Greece must make up for lost time in climate adaptation

***Please note: This factsheet is part of a stocktake of climate adaptation efforts in Europe. Also read the main article Extreme weather forces unprepared Europe to focus on climate adaptation, the Q&A - Why Europe needs to adapt to the impacts of climate change, as well as the factsheet Europe steps up climate change adaptation in wake of floods and heatwaves.***

The entire Mediterranean is often referred to as a climate change hotspot, because the region is warming much faster than the global average, and is set to be affected by ever fiercer heatwaves, droughts and fires. Greece, with its economy dominated by tourism and agriculture, is one of the countries set to experience immense challenges in the decades to come.

In recent years, a string of devastating catastrophes was a harbinger of what is to come in a warming world. Floods caused immense destruction and paralysed entire regions. In 2017, 24 people were killed on the western outskirts of Athens, the country’s capital. The increase in wildfires has been particularly shocking. In the summer of 2018, 104 people were killed in the eastern suburbs of Athens in the world’s second most deadly wildfire of the 21st century. In 2021 alone, 1,300,000 acres were burnt - close to the combined area of all wildfires between 2013 and 2020. Images from the devastated island of Evia were seen around the world – most famously a photo of an elderly woman who cried out as fire approached her house, which won the World Press Photo award.

The long-term consequences of climate change are becoming increasingly apparent elsewhere, too. Greece has the longest coastline of any country in the Mediterranean, measuring almost 14,000 kilometres in total, and increasing sections are exhibiting alarming signs of worsening erosion. The agricultural sector, which is dominated by small-scale family farms and employs more than 500,000 people, is also facing turmoil because of changing rainfall patterns, an increase in heatwaves and droughts, and even cyclones.

](/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/adaptation-greece-unep.jpg?itok=7bFOn8fy)

Researchers and even certain authorities sounded the alarm bell over the serious impacts of climate change in Greece more than a decade ago. But the country has been consistently lagging in adaptation policies, meaning it must now make up for lost time, which makes the challenges even more urgent and difficult.

As early as 2011, a committee put together by the country’s Central Bank published a study on the future impacts of climate change, and called on the state to implement mitigation and adaptation strategies. The study estimated that the impacts of climate change could take 577-701 billion euros out of Greece’s GDP by the year 2100 – more than three times its current annual economic output. In February 2023, the Bank of Greece published an updated report in cooperation with the Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research, which confirmed the earlier estimate.

