Climate change adaptation plans fall short in hard-hit Italy

***Please note: This factsheet is part of a stocktake of climate adaptation efforts in Europe. Also read the main article Extreme weather forces unprepared Europe to focus on climate adaptation, the Q&A - Why Europe needs to adapt to the impacts of climate change, as well as the factsheet Europe steps up climate change adaptation in wake of floods and heatwaves.***

A whole series of recent extreme weather events has brought wide attention to the effects of climate change in Italy. On 11 August 2021, a weather station near Syracuse on the southern island of Sicily recorded 48.8°C — likely the highest temperature ever measured in Europe. Only weeks before, the Marmolada glacier in the Dolomites had collapsed during one of the hottest summers ever recorded in the country, and then prime minister Mario Draghi said the incident was "without doubt" linked to climate change.

Spectacular climate change impacts didn’t remain limited to the summer months. In September, the Marche region in central Italy experienced heavy floods on the heels of one of the worst droughts in 150 years.

These are just some of the recent extreme weather events which underlined scientific warnings that Italy, and the Mediterranean in general, are already in the eye of the climate crisis storm. Average temperatures over the last 10 years in Italy were 2.1°C higher than in pre-industrial times, compared to a 1.1°C global average.

has a database of extreme weather events in Italy [CitaClima](https://cittaclima.it/mappa/) has an online database of extreme weather events](/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/adaptation-italy-database.jpg?itok=QewQXg5L)

It is now widely recognized that climate change will have a profound impact on Italy’s society and economy. In a report on ‘The effects of climate change on the Italian economy,’ the country’s central bank predicted particularly dramatic effects on food production. Italy is currently one of the EU’s largest agricultural producers and food processors, and last year’s severe drought caused crop yields to fall by up to 45 percent, while rice and wheat yields dropped 30 percent. “As a result of the drought, almost 8,000 fewer hectares of rice will be cultivated in Italy this year (2023), for a total of just 211,000 hectares, the lowest for thirty years,” according to Coldiretti, one of the major associations representing and assisting Italian farmers. Climate modelling suggests that by 2030, the country could experience a significant further loss of corn and wheat yields.

Research by the Euro-Mediterranean Centre for Climate Change (CMCC) also singles out the agricultural sector as being “particularly exposed to reductions in yields due to drought and water scarcity.” It forecasts a decrease of between 87 and 162 billion euros in the value of agricultural land by 2100 and says that Italy must prepare for heavy losses in the harvests of spring and summer crops, especially if they are not irrigated. There is also a potential shift in arable land towards the north of Italy for species such as olive trees and grapevines.

Winter tourism in the Alps is set to be heavily affected, too. Estimates indicate that a temperature increase of 1°C would be enough to raise the snow reliability line in the Alps to the point where all the installations in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region and about 30 per cent of those in Veneto, Lombardy and Trentino would no longer be viable. “Our results suggest that the impacts of climate change on winter tourism could be material and particularly severe for lower altitude ski resorts”, says the central bank’s report ‘Climate change and winter tourism: evidence from Italy.’

After almost four years of delay, the Italian environment ministry published the country's first National Plan for Adaptation to Climate Change in December 2022. The plan aims to provide a framework for minimising the risks of climate change, improving the adaptive capacity of nature, society and the economy, and on taking advantage of the opportunities that may arise from a warming world. It is the result of collaboration between research institutes, foundations and universities, coordinated by the Euro-Mediterranean Centre for Climate Change. After a public consultation, a final text is set be adopted by the end of March 2023, and be accompanied by the creation of a national observatory to ensure the immediate implementation of the plan.

The plan is “absolutely necessary in Italy” to make “our cities, countryside, mountains, inland and coastal areas more resilient to climate change,” in the words of environment and energy security minister Gilberto Pichetto.

A big chunk of the budget for the adaptation measures will come from the 71.7 billion euro National Recovery and Resilience Plan, which is meant to help the economy overcome the consequences of the pandemic. Fifteen per cent of this sum, around 11 billion euros, will be earmarked for climate change adaptation measures.

Other funding for adaptation measures could come from EU initiatives such as the LIFE programme for the environment and climate action, the European Regional Development Fund, or the Common Agricultural Policy. At a national level, measures aimed at protecting cultural heritage from the risks of climate change could also benefit from a separate programme which is currently under development. Similarly, research institutions or companies that start developing private technology solutions for adaptation could receive funding under the National Research Plan.

Still, there is widespread doubt that funding will be sufficient. A recent analysis by the think tank Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (Asvis) suggests at least 37 per cent of the national recovery plan should be set aside for climate action, more than double the current amount. “There is a lack of measures to strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related risks and natural disasters,” says the group.

A Climate Protection Act, already adopted in many other countries like Spain, Germany, and France, could also facilitate adaptation, according to a position paper by the Italy for Climate think tank. This legislation could help regions and municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants to adopt plans for climate adaptation measures and support local governments through a dedicated fund fuelled by revenues from the EU’s ETS (Emissions Trading System), the paper argues.

