Q&A – CCS makes comeback as Germany and the EU strive for climate neutrality

- What are CCS and CCU?

- What role does CCS play on the path to climate neutrality?

- What are the limits of CCS as a technology to prevent greenhouse gas emissions?

- What is the EU’s stance on CCS/CCU?

- Is CCS banned in Germany?

- Do policymakers and the public support CCS in Germany?

- Where will CO2 be stored?

- Is there a business case for CCS?

- How risky is the technology?

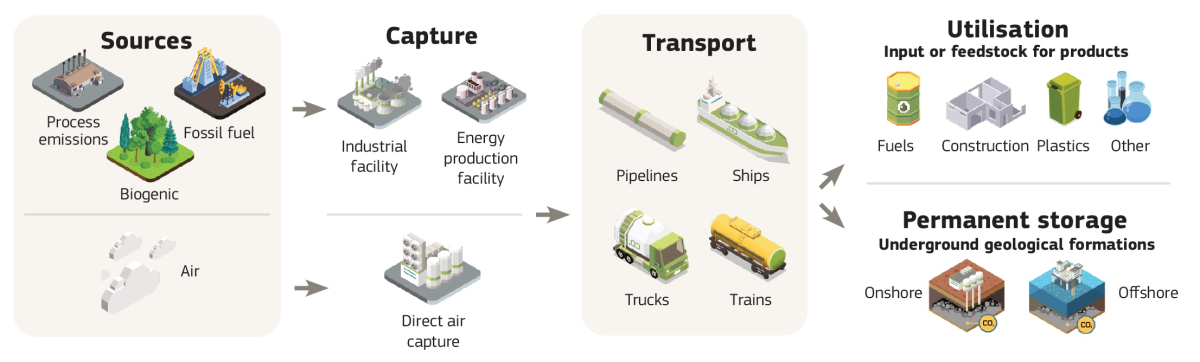

CCS refers to processes that separate CO2 from fossil sources in industry or energy-related processes, transport it to a storage location and isolate it from the atmosphere in the long term.

CO₂ can be stored in onshore and offshore geological formations, such as oil and gas fields, unminable coal beds and in deep special porous rock layers in which salt water occurs, so-called saline aquifers. The technology can also be used to create products, such as plastic, chemicals or fuels, in processes known as CCU – carbon capture and utilisation. In this case, emissions will eventually be released into the atmosphere.

There are several different ways of capturing carbon from fossil-fuelled power plants or industrial facilities (e.g. cement production), including post and pre-combustion methods. Most projects target large point sources of CO₂ and reutilise existing infrastructure, because using CCS on small and decentralised sources is considered too expensive and impractical.

CCS should not be confused with what is known as carbon dioxide removal (CDR), or “negative emissions,” although there is an overlap when it comes to transport and storage. CDR means the long-term removal and storage of CO2 from the atmosphere. This can include natural methods like afforestation and reforestation, as well as technological approaches, such as bioenergy carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS).

