Q&A: German capital Berlin votes whether to make city climate neutral by 2030

](/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/berlin-2030-klimaneutral-poster-english.jpg?itok=CRdhQ7Kp)

A citizen's initiative had gathered enough signatures for the German capital to hold a vote on whether it should rapidly bring forward its plans to reduce its climate impact. However, not enough voters in Berlin supported a push to make the German capital carbon neutral by 2030, the preliminary outcome of a referendum held on Sunday showed.

The city of Berlin, like Germany as a whole, aims to become climate neutral by 2045. Its climate law forces it to cut carbon dioxide emissions 70 percent by 2030, 90 percent by 2040 and more than 95 percent by 2045, compared to 1990 levels. In 2020, emissions reductions were at 50 percent.

Climate scientists and activists have called out these targets for being too weak – they point to the dwindling amount of CO2 that can be released without heating the planet 1.5 degrees Celsius. If Germany were to emit no more than its fair share of it, the country would need to be climate neutral more than a decade earlier than it plans, according to the German Advisory Council on the Environment.

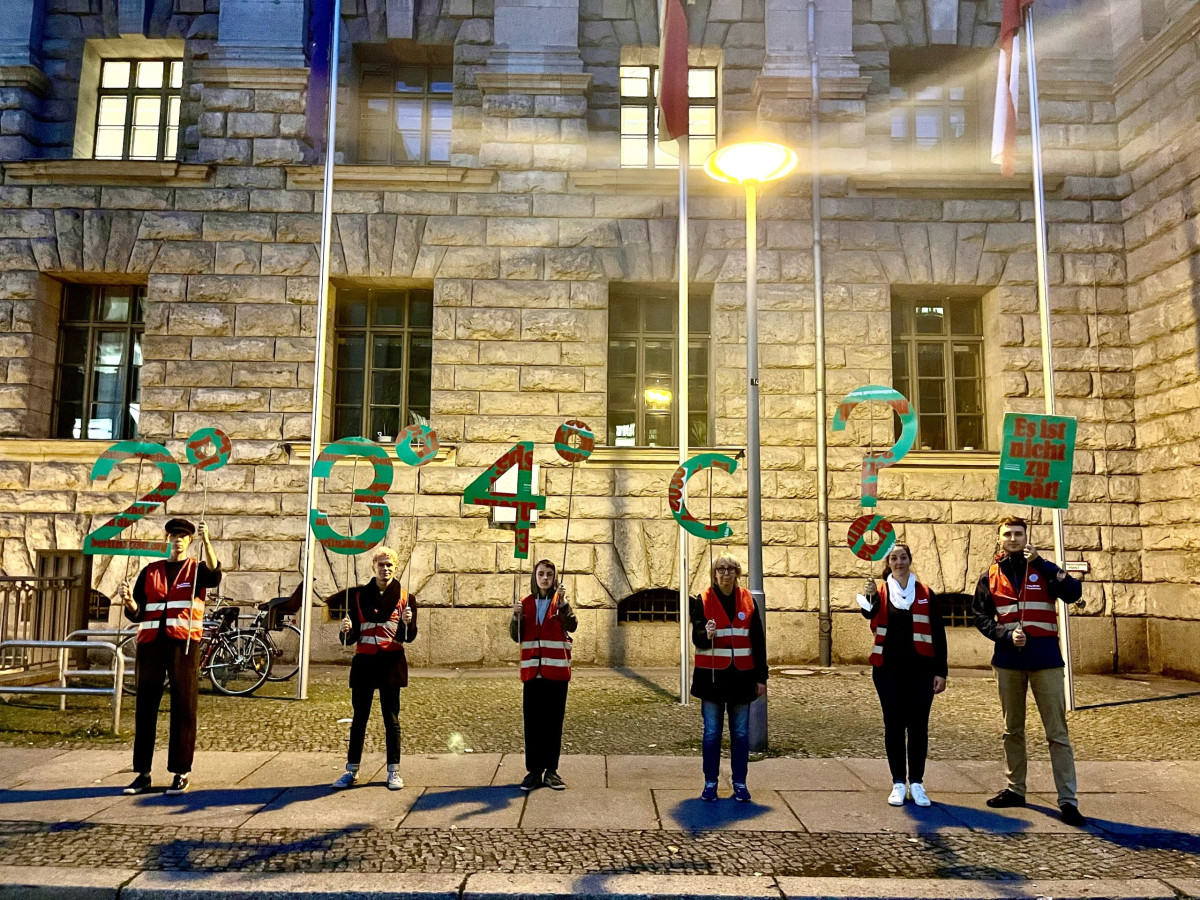

The proposal being put to the vote on 26 March applied the same logic to the city of Berlin to call for a 2030 climate neutrality target. A campaign group called Klimaneustart — with the support of local environmental groups, the environmental search engine Ecosia, and the German branch of student protest group Fridays for Future — wants to bring the date for carbon neutrality forward by 15 years, and also include other greenhouse gasses in the target. Emissions would have to fall at least 95 percent by 2030 and carbon offsets would have to be avoided unless there were no alternatives.

The update would also make the language in the law stronger, replacing words like "target" with "duty" and "achieve" with "fulfill." An intermediary target of a 70 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions would jump forward from 2030 to 2025.

"A lot of people see climate politics as a marathon," said Julia Epp, a scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and chair of the Berlin branch of Friends of the Earth Germany, which supports the campaign. "But it's more that we need to sprint because we started too slow."

If enough people vote yes, the Berlin senate will have to accept the proposed law amendment — and come up with a plan to cut its greenhouse gas emissions to net zero in 7 years. But the city parliament has the power to make further amendments to the law.

Only German citizens over the age of 18 who are registered in Berlin are eligible to vote in the referendum. Public opinion is slightly in favour of higher climate ambition. A poll from research company Civey conducted in January and February found 46 percent of Berliners were in favour of moving the climate neutrality target forward to 2030, while 42 percent opposed it and 12 percent were undecided.

But the results of the referendum are only valid if at least 25 percent of those who can vote agree with the proposal — about 613,000 yes votes — leaving some supporters worried about turnout. "It's a big struggle to motivate people to actually go to the referendum," said Epp. "We have a lot of people who are interested in climate politics and who will definitely go, but one fourth of Berlin's population? That's a lot of people."

