CLEW Guide – Poland stumbles through energy transition with uneven progress and political headwind

With its “CLEW Guide” series, the Clean Energy Wire newsroom and contributors from across Europe are providing journalists with a bird's-eye view of the climate-friendly transition from key countries and the bloc as a whole. You can also sign up to the weekly newsletter here to receive our "Dispatch from..." – weekly updates from Germany, France, Italy, Croatia, Poland and the EU on the need-to-know about the continent’s move to climate neutrality.

(With contributions by Wojciech Jakóbik)

Content:

Key background

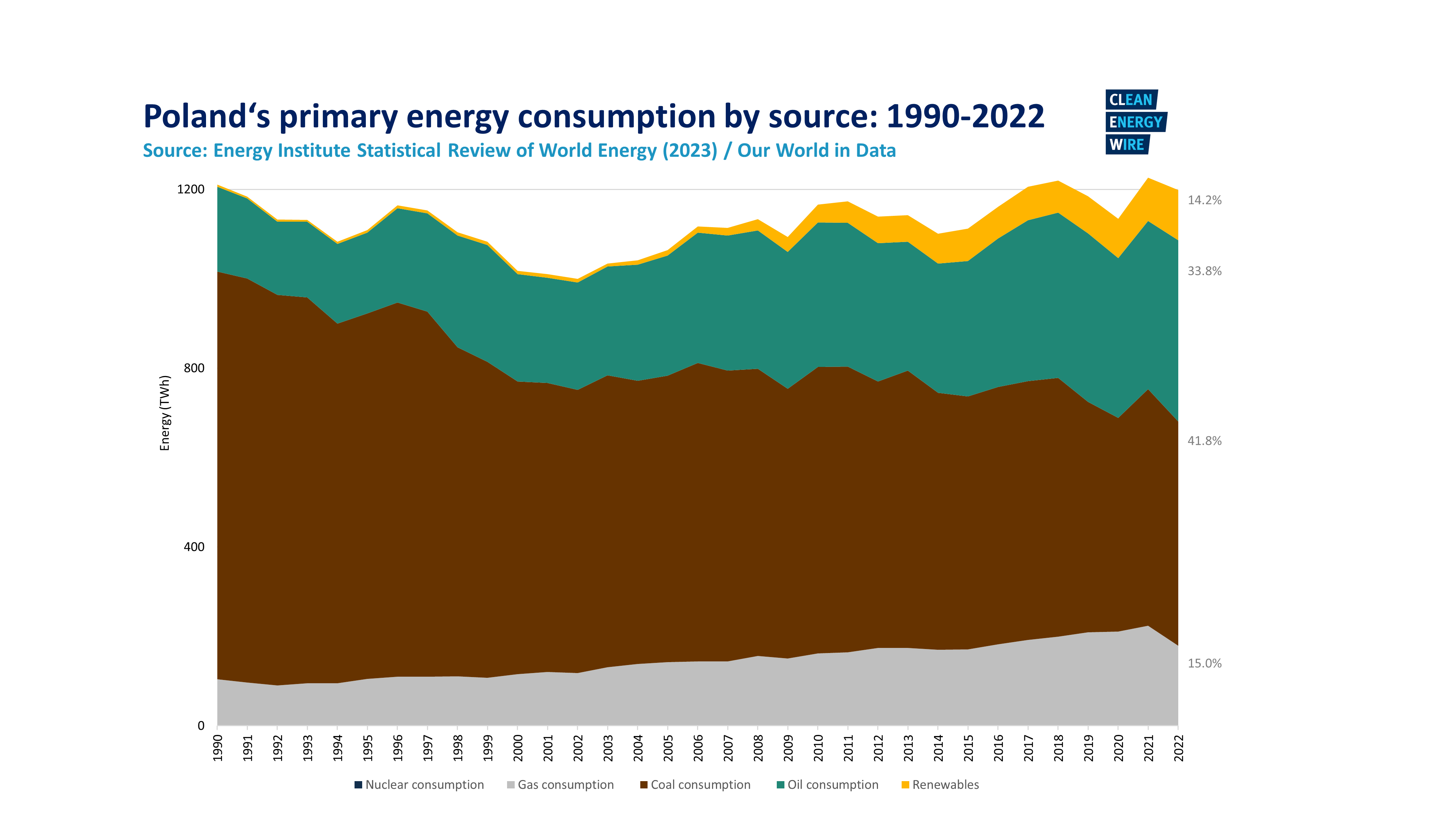

Over the past 35 years, Poland has risen from a developing, post-communist state to one of Europe's strongest economies and been integrated into NATO and the European Union. For years, domestic coal resources provided cheap and reliable energy. But that – together with a strong coal industry and labour unions – discouraged the transition to other sources of electricity.