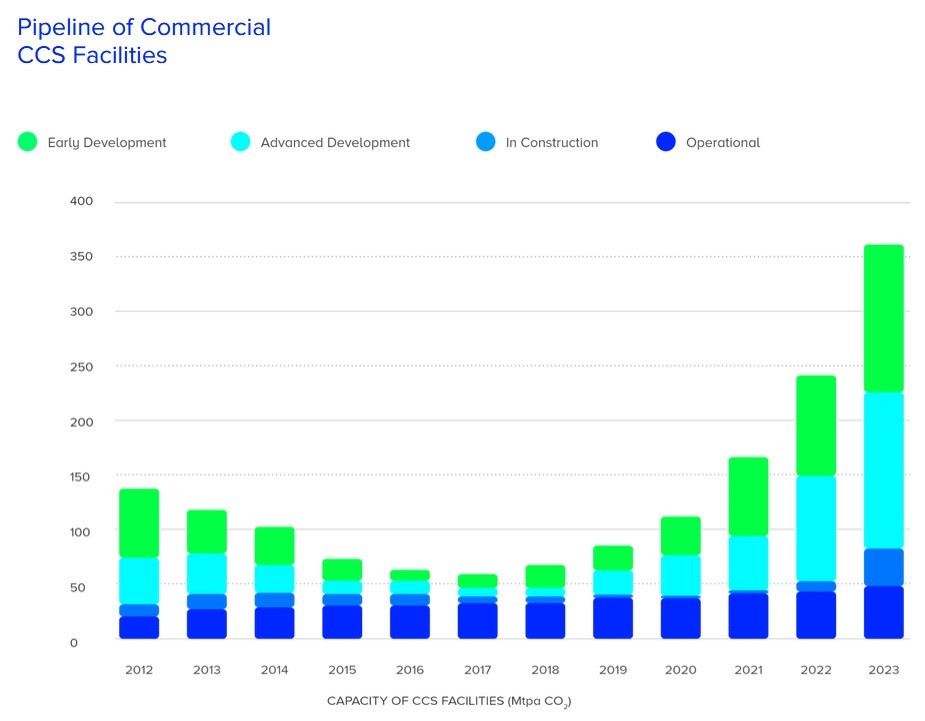

Overall, the deployment of CCS is still in its relative infancy. For the technology to really make a difference, the existing facilities need to be further developed, made much more efficient and set up for large-scale deployment up to gigatonnes per annum.

Most importantly until now, carbon has mainly been stored through a process known as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), which uses injected CO2 to extract oil that is otherwise not recoverable. In this process, parts of the CO₂ used stays underground. Critics say burning the additional oil emits more carbon than is being captured. The CCS industry was born out of the EOR in the U.S., the think tank Global CCS Institute said in its 2022 status report. Currently, only 25 percent of captured CO2 is injected for dedicated storage, the organisation said.

In mid-2023, the number of commercial, large-scale CCS projects in operation worldwide was 41 (with 392 in the pipeline and 26 under construction), of which 29 were EOR projects, the latest report said. However, 78 percent of CCS facilities under construction or in development plan to use dedicated geological storage, underlining a growing shift away from CO2 storage through enhanced oil recovery, the authors explained.

Critics have argued for years that CCS could be used to extend the lifetime of the fossil fuel industry, thus hurting the climate rather than helping protect it. With enhanced oil recovery at the centre of CCS projects so far, even more fossil fuel emissions are caused than without the technology.

Still, proponents argue that in the future, CCS technologies can help prevent considerable amounts of CO2 emissions from the industry or energy sectors from entering the atmosphere. Questioning the efficiency of the technology, experts argue that its deployment only makes sense in sectors where climate protection is particularly difficult. While emissions in the energy sector could be reduced to zero with renewable sources, some emissions in agriculture or from industrial processes, such as cement production, will be unavoidable in the long term, given the technologies known today.

Energy and climate researchers say CCS will be necessary to a certain extent to reach climate targets. All of the paths examined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for limiting global warming to a maximum of two degrees Celsius include a certain amount and certain forms of CCS. This applies even more to limiting it to an average of less than 1.5 degrees Celsius. According to research scenarios, the CCS requirement in Germany is likely to be around 34 to 73 million tonnes of CO2 annually by 2045, a third of Germany’s current industrial emissions.

EU's net-zero emissions plans shift focus to carbon management solutions

Though promising, CCS technologies have inherent limitations, as they are very energy-intensive and until now generally are not able to capture all emissions in a process. While current CCS technologies can capture 85 to 95 percent of a power plant's carbon emissions, their effectiveness is reduced by the additional energy required for capture, transport and storage, estimated at 10-40 percent compared to a plant without CCS, according to an IPCC report. Thus, the net reduction of emissions released into the atmosphere through CCS hinges on several key factors, i.e. the share of CO2 effectively captured, any leakage from transport or the increased CO2 production resulting from loss in overall efficiency of power plants or industrial processes due to the additional energy required.