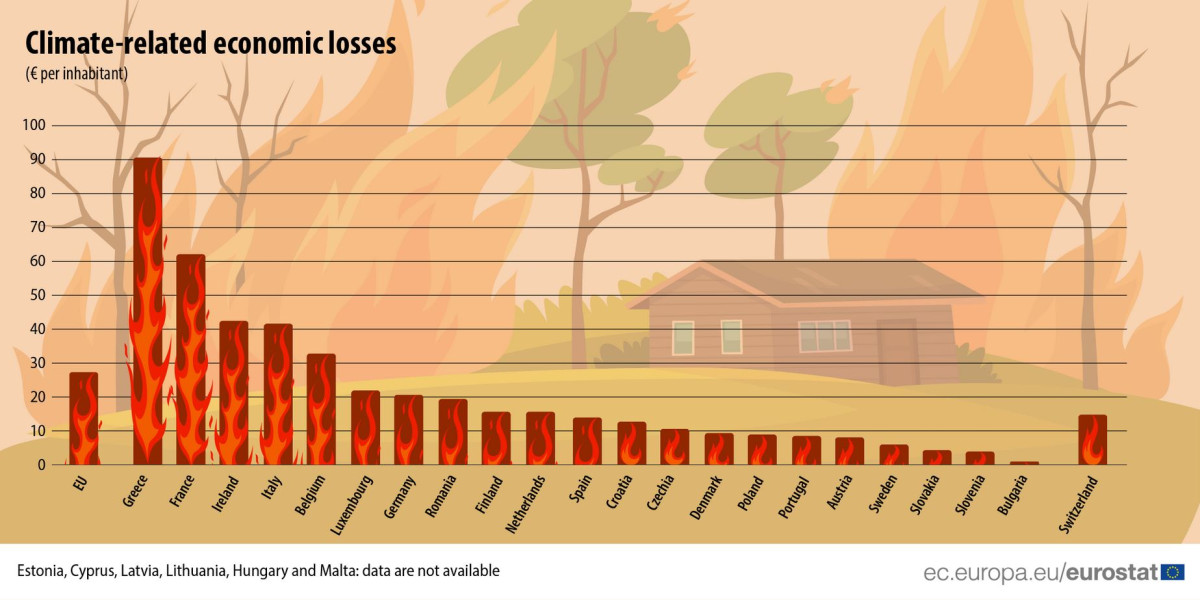

Greece already suffers by far the largest climate-related economic losses of any EU country. In 2020, the loss per inhabitant amounted to 91 euros, three times the EU average, and significantly more than in France, the second most impacted country, with 62 euros per inhabitant, according to Eurostat.

A series of decisions made by successive governments in recent years have shown that the country is at least acknowledging the urgency of the matter. Greece created a new Ministry of Climate Crisis and Civil Protection in 2021 in response to the disastrous wildfires, with the sole mandate of handling everything related to crisis management.

Putting together an adaptation framework has been challenging for Greece. In 2018, the country failed on multiple fronts in the European Commission’s Adaptation Preparedness Scorecard, which assessed EU member states’ adaptation strategies – or lack thereof. Among other problems, Greece had failed to integrate climate change impacts in its urban planning or crisis management plans; to institute cooperation mechanisms between authorities; and to monitor adaptation policies around the country. Despite these shortcomings, the Commission’s evaluation signalled significant progress, given that a national climate adaptation strategy (known as ESPKA) was only adopted in 2016. Since the country’s climate and economic conditions vary wildly from region to region, the strategy required Greece’s 13 regional governments (prefectures) to come up with adaptation strategies taking into account local specificities, which are currently awaiting completion and approval from the government to begin implementation.

Greece has been moving at a steady but slow pace on the issue of climate adaptation since establishing ESPKA in 2016. There are no actual adaptation projects underway, only the ongoing attempt to set up a framework that will eventually lead to designing and implementing adaptation policies.

In a November 2022 report, WWF Greece criticised that ESPKA is non-binding and “limited to conclusions, directions and advice,” and that the legal framework on adaptation is generally “deficient.” As for the regional plans, the “goals and measures or actions remain generic and the tools for their implementation are not available,” the WWF said.

One of the main problems so far is that adaptation plans have to be drafted and implemented on a regional level – but many local authorities are untrained, underfunded and understaffed. This is partly a result of Greece’s debt crisis of the 2010s, which left the country without the administrative and financial resources to implement a proper adaptation strategy, including a monitoring mechanism for the progression of adaptation projects. To overcome this problem, the Greek government applied to the EU’s funding instrument for the environment and climate action (LIFE) to ask for the financing needed to coordinate the adaptation strategy, help regional authorities draft their plans, address the knowledge deficit on the impacts of climate change, and make climate data publicly available.

The “LIFE-IP AdaptInGR - Boosting the implementation of adaptation policy across Greece” initiative is scheduled to run until the end of phase one of the Climate Adaptation Strategy in 2026. AdaptInGR aims to educate and assist local authorities in putting together regional adaptation plans, collect data on the impacts of climate change, and raise awareness among the public. Adaptation projects are expected to be completed in five cities by 2026: in Larisa, Katerini, Kamatero, Rhodes, and Ilida.

To name one example: Larisa, which according to the latest report by the Bank of Greece is one of the regions that are suffering the most intense climate pressures. The city has integrated a pilot programme for schoolyards into AdaptInGR. One schoolyard will be paved over with less heat-absorbing materials and equipped with covered spaces to protect students both from heavy rain and heatwaves, while another will reappropriate and increase its green spaces with the use of smart benches powered by solar energy and systems that will use a nearby stream to water the plants. According to the city, these projects will address rising temperatures, reduce the use of resources and also use real-time monitoring of local meteorological indices to educate students.

The 14-million-euro budget of the AdaptInGR initiative, which currently spearheads the National Strategy of Adaptation to Climate Change, is funded by the EU’s LIFE programme and Greece’s Green Fund. LIFE is also funding smaller, local adaptation projects, which are all the country has to show for now.