To increase turnout, Germany often schedules public votes to coincide with elections. This time, the Berlin government has scheduled the referendum on climate neutrality for a weekend that is not connected to other votes. That could reduce turnout, lowering the chance of passing the 25 percent threshold. But it could also work in favor of the supporters — by reducing the number of votes from people who are disengaged and increasing the share of yes votes.

When the city had its last big referendum in 2021, 56.4 percent of those who voted said yes to a plan to expropriate biggest real-estate companies. Turnout was high enough to reach the threshold, but the proposal was non-binding and plagued by legal hurdles. In 2013, a referendum over buying back the city's electricity grid and speeding up the switch to renewables was won with 83 percent of the votes, but it narrowly missed the turnout threshold.

Berlin is both Germany's capital city and one of its 16 federal states. The key decisions for its decarbonization happen at a national or European level, but it can pass local laws to bring emissions down sharply — with more flexibility than most other German cities.

The three main areas of action for a city like Berlin are mobility, heating and new construction, said Felix Creutzig, a professor of Sustainability Economics at the Technical University of Berlin and co-author of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) fifth assessment report. "Berlin can do quite a bit in these fields, but it would depend on national level action."

Proposals that could cut emissions fast enough by 2030 include banning vehicles that run on fossil fuels from the city centre, restricting how much can be built, and swapping gas boilers for heat pumps, said Creutzig — adding that some tools may prove unpopular or come with trade-offs.

As well as the high-level emissions targets, the ballot paper includes proposals like retrofitting buildings to make them more energy efficient by 2030, a subsidy from the Berlin state to reimburse rent increases that result from the law, and measures to generate more renewable energy in public and private buildings.

Most political parties have rejected the petition. The senate’s official statement, from the incumbent coalition of the left, center-left and green parties, argues that the goal is unrealistic. It adds that “Berlin cannot decouple itself from [Germany and the EU’s] goals to the extent that it can single-handedly become climate neutral 15 or 20 years earlier.” In particular, it stresses that Berlin's ability to go carbon neutral depends on importing clean electricity from other states — and that the city has little influence over federal plans.

The Greens, who initially rejected the proposals, came out in support of the referendum earlier this year despite internal disagreements, and said that a successful referendum would constitute a “milestone on the way to a green and liveable capital city.” Bettina Jarasch, the Green party Senator in charge of Berlin's environment policy, told Germany's newspaper taz that she would vote yes in the referendum, while not thinking Berlin could achieve the goal. The success of a referendum can still help by giving politicians "more instruments in the hand" to make binding climate protection roadmaps, she said.