The German Federal Environmental Agency describes CCS as a climate protection instrument that can neither replace greenhouse gas reductions nor the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels: CCS technology might be able “to conceal climate policy failures, but they cannot repair them,” the agency stated in a position paper in 2023.

At the COP28 UN climate change conference, CCS was a big point of discussion in connection with the possible agreement to phase out “unabated fossil fuels” (countries later decided to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems”). While some countries warned of weakening the necessary signal on fossil fuel phase-out, others wanted to limit it to unabated fossil fuel use, referring to “fossil fuels produced and used without interventions that substantially reduce the amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted throughout the life-cycle,” according to the IPCC. There is no agreement between countries on an exact definition of “abated,” and many argue that CCS should be seen as an abatement technology. The IPCC, meanwhile, defines mitigated emissions (“abatement”) as a reduction of 95 percent, which would exclude imperfect CCS processes.

Eventually, COP28 ended with an agreement on “accelerating zero and low-emission technologies, including, renewables, nuclear, abatement and removal technologies, such as carbon capture and utilisation and storage, particularly in hard-to-abate sectors and low-carbon hydrogen production.” However, there remains uncertainty about what “abated” means in practice. “A weak definition of ‘abated’ or no definition at all could allow poorly performing fossil CCS projects to be classed as abated,” the NGO Climate Analytics warns in an analysis.

The European Commission has made it clear that it sees CCS as key to reaching the bloc's climate targets. It presented its proposal for an European industrial carbon management strategy in February 2024, providing guidelines for capturing, transporting, trading, permanently storing and using carbon as an essential part of its move to climate neutrality by 2050. The Commission aims to set up "a European single market for industrial carbon management," to be ramped up over the coming years and decades to ensure that by mid-century, residual greenhouse gas emissions can be captured and stored, or balanced out through CO2 removals.

As part of its ambitious plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90 percent by 2040, the European Commission has spoken out in favour of CCS deployment at large scale, with a steadily rising carbon price in the ETS as a key incentive. The scenario assumes that of the 450 megatonnes (Mt) of CO2 captured per year by 2050, 250 Mt would be put in underground storage.

The rest would be used. The EU wants to "recycle" captured CO2 in the production of synthetic fuels (e-fuels) – for example for aviation – chemicals, or plastics to slowly replace the use of fossil fuel-based carbon, creating sustainable carbon cycles. The 2040 impact assessment says about 150 Mt would be used to produce e-fuels and 60 Mt to produce synthetic materials by mid-century. Most of these products would release the carbon back into the atmosphere when used, while some would store it more permanently.

Momentum for CCS continues to build in Europe. As of late 2023, there were 119 projects in various stages of development, construction or operation across Europe, according to the Global CCS Institute. Currently, four projects are in operation in the EU, Norway and Iceland. Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and Norway in particular, but also France and the UK, are driving the issue forward, with construction or advanced development projects that could be coordinated with each other, according to Germany's economy ministry.

North Sea sites continue to dominate as preferred locations for CO2 storage in the EU. Denmark is considering onshore storage, along with Poland, while other countries, such as Switzerland, Sweden, Finland or Belgium, rule out storage on land.

However, the EU’s active storage capacities are negligible, and so far, only tests have been carried out. The Danish "Greensand" project, for example, conducted a demonstration pilot in spring 2023 and injected smaller amounts of CO2 in a depleted well, with an expected storage of up to 1.5 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) from 2025-2026, rising to up to 8 Mtpa in 2030, a spokesperson told Clean Energy Wire.

It is, partly, but the government has aimed to adapt the legal framework to create areas of application in the country and to abolish existing hurdles to CCS/CCU.

Currently, there are different sets of rules for a) capturing emissions, b) storing and c) transporting CO2.

