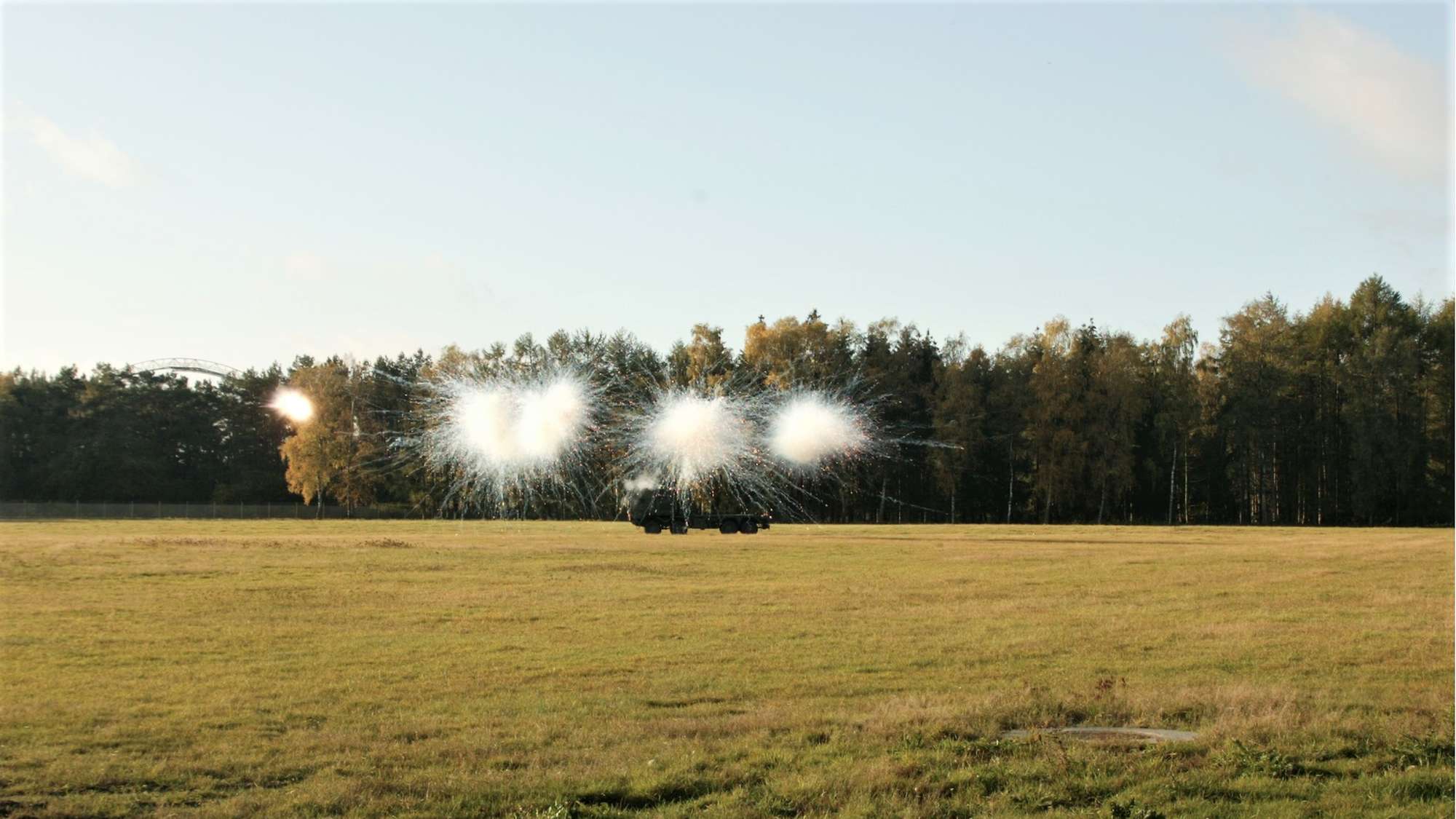

Exploding rockets and heavy-duty vehicles come to mind when thinking of military emissions – what are the main sources of greenhouse gases caused by the army?

Military emissions in general don’t differ greatly from civilian emissions. There are two broad categories to look at: stationary emissions and mobile emissions. The first category mainly concerns buildings and other facilities, for which the greatest emissions factor for the Bundeswehr is heating. Mobile emissions, on the other hand, concern everything that allows the army to move troops or equipment, meaning land-based vehicles, ships and, above all, aeroplanes.

While most armies have a fleet of regular passenger cars or transport vehicles, there, of course, are also very specialised military vehicles with niche uses. These on average tend to have higher emissions.

Does this mean that the tools for decarbonising the military do not even differ that much from those that the rest of society has, for example heat pumps or electric cars?

In principle, yes, but the specific activities of the military make things a little more complicated. Aeroplanes are one of the biggest emitters in the military and can account for as much as half of an army’s total emissions. Land-based equipment does not only become more emissions-intensive the more specialised it is for military purposes but also the closer it is to active battle zones.

It’s now a widespread understanding that renewable energies in fact offer a range of strategic advantages for the military.

Operating and maintaining heavy machinery on duty with low-carbon technology faces many technical and logistical challenges that are yet to be resolved. Concepts for electric tanks, for example, have largely been shelved because the energy density of batteries simply cannot yet match that of fossil fuels, which slows operations down due to refuelling times and other aspects. Synthetic fuels offer a possible solution here, especially for aeroplanes and other airborne vehicles.

What do you think of Rheinmetall’s recent announcement that it will launch its own hydrogen production infrastructure?