Today, the cost of extraction makes domestic coal more expensive than imports, and the government is subsidising mines with billions of zlotys each year. At the same time, the cost of the EU’s emission trading scheme (ETS) adds to electricity bills, which burdens the economy as Poland has the highest carbon intensity in the EU. In recent years, however, Poland lowered the share of coal in its electricity mix, from over 80 percent in 2018 to 52.8 percent in 2025.

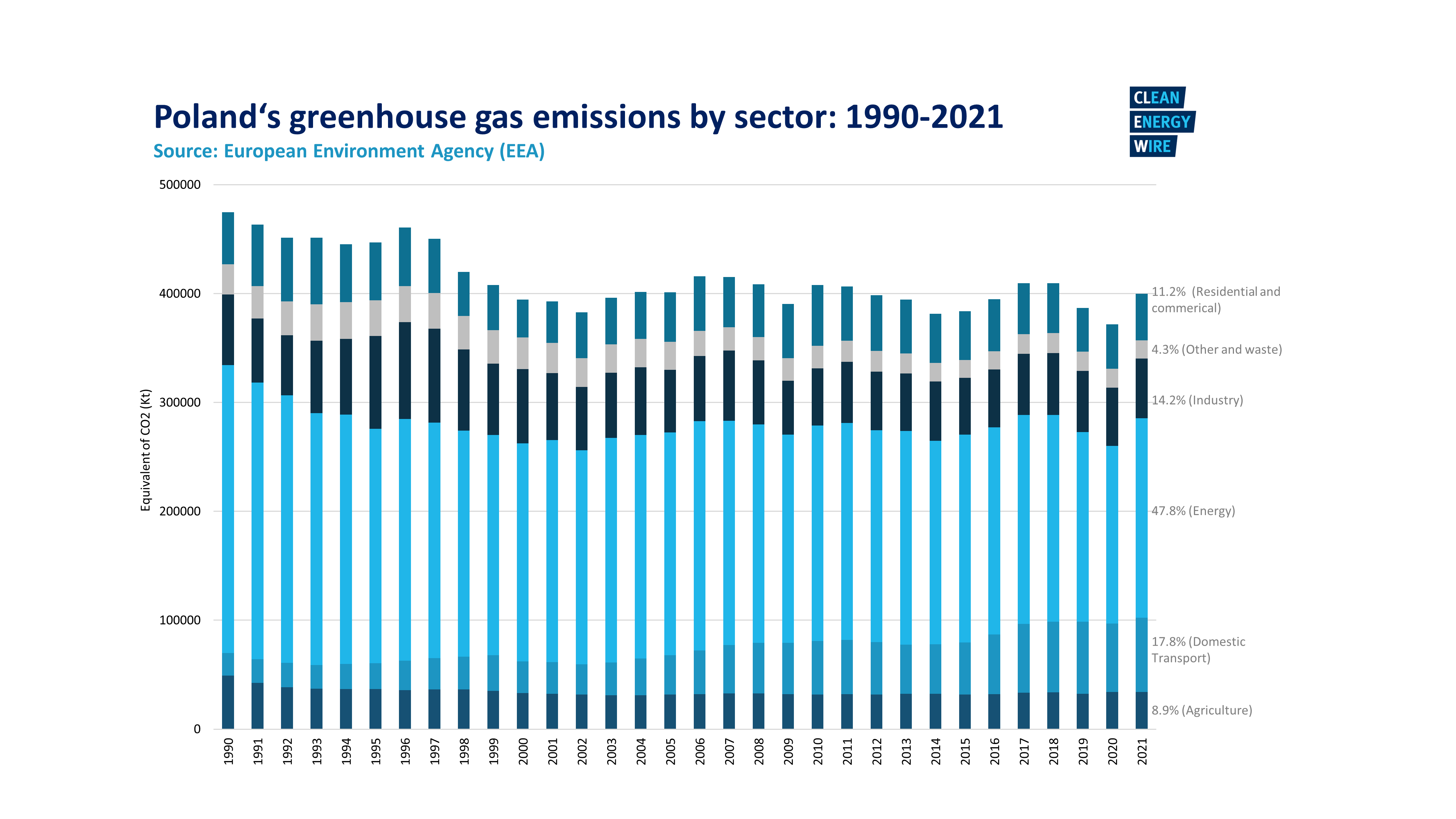

Poland was responsible for just under 11 percent of the EU’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2023. Emissions in the country have fallen over 30 percent since peaking in the 1980s. Most of the reductions occurred in the 1990s during the fall of communism and the shift away from a planned economy. Poland's current target under EU rules for sectors like transport, buildings and agriculture is a 17.7 percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 2005 –far less than other countries like Germany or Denmark (50%). Poland's total emissions in 2023 were 9 percent below 2005 levels.