Capture: The construction and operation of a capturing plant is primarily subject to the authorisation procedure under the Federal Immission Control Act, according to a report of the NGO Bellona. Being subject to this authorisation requirement depends on whether the plant is particularly likely to cause harmful environmental impacts. There have been CCS pilot projects in Germany in recent years, such as the “Schwarze Pumpe” capture plant for demonstration in the German state of Brandenburg. Although there are currently no carbon capture plants in operation in Germany, it would already be possible to obtain the necessary approval under the Federal Immission Control Act.

Storage: For a while from 2012, Germany’s CO2 storage law in theory allowed the research, testing and demonstration of CO₂ storage to a limited extent. However, federal states can prohibit carbon storage in certain regions, and many German states have effectively introduced a complete ban. In any case, the law’s deadline for applications passed in 2016 without a single submission. Therefore, it is currently impossible to start a CO₂ storage project in Germany.

The German CO2 storage law implements the EU directive on the geological storage of carbon dioxide, which has been established to create standardised minimum requirements for CO₂ capture, transport and storage in the member states.

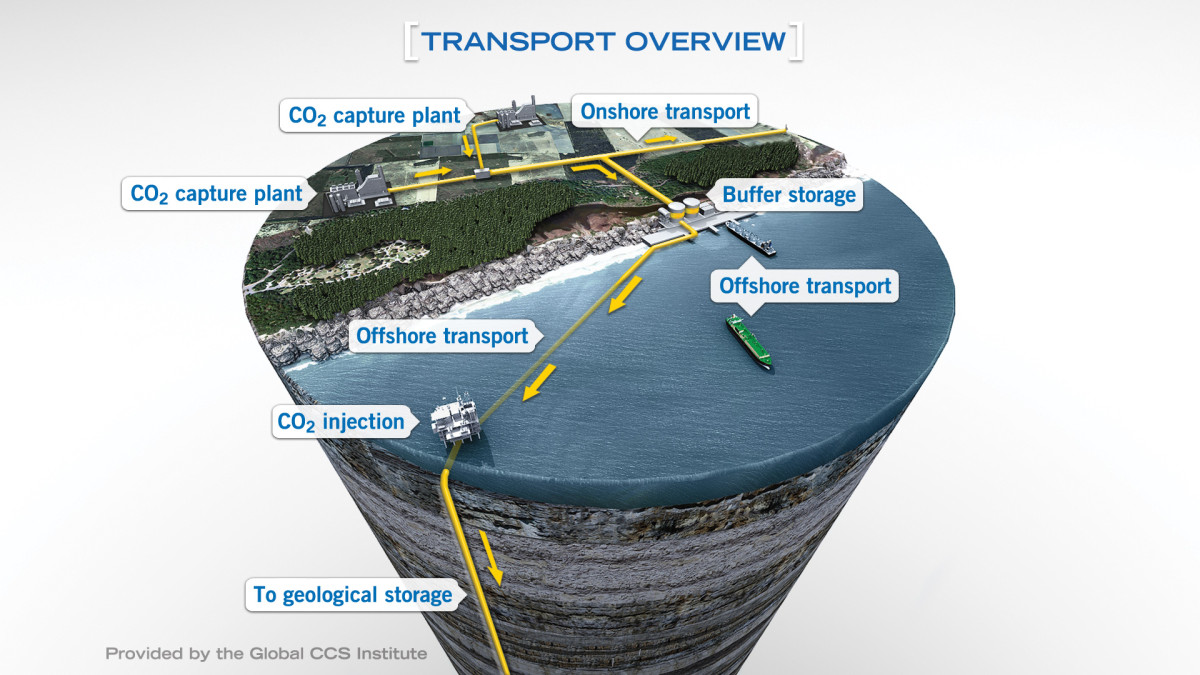

Transport: Transporting CO2 is also regulated by the CO2 storage law, with CO2 already being transported within Germany today via trains, lorries and ships, according to the German economy ministry (BMWK). Transport is also governed by the hazardous goods law. However, for transporting CO2 on a large scale a pipeline infrastructure is necessary, which currently does not exist in Germany due to legal uncertainty and “outdated regulations,” as the ministry emphasises.