The current government will likely be replaced by a coalition between the centre-left SPD and center-right CDU after a recent election where transport, housing and energy were particularly contentious campaign issues. The Green party did well in central districts, while conservative parties, who campaigned heavily on cars, won votes in the suburbs.

](/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/berlin-2030-klimaneutral-arguments-english.jpg?itok=85OU4wse)

A study from the Institute for Ecological Economy Research (IÖW), commissioned by the Berlin senate to explore scenarios of how it can comply with its climate obligations, found the city could reach carbon neutrality in the 2040s. "In contrast, reaching the goal much earlier is unlikely," the authors wrote, who added that the city could reduce emissions two-thirds by 2030 only “with great efforts that start immediately” – and under the condition of more ambition at the national level, including a coal exit by 2030.

Even many supporters of the referendum say it is an illusion to believe that Berlin can become climate neutral by 2030. "My thesis is that we won't make it by 2030. I think 2045 is realistic," said Fritz Reusswig from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, who said he will still vote in favour to avoid a standstill on climate action under a city government led by the Conservative CDU and the Social Democrats (SPD), which looks likely following a recent city election.

Still, a handful of studies have explored how Berlin can clean up different sectors of its economy sooner. One study by the research group Fraunhofer Institute, commissioned by Fridays for Future and local environmental groups pushing to quit coal, found Berlin could decarbonize its district heating by 2035, and perhaps even 2030 — though to do so it would need to tap into land from the state of Brandenburg, which surrounds the city. Another study by Energy Watch Group, a non-profit founded by former Green party lawmaker Hans-Josef Fell, found the Berlin-Brandenburg region could make all the renewable energy it needs by 2030.

"The goal of the referendum is not underpinned with policies — and the policymakers don't have an idea of how to reach climate neutrality with policies," said Creutzig. "There's really a mismatch between ambitions and understanding what needs to be done."

Industry, for instance, would be particularly hard to clean up. It is unclear what the proposals would mean for companies for whom fossil fuels are hard to replace, particularly like cement makers, or for the city's airport.

"Conning Berliners into believing that the capital can become climate-neutral by 2030 is dishonest," said Christian Amsinck, head of Berlin industry lobby group UVB. "Anyone who stirs up other expectations among voters risks a further loss of confidence in our democratic system."

Still, other business leaders say the decision could spur needed innovation. More than 100 Berlin companies, including the online bank N26, have signed an open letter in support of the referendum, according to a list obtained by the newspaper Tagesspiegel.

Many companies are "inactive" on climate protection because there aren't reporting requirements, or because they are too small, said Katrin Lechler, CEO of Berlin-based manufacturing firm Stanova. "If there were not only targets but also sanctions for companies that aren't climate neutral by 2030, then… [climate] would become their top priority."

Last year, the IPCC found a growing number of cities were setting climate neutrality targets, but warned their full potential could only be met by addressing emissions beyond their boundaries. It found three key ways to cut emissions: cutting energy use, electrifying processes and swapping to cleaner energy sources, and storing more carbon in the urban environment — with things like green roofs, rivers and parks. Cities can also have knock-on effects across the country, it found, by pushing companies in their supply chains to clean up.

More than 100 European cities – including capitals such as Paris, Warsaw, Stockholm, Helsinki and Rome – have joined an EU initiative to start on the path towards 2030 climate neutrality. Berlin's referendum would see it adopt the same target but not make it part of the project, which includes 3 small German cities in the west of the country. The Danish capital Copenhagen aimed even higher — looking to become the first climate neutral city by 2025 — but its ambitions hit a roadblock after a waste incinerator failed to get funding to capture the carbon it emits, according to media reports.

Cities shooting for such high climate targets can teach each other what works, said Thomas Osdoba, who leads the EU's NetZeroCities program, adding that he expected some but not all of the 112 cities in the project to get there. "A city by itself cannot realistically drive to that level of outcome. It's not a question of money, it's not a question of policy, it's not a question of buy-in — it's all of those things working together."

Ajit Niranjan is a freelance climate reporter in Berlin, working mainly for German public broadcaster DW News. He writes articles, makes videos, and is a regular guest in the TV studio.