The current government of prime minister Donald Tusk consists of a broad coalition from centre left to centre right. It took power in 2023 after defeating the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) and promised a faster energy transition. However, during almost two years since taking power, it has been slow in delivering key legislation. Their efforts were further hindered when PiS-backed Karol Nawrocki won the presidential election in 2025. As president, the right-wing former historian has the power to veto any bill, potentially blocking any and all legislative change, a power he has so far used at a much higher rate than his predecessor. Nawrocki, a newcomer in politics, strongly opposed the EU Green Deal during his campaign.

Poland faces various ecological issues, some connected to fossil fuels and climate change. Both droughts and floods have intensified in recent years. Air pollution is a major public health concern, fuelled by both cars and furnaces, as no other EU country uses nearly as much coal for heating.

Major transition stories

Uneven energy transition. Poland has managed to significantly reduce the share of coal in electricity production in the last decade, but the buildup of other sources of energy has been out of balance. The slow but steady development of wind farms was almost reduced to zero for years after 2016 due to unfavourable legislation. Solar power played no role until around 2020, when a boom in photovoltaics started and development quickly outpaced onshore wind. This has led to overproduction of energy on sunny summer days and leaves the country more reliant on coal in winter. In 2025, construction started on the first offshore wind farms that will come online in the coming years.

Lack of strategy. Poland’s most recent strategic document on the energy transition is from 2021, but as experts have said, it was already out of date the moment it was adopted. For example, Poland already has twice as much solar PV as the strategy envisioned for 2040. Despite that, Donald Tusk’s government has so far not updated the corresponding energy policy plans. Poland is the last country to submit its updated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) to the EU, which prompted the European Commission to launch a legal action against Warsaw. Poland is also the only country in the EU that does not have an official date for ending the use of coal.

Political divide over climate and energy transition. Centre-right and far-right parties in Poland have been highly critical of EU climate policy (and sometimes going into climate denialism), while centrists, liberals, and the left propose a faster energy transition and more environmental protection. One of the few issues that enjoys political consensus is developing nuclear energy.

Just transition plans have been drawn up for coal regions, but not all of them will receive EU funding. Eastern Wielkopolska, which has just one remaining lignite plant, has been fairly successful in implementing a just transition. However, other coal regions have greater numbers of workers in the sector. In the town of Bełchatów, the largest lignite mine and power plant in Europe dominates the local economy – and its closure will pose a great challenge. The lignite mine in the Turów region was not approved for support, as coal extraction is planned to continue until 2044. In December 2025, a bill that facilitates closures of a number of coal mines and introduces compensation for miners was adopted and later signed by the president.

- In October 2025, the Polish government approved a draft bill that facilitates coal mine closures and introduces compensation for miners. It is likely, however, to be vetoed by president Nawrocki, who is a staunch supporter of coal.

Getting rid of Russian fossil fuels. Poland has managed to diversify its gas, oil, and coal supplies after heavily relying on imports from Russia. Gas imports – which are set to increase with new gas power plants being built – come mainly through the LNG terminal in Świnoujście (with gas from the USA, Qatar, and others) and via the Baltic Pipe gas pipeline from Norway.

Polish smog. Poland has struggled with fixing its air quality problem, as the smog is causing around 40,000 premature deaths each year. Only Warsaw and Kraków have implemented Clean Transport Zones, and the share of electric vehicles in the car market is far behind Western Europe. A "Clean Air" programme, with subsidies for replacing old coal furnaces, has faced difficulties in 2025. Implementation of the EU’s new emissions trading scheme (ETS 2) is a major concern, as it will put a heavy financial burden on some of the poorest households that are still using coal for heating.

Going nuclear. According to government plans, Poland is to build two nuclear power plants with a total installed capacity of 6 to 9 gigawatts. Previous attempts to build nuclear reactors, going as far back as the 1970s, have not been successful. The current project for the first plant, with the US firm Westinghouse as a technological partner, is at the advanced planning stages and construction on the Baltic coast is expected to start in 2028. While 2033 was the original planned opening date, 2035 at the earliest now seems more realistic. Polish state oil company Orlen is planning to build two Small Modular Reactor (SMR) units by 2035.