Where things are headed:

Thus, the outgoing government wanted to change the legal framework, especially the CO2 storage law, arguing that the technology will be needed to reach climate neutrality. It presented key elements of a carbon management strategy, recognising the technology as mature and safe. According to those key elements agreed by the federal cabinet, the focus lies mainly on industries with hard-to-abate emissions, such as cement and lime industry, basic chemicals and waste incineration. Application for other industry processes would be permissible "as long as electrification or switch to hydrogen is not possible in a cost-efficient manner in the foreseeable future." CCS/CCU on gas-fired power plants would also allowed but receive no state support. Coal-fired power plants, however, would not receive access to CO2 pipelines and storages.

The government aimed to amend the CO2 storage law to enable the construction of storage facilities for commercial use on an industrial scale in the future. It intended to allow CO2 storage under the seabed, onshore, or abroad. Legislative revisions are also being made to abolish hurdles to new transport infrastructure projects and to establish CO2 pipeline networks.

However, due to the government break-up and disagreements in parliament, the proposed changes were not adopted in the last legislative period. The prospective coalition government of conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the SPD has said that it aims to adopt a legislative package to allow CCS “especially for hard to avoid industry emissions immediately at the start of new legislative period.” Coalition talks were ongoing by early April 2025, and details unclear.

According to the CCS lobby organisation Zero Emissions Platform (ZEP), there are currently five CCS/CCU projects in Germany that are on track to become operational before 2030, if supportive policy and financial frameworks are in place (as of March 2024). Two projects include CCS in industry, while another is researching and piloting a CO2 pipeline infrastructure.

In a Q&A document, the German economy ministry emphasises that the application of CCS/CCU must be in line with the greenhouse gas reduction targets of the climate action law and the achievement of climate neutrality by 2045. If the planned legislative amendments came into force quickly, a ramp-up by 2030 seems realistic, the ministry says.

At the end of February 2024, the German government presented plans to make CCS possible to help the country reach greenhouse gas neutrality by 2045 and as a solution for difficult-to-avoid residual emissions, and refined these in later decisions.

The country has a long history of public opposition to carbon storage, with the Green Party among its fiercest critics for a long time. People have worried about what is often portrayed as the uncontrollable risks of storage and oppose using it as a lifeline for coal-fired power plants.

Economy minister Robert Habeck’s own party and lawmakers from the governing coalition partners Social Democrats (SPD) have already come out against certain elements of Habeck's plans, promising difficult debates in parliament. "The Green parliamentary group rejects CCS for gas-fired power plants," said Lisa Badum, climate policy MP from the Green Party. At their national party conference at the end of November 2023, the Greens only supported a change of course on unavoidable emissions. Previously, the party had strictly rejected the technology.

Organisations such as Greenpeace, Environmental Action Germany (DUH) and Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) are still opposed to CO2 storage. The DUH, for example, criticised the government’s carbon management strategy as a “roll-back towards the fossil-fuel past,” calling on the federal cabinet and Bundestag (lower house of parliament) not to approve the proposal. “On the one hand, Habeck is allowing life-extending measures for fossil fuel, gas-fired power plants, while on the other hand he is turning the North Sea into a fossil fuel disposal park,” DUH head Sascha Müller-Kraenner said.

Opening up the strategy for gas, building larger infrastructures than necessary and shipping CO2 on a large scale is not the solution.

However, there is growing support for CCS and CCU among industry, trade union and several environmental NGOs, calling on the government to define a legal framework for dealing with CCU/CCS. Although WWF Germany was also part of this alliance, it criticised some of the key points presented by the government. "It came as a surprise that the government intends to allow CCS at fossil gas-fired power plants," Viviane Raddatz from WWF Germany told Clean Energy Wire, adding that this would be problematic both for its acceptance in Germany and as a political signal abroad. "Opening up the strategy for gas, building larger infrastructures than necessary and shipping CO2 on a large scale is not the solution," Raddatz said.

Industry and business stakeholders welcomed the key points of the carbon management strategy in February 2024, calling for it to be translated into a legal and financial framework rapidly.

