Germany’s Climate Action Plan 2050

Germany's grand coalition government of conservatives (CDU/CSU) and Social Democrats (SPD) has followed through on its coalition agreement to approve its Climate Action Plan 2050. It sets out measures aimed at making the country largely greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions-neutral by 2050, and following through on its commitments to the Paris Climate Agreement from 2015.

A press release and a short summary of the plan in English can be found here.

Earlier versions of the environment ministry’s plan had been trimmed down following objections within the federal government.

Recent ministry projections show that Germany is likely to miss its 2020 target of reducing GHG emissions by 40 percent compared to 1990. The Climate Action Plan 2050 says that emissions could be reduced by “about 37 percent” by 2020.

In light of the dispute over the environment ministry’s draft of the plan over the past months, some commentators fear that Germany’s days as a climate protection pioneer might be over.

In a press release on the climate plan, the federal government said Germany would reduce its greenhouse emissions by at least 55 percent compared to 1990 by 2030, and by at least 70 percent by 2040, which is largely in line with its previous GHG-reduction goals.

“With this, Germany remains a pioneer on how to put into practice the commitments of the Paris Climate Agreement,” the press release said.

Preamble

In light of the Paris Climate Agreement, the plan is presented as a work in progress and will be constantly updated. “It cannot and does not want to be a detailed masterplan, set for decades,” the text says, adding that there will be “no rigid provisions,” and the plan is neutral over which technologies should be deployed to meets its goals, and open to innovation.

“It offers guidance for upcoming investments, especially for the period until 2030. Concrete legislative measures will be taken by the German Bundestag,” according to the text.

In the preamble, which was added at the insistence of Angela Merkel's Chancellery, the government confirms its 2010 goal to cut GHG emissions by 80-95 percent. It also states its aim as making Germany "largely GHG emissions-neutral" by 2050, and meeting targets laid out in the Paris Climate Agreement.

The text points out that pledges made in Paris are not enough to limit global warming to 2°C, and that all countries need to “exceed their current commitments.”

The federal government is to put a special focus on maintaining the competitiveness of the German economy, according to the plan. “We want to advance the upcoming changes without structural ruptures. It’s about using the strength and creativity of the German market economy, as well as the forces of competition, to reach existing national, European and international climate protection targets.”