Hi-speed ambitions. Poland has plans to develop a high-speed rail network as part of the Centralny Port Komunikacyjny (CPK) project, along with a big airport located between Warsaw and Łódź. It will also include Local Mobility Hubs (LMHs), serving as multi-use railway stations. The first high-speed trains should start operation in the early 2030s.

Battery powerhouse. In April 2023, Poland overtook the US as the country with the second largest lithium-ion battery production capacity in the world. According to a 2025 report by New AutoMotive, “Poland has become one of Europe’s most important battery manufacturing centres” in terms of both production and recycling. However, “challenges remain” if it is to keep that position.

Sector overview

Energy

- Responsible for 46.9 percent of Poland's total GHG emissions in 2023 (51.1% in 2022).

In 2025, coal was the main source of electricity (52.8 percent). It remained the largest proportion by far in the EU, despite the significant drop from 70 percent in 2022. Wind and solar’s joint share rose to 25.4 percent, and renewables in total reached almost 31.2 percent.

- The country’s energy sector is dominated by large, state-owned or partially state-owned companies, like the oil corporation Orlen or Polska Grupa Energetyczna (PGE), an energy company that owns coal plants and mines. The lignite plant PGE Bełchatów is the EU's highest emitting power plant, but now it has a plan to gradually close down by 2036 (with a 77% reduction until 2030).

- Poland plans a gradual coal phase-out, replacing it with a mix of renewables and nuclear generation. New fossil gas plants are set to be built too, but some plans have been revised after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- In 2021, Poland adopted the Energy policy of Poland until 2040 (PEP2040) programme with the following targets: 32 percent of renewables in electricity generation and no more than 56 percent of power from coal by 2030, and the first nuclear power plant starting operation in 2033.

A forecast can be found in a draft update of Poland’s National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). In the ‘active transformation’ scenario of the plan, by 2030 Poland would reduce it CO2 emissions by 53.9 percent (compared to 1990) and renewables reach a 51.6-percent share in electricity production, with “gas playing the role of a bridge fuel”.

- According to electric grid operator Polskie Sieci Elektroenergetyczne, the operational capacity of photovoltaic panels and wind farms reached a combined 34 GW in June 2025, of which around 23 GW are solar PV.

Industry

- Responsible for 14.6 percent of total GHG emissions in 2023 (14.8 in 2021)

- Over 21 percent of the total workforce is employed in the industrial sector.

- Energy intensity of industry (per GDP unit) is above the EU average, but companies are increasingly looking to improve efficiency and use zero-carbon energy, both in the form of renewables and small nuclear reactors.

- CO2-intensive industries in Poland are comprised of both private domestic, international companies (like ArcelorMittal), and partially state-owned companies (like Orlen and Grupa Azoty). The sectors of Polish industry which emit most CO2 are cement, oil and coke as well as chemicals and fertiliser production.

- Since 2022, energy-intensive industries have struggled with big increases in electricity and gas prices. The high carbon intensity of the power sector is not only driving up prices, but also increasingly threatening business as more and more clients are looking not just at price, but also at the carbon footprint.

- The industrial sector increasingly looking to invest in its own sources of electricity, from renewables to batteries, and even small modular reactors (SMRs).

Buildings and construction

- Responsible for 11.5 percent of total GHG emissions in 2023.

- Solid fuels (coal, wood) and district heating (mainly coal plants) dominate in the heating sector, but gas boiler use has increased markedly in recent years, now heating one quarter of all buildings (according to incomplete government data).

- The energy crisis led to a boom in heat-pump sales, but that proved temporary. With elevated electricity prices, biomass (in particular wood pellet) boilers have become a more popular replacement for old coal furnaces.

- Until recently, Poles accounted for as much as 87 percent of the total amount of coal burned by EU households.

- Almost two-thirds of buildings in Poland are characterised by low energy efficiency.

- The current government targets are: phase-out coal in city homes by 2030 and outside cities by 2040, with all heating covered by “low emission sources” or district heating by 2040 (experts point out that this could be achieved much sooner). The building renovation strategy sets a target of renovating and insulating 236,000 buildings per year between 2020-2030, with numbers increasing in the coming decades.

- Polish cities have some of the worst air quality levels in Europe with buildings (mainly solid fuels furnaces) being the biggest contributor to fine particulate pollution.