In an online survey conducted by pollster Civey and commissioned by news magazine Der Spiegel in 2023, 55 percent of respondents said that they were not familiar with CCS, while around 39 percent said they knew about the technology. The respondents were also asked whether they would accept the storage of carbon dioxide in deep layers of rock if their region was suitable for such a project: While 50 percent of the respondents were in favour or somewhat in favour of it, 30 percent were against or somewhat against it.

Storage is possible in depleted gas or oil reservoirs, saline aquifers or in the seabed, in Germany for example under the North Sea as well as along the Upper Rhine and in the Alpine foothills. The Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) estimates that saline aquifers in Germany have a total CO2 storage capacity of between 6.3 and 12.8 billion tonnes. Additionally, depleted natural gas fields in the country can store around 2.75 billion tonnes of CO2, while depleted oil deposits can accommodate approximately 130 million tonnes of CO2.

First government proposals say the country would allow exploration of offshore storage sites in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EZZ) or the continental shelf, under specific conditions. The injection of carbon dioxide in marine protected areas and a surrounding buffer zone is excluded. Furthermore, Germany will ratify the amendment of the London Protocol to allow CO2 export for storage offshore in other countries. Federal states could opt-in to allow onshore storage on their land, but it is unclear whether any state would do so.

There have been several research initiatives in Germany, some financed by the government, which looked into the feasibility of carbon storage, examined capturing technologies or facilitated the scientific debate around CCS in general. Since the entry of the CCS law into force in 2012, no storages or pipelines have been applied for, approved or built. The Ketzin pilot site, 40 kilometres west of Berlin, was the first European onshore storage project and the only German one that got to a point where CO2 was actually injected into the ground.

Aside from projects that use carbon for enhanced oil recovery, CCS has not been proven economic at scale. Following estimations by the IPCC, CO2 capture currently costs more than 50 U.S. dollars per tonne for most technologies and regions, with some technologies much more expensive. Regarding storage, the German research consortium CDRmare speaks of a total of 70 to 150 euros per tonne of CO2 for injection in the North Sea.

Storing CO2 under the sea is a more expensive solution than storing it onshore, as the new infrastructure required in the sea – for example off the coast of Norway – needs to be significantly expanded and the pipeline network for transport to the coasts must also be established. However, betting on offshore storage is intended to increase social acceptance and prevent public protests, which led state governments around 2012 to put a stop to CCS on their territory.

Transport costs hinge on various factors, such as the transport method (pipelines or ships), whether CO2 is transported onshore or offshore, the distance and scale. Following the IPCC, these factors have the potential to double the cost per unit length, particularly amplifying the expenses for pipelines constructed in populated areas. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in the United States, the costs associated with onshore pipeline transportation span from 2 to 14 U.S. dollars per tonne of CO2, while the cost of onshore storage shows an even wider spread. However, more than half of onshore storage capacity is estimated to be available below 10 dollars/t CO2.

Monitoring will also have its price, for example the permanent search for leakages, observation of seismic activity during and after injection or a thorough geological site examination before a facility is built. The German Federal Environmental Agency points out that those costs have so far been "significantly underestimated,” calling for a common understanding of the costs attached to sufficient monitoring over centuries.

While allowances to emit one tonne of CO2 trade at around 60 euros in the EU's emissions trading system (as of March 2024), the price is expected to rise further in the future. At the same time, it can be assumed that CCS costs will fall with the further development and implementation of CCS technologies, thus strengthening the business case for the technology with a potential shift from a cost to a source of revenue.

One of the foremost economic hurdles facing CCS involves the substantial initial investments required for constructing carbon capture facilities, along with developing transport and storage infrastructure. Storage facilities close to emitters are more cost-effective, as these avoid the need for long-distance transport. Nevertheless, the storage locations must be regularly checked and maintained, thus the long-term follow-up costs must also be considered, possibly for centuries. While in the early development phase of CCS/CCU mainly full-chain business models emerged, part-chain business models are increasingly evolving, according to the IEA. Shifting risk allocation across the value chain, those business models are now rather characterised by separate companies specialising in different parts, i.e. focusing only on transport, that are connected to shared infrastructures.