Many research projects are underway in Italy that could lead the way for future adaption measures. Most of these are carried out by research institutes, universities and coordinated by local governments or regions, and most of them are financed with European funds such as LIFE and the research and innovation funding programme Horizon, rather than coordinated at national level. However, many of the biggest cities and municipalities, such as the northern cities of Milan and Bologna, have also adopted adaptation plans, underlining that they are often coordinated at regional level, rather than national one.

In the agricultural sector, a project named Dromamed is focused on finding maize varieties that are more tolerant to drought and head using germplasm collections in various Mediterranean countries.

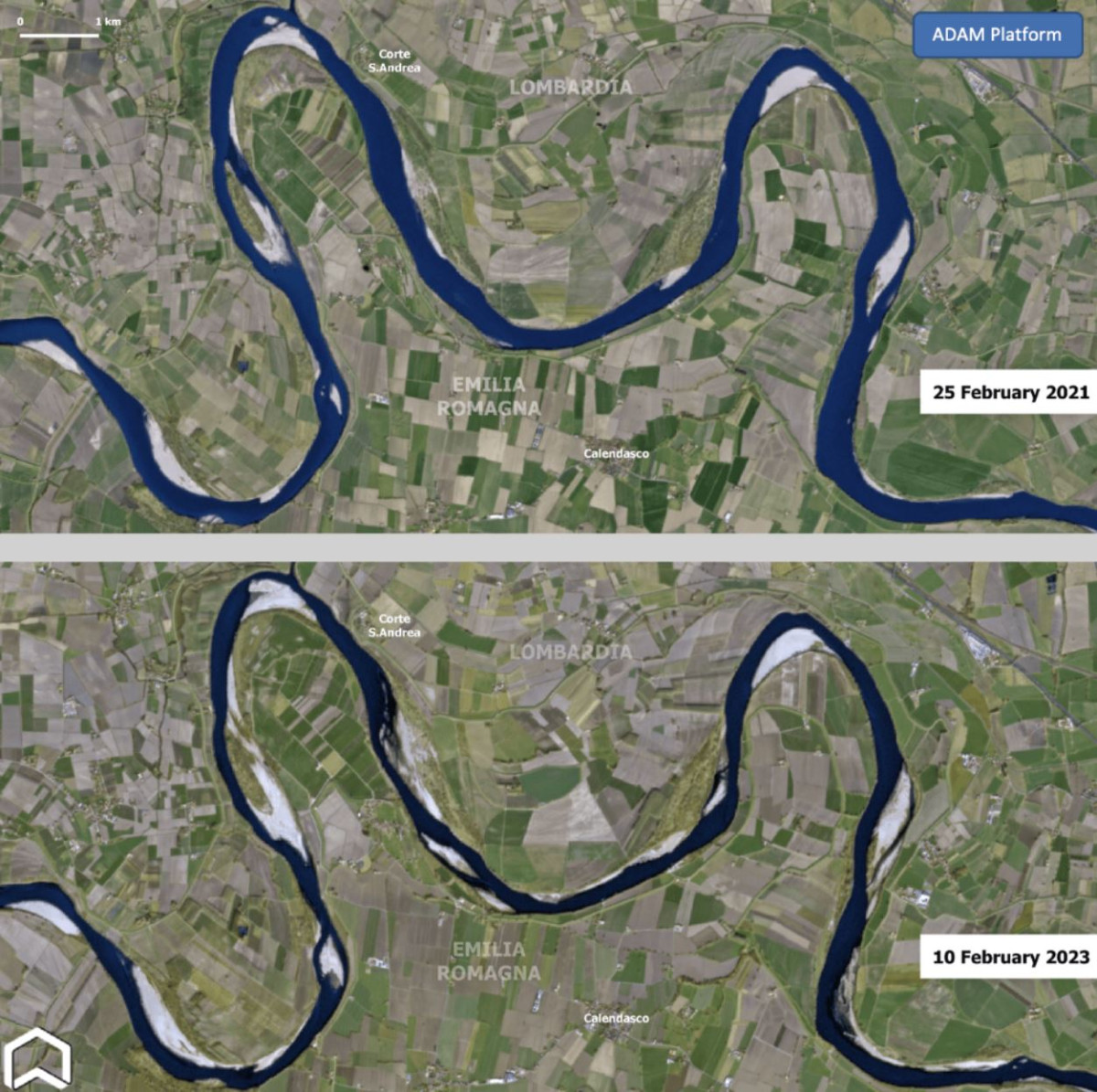

To deal with water scarcity in Po valley, Bosco Limite, a Natural Based Solution (NBS) project was launched in 2013 to convert 2.5 hectares of land that were used for corn over the previous 20 years into a forest. Today, the forest hosts 2,300 trees, whose species have been selected to recreate the typical environment of the venetian forest, and more than 20 different animal species. The project is the largest Forested Infiltration Area (FIA) in the region, a method to recharge groundwater aquifers by channelling surface waters into areas that have been planted with trees and shrubs.

To reduce coastal erosion and sea level rise, numerous projects are ongoing in many different coastal areas in the country. Some of these serve to restore seagrass meadows such as Posidonia oceanica to entrap the sediment, stabilize the seafloor and thus prevent coastal erosion during storms.