- Over 40 billion PLN (€9.4 billion) were contracted for household heating source replacement as part of the government's “Clean Air”. The programme was suspended in November 2024 citing “irregularities” and relaunched at the end of March 2025. But the first months of the new version show that it has lost much of its popularity due to cases of fraud and what NGOs characterise as government mismanagement.

Mobility

- Domestic transport was responsible for 21.6 percent of total GHG emissions in 2023 and is the only sector that saw an emissions increase between 1990 and 2023.

- In 2019, the government adopted the Sustainable Transport Development Strategy until 2030. It assumes an eight percent rise in CO2 emissions from transport by 2030 (compared to 2017) and has no specific target for a number of electric vehicles (EVs) on Poland’s roads. In a draft update to Poland’s National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), the government led by prime minister Donald Tusk concluded that it would be “impossible” for Poland to meet the EU’s target of 29 percent of renewable share in the transport sector – it projects a 17.7 percent share by 2030.

- As of September 2025, Poland has 202,593 electric cars, including almost 102,567 all-electric BEVs, with the market share growing. The country has just under 11,000 charging points. According to Eurostat data, in 2023, Poland had the EU’s joint-lowest share of fully electric cars.

- A new electric car subsidy program was launched in February. Worth PLN 1.6 billion (€380 million), the program provides subsidies of up to PLN 40 000 (€9,540) for the purchase of an electric car (if all conditions are met). The funds come from the EU's Recovery and Resilience Fund.

- Poland is the EU’s leader in road freight, but the industry could be left out from the European market without a transition to zero-emission trucks.

- Poland is Europe's biggest producer of lithium-ion batteries, and second-largest in the world (after China).

Agriculture

- Responsible for 10.85 percent of total GHG emissions in 2023 (9.5% in 2021), mostly in the form of nitrous oxide and methane (caused in around equal parts [40%] by soil related emissions and direct livestock emissions).

- There is no governmental emissions reduction target; the government only points to EU-wide targets for 2030 and 2050.

- The government sees biogas as an important route to the development of a circular economy in rural areas and providing low-carbon energy.

- The effects of climate change, especially drought, are already impacting Polish agriculture.

Land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF)

- Forests and other areas remain a net carbon sink and removed 32.7 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents in 2023 (corresponding to 10.3 percent of total emissions).

- Around 30 percent of Poland is covered by forest (a number similar to countries like France or Germany), around 80 percent of which are state owned and managed by the State Forests National Forest Holding company. In 2023, State Forest had a record income of 11.2 billion PLN (~€2.6 bln) from timber sales. In recent years, the company has come under criticism from NGOs and private citizens for a number of issues, from lack of transparency to logging in old-growth forests. The Tusk government is working on reforming the institution and protecting 20 percent of forest.

- The level of CO2 removal capacity by forests has been decreasing over the last decade, with a sharp fall in recent years (from over 40 million tonnes to just over 20 million tonnes). According to Poland's emissions report, the main reasons are due to the long-term effects of disasters like long-term drought and storms with strong wind causing trees to fall. Timber harvesting is also on the rise.

- The former United Right coalition government has been pointing to forest sequestration as a climate solution, including during COP24 in Poland, but sequestration levels have been falling and, in 2021, it amounted to only 52 percent of Poland’s target for 2030. A solution proposed by the State Forestry organisation to counter this problem has had a marginal effect.

- In one of the first decisions of Tusk’s climate ministry, logging was temporarily halted or at least reduced in 1.3 percent of state-managed forests. The locations were chosen for environmental and social significance. The coalition government has promised to increase protection of 20 percent of the public forests by the next election in 2027.

- The ruling coalition also wants to create new national parks, which Poland hasn’t done in over two decades, as well as expand existing ones. It notes national parks cover only 1.1 percent of Poland’s land area, compared to an EU average of 3.7 percent. It’s efforts to create the Lower Oder Valley National Park along the border with Germany, however, were blocked by the opposition-aligned president Karol Nawrocki, who argued that the park would “block the economic development of the region”.

Find an interviewee

Find an interviewee from Poland in the CLEW expert database. The list includes researchers, politicians, government agencies, NGOs and businesses with expertise in various areas of the transition to climate neutrality from across Europe.

Get in touch

As a Berlin-based energy and climate news service, we at CLEW have an almost 10-year track record of supporting high-quality journalism on Germany’s energy transition and Europe’s move to climate neutrality. For support on your next story, get in touch with our team of journalists.

Tipps and tricks

- CLEW’s Easy Guide to Germany’s transition with background information and links to key energy and climate data.