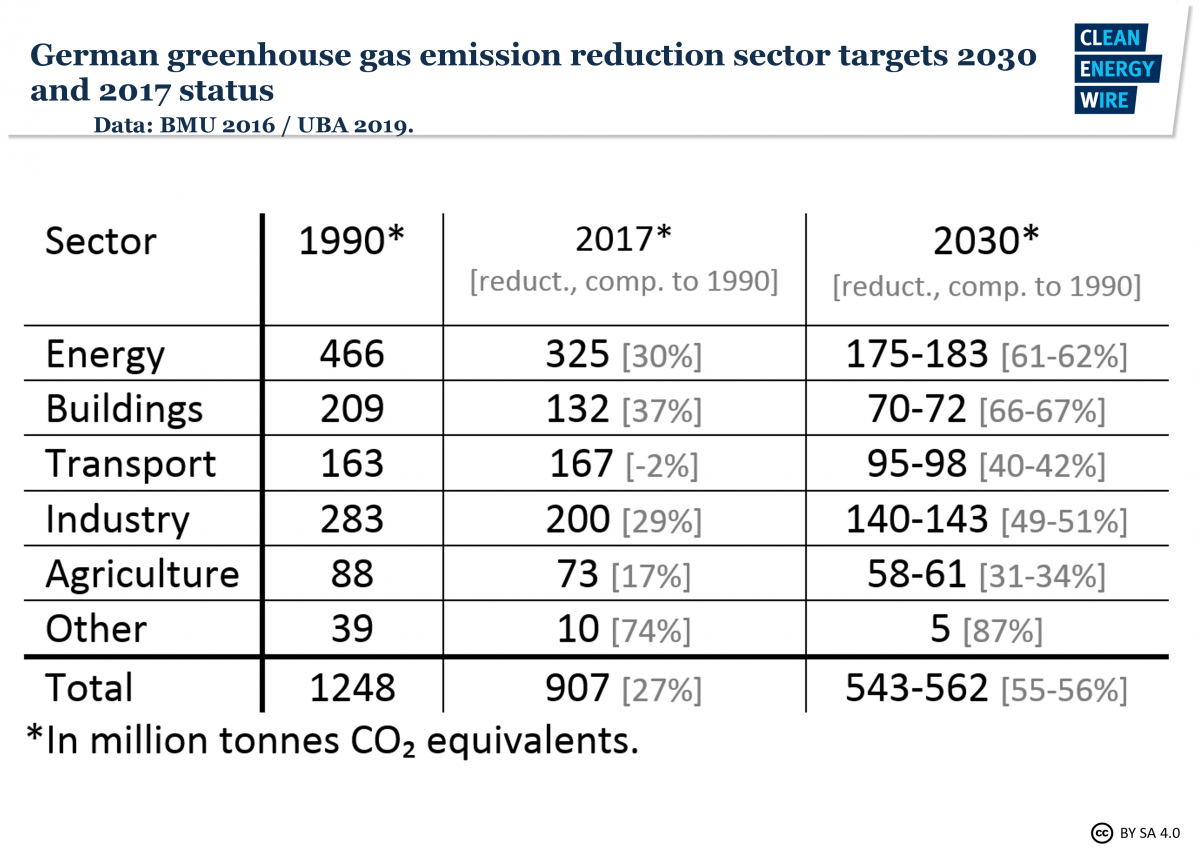

Emission targets for individual economic sectors

The Climate Action Plan 2050 introduces Germany’s first specific target corridors for each economic sector. Environment minister Barbara Hendricks said this would help avoid a blame game between the different sectors. “From today on, no one can talk her- or himself into believing that climate protection only affects others,” she said in a press release.

The plan says the sectoral targets could have “far-reaching consequences” for Germany’s economic and social development, and will be subject to extensive impact assessment to allow for revisions in 2018.

European Union Emissions Trading System (ETS)

The federal government continues to see an “effective” EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) as Central Europe’s main climate protection instrument for energy sector and parts of industry, according to the plan. It says strengthening price signals in emissions trading is a key concern, and the government will campaign to make the ETS more effective on a European level.

Energy sector

The energy sector will have to limit its GHG emissions to 175-183 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalents by 2030. This is a reduction of 61-62 percent compared to 1990.

By 2050, the energy supply must be “almost completely decarbonised” and renewables its main source. “In the long term, electricity generation must be based almost entirely on renewable energies. […] The share of wind and solar power in total electricity production will rise significantly.”

If “possible and economically sensible,” renewable energy will be used directly in all sectors, and electricity from these sources will be used efficiently for heating, transport and industry. There will be only limited use of biomass, mostly from waste.

Transitioning to a power supply based on renewables while ensuring supply security is “technically feasible,” according to the plan. During the transition, “less carbon-intensive natural gas power plants and the existing most modern coal power plants play an important role as interim technologies.”

Coal-fired power generation and structural change

“The climate targets can only be reached if coal-fired power generation is reduced step-by-step,” says the Climate Action Plan.

More and more investors have pulled capital from the global coal sector, according to the Climate Action Plan and “the federal German government in its development cooperation does not lend support to new coal power plants.”

However, the plan emphasises that jobs and the economic outlook in regions dependent on the coal industry – like east German Lusatia – must be taken into account.

“We must succeed in establishing concrete perspectives for the future of the affected regions, before concrete decisions on the step-by-step withdrawal from the lignite industry can be taken,” the plan says, adding that otherwise the Energiewende would lose credibility on a national and European level.

The plan includes a commission for “Growth, Structural Change and Regional Development,” but in contrast to an earlier proposal for a commission to set a date for the coal exit, coal is at no point mentioned explicitly in its remit. Instead, it is designed to “support the structural changes” brought on by the country’s transformation and will “develop a mix of instruments that will bring together economic development, structural change, social acceptability and climate protection.”

The commission will be linked to the federal economy ministry, and will involve other ministries, the federal states, municipalities and unions, as well as representatives of “affected” companies and regions. It will begin its work in 2018.

A regional fund is also to be established, to finance projects aimed at fostering new businesses in lignite mining regions. The German government is to ensure that EU competition law does not become an obstacle to such a fund. “It is in the interests of the whole of Europe that Germany achieves its disproportionately high share in Europe’s climate protection,” the plan said.

Building sector

The federal government aims to make Germany’s building stock largely climate-neutral by 2050. This means buildings will have very limited energy needs, which will be covered by renewables, according to the plan.

Because of the long lifespan of buildings, the foundations for a climate-neutral building stock in 2050 must be laid in 2030 already, says the plan. The building sector has to reduce its emissions to 70-72 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalents. This corresponds to a 66-67 percent reduction, compared to 1990.

The federal government will invest heavily in programmes to implement high energy standards for buildings, for example renovation and market incentive programmes to support renewable energies.

Heating, cooling and power supply will be switched to renewables, step-by-step. In 2020, the German government will stop support programmes for heating technologies that are solely based on fossil fuels and step up its support for systems based on renewables. The goal is to “make renewables-based systems much more attractive than fossil-fuel-based ones,” the plan states.