However, the level of policy support from governments reached an historic high in 2023, the Global CCS Institute argues, making CCS projects more profitable in the future, as countries increasingly also provide state support. Especially the introduction of policies and regulations like the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the EU’s Fit for 55 package have prompted an exponential increase in announcements of investment in CCS, according to the institute. The German carbon management strategy is also to become the basis for the development of a CO2 infrastructure. The German economy ministry is already planning CCS/CCU funding totalling 1.3 billion euros.

According to the IPCC, CCS may have negative environmental effects, such as the risk of carbon leaks from storages or transport pipelines, or saline water being pushed up towards groundwater levels due to high underground pressure. However, the IPCC as well as the German BGR consider those risks to be minor, especially in suitable geological locations and with professional risk management.

In normal operation, the German Federal Environmental Agency points out that no health effects for humans are to be expected. The IPCC, too, says that the local risks associated with CO2 pipeline transport could be similar to or lower than those posed by already existing hydrocarbon pipelines.

The German CO2 storage law already contains legal requirements regarding the safety of CO2 storage facilities for demonstration. A potential CO2 storage plant may go into operation only if risks to people and the environment can be ruled out and the necessary precautions are taken to prevent adverse effects on the environment, in particular by preventing leaks. The government’s proposal to amend the CO2 storage law also emphasises the importance of examining possible environmental impacts and the safety of potential storage facilities in each individual case. Authorisation of storage plants is expected to be granted as part of a planning approval procedure, including an environmental impact assessment.

As CO2 is only intended to be stored offshore in Germany, climate and environmental protection organisations are criticising storage in the German part of the North Sea in particular - and the associated risks to human health and marine life. Due to decades-long extraction of oil and gas, there are drilling holes in the ground under the North Sea from which carbon could leak. However, there are only a few of these in the German North Sea, Klaus Wallmann from the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel told Deutschlandfunk, considering the technology to be “very safe.” The greatest risk of carbon leaking is during the injection process due to rising pressure, he said. However, in the long term, 99 percent of the stored gases could be kept in the ground, with the ecological damage to the seabed limited to small areas only, he said.

CCS can have negative environmental effects, which the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) assessed in a 2018 report. There is the risk of carbon leaks from storages or transport pipelines, or saline water being pushed up towards groundwater levels due to high underground pressure.

This is not so much an issue during regularly intended operation. Here, most of the potential effects “can be regulated in the framework of approval proceedings through conditions, avoidance and compensatory measures,” according to the UBA. Accidents, however, could lead to large amounts of CO₂ emitted into the surrounding area in a very short time.

CO₂ is a colourless and odourless gas. On land, the CO₂ will accumulate near the ground due to its greater density than air. At high concentration, this can become harmful to humans and animals. It would also lower the pH-value in groundwater and soil.

Injecting carbon into the ground can also induce seismic activity. There have been only a few instances where the seismic activity caused in large-scale storage projects or EOR was strong enough to be felt by humans. However, injecting carbon could potentially cause earthquakes that damage buildings or harm people.

Under the sea, carbon is largely diluted in the case of a leak. A strong increase of CO₂ concentration and acidification effects are to be expected primarily on a local scale, with potentially harmful or fatal effects on marine life.

Chemicals used in the process of capturing carbon can also become an issue for health and the environment and building up a CCS infrastructure will have consequences for the environment due to the construction of above-ground facilities such as injection systems, pipelines and access roads.

There are a myriad of environmental effects that could derive from implementing CCS on a large scale, as this could involve fundamental changes in the energy system, such as a shift from coal to gas in certain areas. While coal emits more CO₂ than gas when burned, methane is a more potent greenhouse gas, so the climate effects might be similar if methane leakages along the value chain are not kept in check.