It’s not yet clear where and in which applications hydrogen can play a decisive role. Not only does it look set to remain a scarce resource for the foreseeable future, it also comes with a raft of technical challenges, for example cooling, that pose challenges for military use. But more broadly, synthetic fuels offer a wide range of possible uses that are certainly going to be explored further.

Would you agree with the statement that decarbonisation is contradicting military capability?

Not really. There’s a difference between what is technically or theoretically possible and what the political consensus or approach allows to happen. On the one hand, there has been a major shift in society. The environmental and peace movements of the 20th century were parallel developments that generally rejected militarisation – a posture mirrored by the military’s relative disregard of climate change or other environmental factors. This contradiction has dissolved gradually since the end of the Cold War, illustrated, for example, by the Green Defence concepts.

Russia’s war on Ukraine then fully showed the risks of Europe’s fossil fuel dependence and the role that low-carbon technology can play in national security. It’s now a widespread understanding that renewable energies in fact offer a range of strategic advantages for the military. Moreover, technological advancements and breakthroughs today are mostly expected in electric applications – and the military aims to take part in this race for cutting-edge technology. In addition, low-carbon technologies also offer a range of tactical advantages, including the lower heat and noise footprint of electric vehicles that make them more difficult to detect.

The Paris Agreement stipulates that many countries around the world work towards achieving net-zero emissions by mid-century. How much has the military been considered in these plans and can one really expect net-zero armies by the middle of the century?

This is difficult to say – and the security sector is certainly not the only one where many questions remain unanswered. Under the UNFCCC [United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change], military emissions reporting has been possible but wholly inadequate.

Hard-to-abate sectors will likely continue to emit beyond the target date – and these emissions will then have to be offset. So, in principle, the military sector could be covered by debates about hard-to-abate emissions – but we lack relevant data on both national and international level.

What is needed is better projections for the kind of military emissions that should be addressed, in what time frame, and which emissions are too costly to mitigate – a political question in the last instance. There are very few explicit net-zero targets for concrete military activities or intermediate steps or a roadmap for how to achieve all this.

Critics say that military emissions are not properly accounted for in general and that a large part happens undetected or at least never shows up in statistics. How serious would you say is the underreporting problem in the sector?

There is no blanket exception for military emissions under the UNFCCC, but there are blurry areas and a lack of reporting. Large parts of military emissions – especially if you consider relevant supply chains – do show up in national statistics but are not marked as military emissions. There is probably a portion that is not properly accounted for, but it is not this hidden class of emissions that threatens our climate targets all by itself.

However, at a global scale and when including all militaries, military emissions amount to a serious chunk of emissions. Reporting rules under the Paris Agreement that have now been expanded to most developing countries are our best chance to shed more light on this question.

Environmental activism and anti-military movements have long been associated in Germany – and helped the establishment of the Green Party in the 1980s. In the previous government, the Greens have been the most vocal coalition party when it comes to supporting Ukraine militarily and rearming Europe. At the same time, the far-right AfD has presented itself as an appeaser towards Russia, but has little regard for environmental policies. Has defence policy become part of climate action?

Military activities and warfare will always remain harmful to the environment. Green defence efforts in recent years, especially in Europe, rightly highlight the numerous co-benefits to integrate the military in climate plans as much as possible. What is true is that reducing the dependence on petrol exporters has been identified as a strategic advantage for the defence sector that aligns these goals to some extent.

Will the focus therefore fully shift to electric vehicles and away from fossil-based systems, as drones and other new equipment become widespread on the battlefield?

It is difficult to predict investment and purchase choices, as the development of new systems and the military’s inventory planning often take place in cycles spanning several decades. Small and innovative systems like drones are more likely to be developed fully electrically from the start, while large systems or heavy machinery, such as tanks, will be transformed at a much slower pace and potentially be upgraded to use non-fossil fuels only at a later stage. But saving fuel is not the primary motivation here.

Climate neutrality was made a key aim of Germany’s 500-billion-euro special fund alongside modernising the country’s infrastructure. The country has also changed its constitutional debt brake rule to allow theoretically unlimited borrowing for strengthening the military. What role do climate and energy play in this expected spending spree for the Bundeswehr?

The Bundeswehr has worked on climate action and energy transition aspects for a few years now and already adopted several strategies that guide its related activities. This includes the Sustainability and Climate Action Strategy, in which it outlines its contribution to national climate neutrality and its own net-zero targets. But there sure is a new impetus to the entire climate-security nexus that was triggered by geopolitical events in recent years that has not yet fully translated into concrete new approaches or strategies.

The EU’s climate branch has said that it will not interfere with security policy decisions on environmental grounds but that it rather aims to tap into so-called co-benefits for the climate from the bloc’s re-armament campaign. What in your opinion is the potential for positive spill-over effects for climate action?

The EU certainly aims to pursue different policy goals simultaneously and make use of synergies between security, climate and industrial policy where possible. It could make sense to use defence spending to support lead markets for green steel, for example. But it is not yet clear how this will play out.

NATO has tried for a while to strengthen the recognition of the climate-security nexus, starting with its Green Defence framework in 2014. In 2022, at a summit in Madrid, NATO then released its Climate Change and Security Impact Assessment – and also announced the ambitious goal of reaching net-zero emissions at least for its civilian structures.

It also runs a so-called centre for excellence for climate and security in Canada since 2024 and another one for energy security in Lithuania since 2012, which shows that there is a commitment to address these topics and exchange best practices among NATO members. And it has worked on a methodology for measuring military emissions that helps to better quantify the often complex greenhouse gas sourcing of national security sectors.