Transport

The plan does not set a deadline for all new cars to be emission-free, stopping short of earlier drafts and an initiative by Germany’s federal states.

It says stricter emission limits for new cars will be set at a European level, and that “the government will advocate ambitious development of the targets, so a reduction of transport GHG emissions to 95 to 98 million tonnes CO2 equivalents will be achieved by 2030.”

These cuts will be achieved by greater efficiency, and increased GHG-neutral energy, according to the plan. “This will have to take into account vehicles’ technical possibilities, as well as the economic effects on the affected players.”

To reduce car emissions significantly by 2030 will require “a significant contribution by the electrification of new cars and should have priority,” the document states.

At the same time, the climate plan emphasises the importance of biofuels: “In the target scenario, the energy supply of street and rail traffic, as well as parts of air and maritime traffic and inland shipping is switched to biofuels – if ecologically compatible – and otherwise largely to renewable electricity as well as other GHG-neutral fuels,” says the plan.

The government stresses the need for additional measures to support public transport, rail transport, as well as cycling. “The government will rapidly develop concepts to ensure the achievement of the 2030 milestone, and eventually the final target of almost greenhouse gas-neutral transport by 2050.”

The plan says the next necessary step towards 2030 transport target is to determine the framework needed to ensure that new propulsion technologies and energy forms will be used on a large scale. “This involves the question of when, at the latest, they should be introduced into the market, and what penetration rate they should achieve by what date.”

Industry

Emissions from the industrial sector will have to be cut in half by 2030, compared to 1990. A large share of this has already been achieved. The sector must still reduce its emissions to 140-143 million tonnes CO₂ equivalents, a cut of about 20 percent on today’s levels.

The Climate Action Plan emphasises the importance of ensuring the international competitiveness of German industry even with an ambitious climate policy.

“With our modernising strategy for the economy, the correct political framework, and active regional and structural policy that supports structural change, we want to create dependable framework conditions for the German economy, to adjust to this transformational process early, and use the possibilities connected to it,” the plan says.

Despite the costs and challenges for industry, climate protection could at the same time become an “innovation motor” for a modern high-tech Germany, according to the plan.

Some emissions from industry cannot be avoided, such as from steel production or chemical processes, the document states. The Climate Action Plan aims to reduce these emissions as far as possible, either by developing new technologies and processes to replace the old ones, or through Carbon Capture and Utilisation, as well as Carbon Capture and Storage.

Agriculture

As a reduction to zero emissions from agriculture is not possible due to biological processes in plant cultivation and livestock farming, the focus will be on reducing emissions as much as possible and more sustainable agriculture that uses resources efficiently, according to the climate plan.

The sector will have to reduce emissions by about a third by 2030, compared to 1990 levels.

About a third of emissions from the sector are nitrous oxide, resulting from the use of nitrogen in fertilisers. The federal government wants to reduce surplus nitrogen and will support research and development projects in this area.

Another third of emissions from the sector come from ruminant animals. The federal government will work out a comprehensive strategy to reduce emissions in livestock farming by 2021.

By 2030, 20 percent of all agricultural land “should be used for organic farming”, the plan says. In 2014, organic agriculture accounted for 6.3 percent.

The German government aims to use the EU Common Agriculture Policy’s financial instruments to reduce GHG emissions from agriculture, following reform of the policy planned for the coming years.

Land use and forestry

The land use and forestry sector offers the opportunities for carbon sequestration. The federal government is to make improving the performance of forests as carbon sinks a top priority. Permanent grasslands and marshes are to be preserved and sustainable forest management promoted.

The expansion of settlements and transport is to be reduced to 30 hectares per day by 2020, and to zero by 2050.

Climate-friendly development of the taxation regime

The German government will consider how to revise the tax system step-by-step by 2050, reasoning that “environmental taxes and levies can create incentives for ecological economic activity,” the plan says. “Environmentally related taxes and levies can cost-efficiently trigger climate-friendly economic behaviour.”

Climate friendly investment

The government plans to reduce subsidies that are environmentally harmful.

Efficient global financial markets

The federal government will support efforts to reconcile global finance flows with climate targets, for example through its involvement in the G20’s Financial Stability Board.

Implementation and revision of the Climate Action Plan

The Climate Action Plan 2050 will be reviewed every five years, in accordance with the revision of Paris Agreement commitments. Goals, paths and measures will be checked and – if necessary – changed in accordance with altered technological, political or social conditions. The first update of the plan is projected for late 2019 or early 2020, when signatories to the Agreement must submit revised goals.

As early as 2018 the government plans to bolster the climate plan with a programme of measures to quantify emission reduction effects and align them with an ecologic, social and economic impact assessment. These measures will be developed in consultation with the federal government. Additionally, an annual monitoring report should allow the government to readjust its procedures in the short term.