Wealthy nations’ $100bn climate finance pledge delayed to 2023

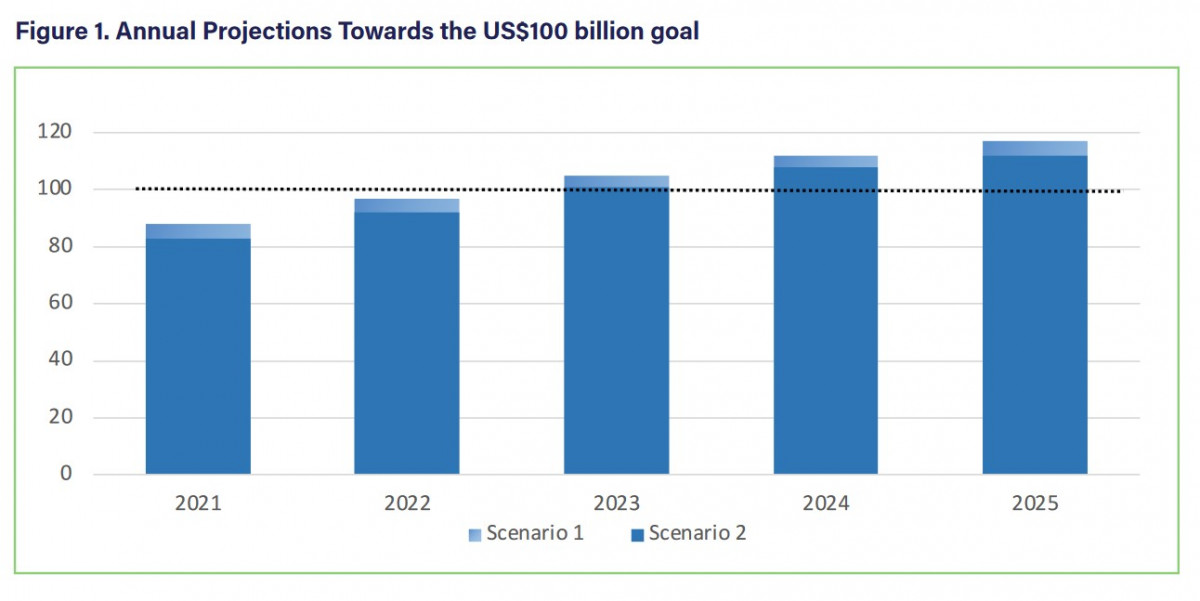

Wealthy nations have said they will fulfil their pledge to deliver 100 billion US dollars per year in climate finance to developing countries by 2023, three years later than originally promised. However, a climate finance delivery plan prepared by Canada and Germany for the UK presidency of the upcoming UN climate change conference COP26 states that countries could overshoot the target in the years thereafter.

“We will not be there in 2022, but in 2023 we will finally reach or even surpass this target,” said German state secretary in the environment ministry Jochen Flasbarth at a press conference. “Still, I urge developed countries and multilateral development banks to continue in their effort to even increase climate finance to the highest possible range.”

Climate finance will be key at the COP26 in Glasgow later this month. The delivery plan is meant to send a signal of trust to developing nations and thus ensure a successful conference.

“Our work continues but we have reached a significant milestone today,” said COP26 president Alok Sharma at the press conference. “One that I hope will start to restore trust and build momentum in this final stretch ahead of COP26.”

At the UN climate change conference COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, developed nations committed to mobilising 100 billion US dollars from public and private sources per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries. The money should help poorer countries to reduce their emissions and adapt to the effects of climate change. The goal was formalised at COP16 in Cancun, and at COP21 in Paris it was reiterated and extended to 2025.

However, recently published figures by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed that climate finance for developing countries in 2019 amounted to about 80 billion dollars only. It is clear that support for 2020 will remain well short of the target, but appropriately verified data for that year will only be available in early 2022, the OECD said. Recent estimates based on current plans and pledges made by Oxfam have shown that wealthy governments would continue to miss the 100 billion US dollar goal even in 2025 if nothing changed.

Together with Canadian environment and climate minister Jonathan Wilkinson, German state secretary for the environment Jochen Flasbarth was asked by COP26 president Alok Sharma to spearhead the preparation of the “climate finance delivery plan”.

“Jonathan [Wilkinson] and I really pushed developed countries during the last weeks very hard and not all of our conversations were polite,” said Flasbarth. “There is a disappointment which we share, but the result we have now is not bad enough, I would say, for allowing not to be constructive in Glasgow. Now we urge all parties to come to Glasgow in a spirit to solve the remaining issues.”

The new climate finance plan will only be one element in the greater area of international climate finance, said Pavel Zámyslický, the Czech Republic’s chief climate negotiator. “The plan prepared by Germany and Canada will open up debates on future goals. But I don't think it will finish the job,” Zámyslický, who leads the energy and climate protection department at the ministry of the environmentof the Czech Republic, told Clean Energy Wire.

He said climate finance will be the “most difficult” issue at COP26. “In the end, it may more or less paralyse COP26,” he warned. “Just as reducing emissions is important to us, it is likewise important for some poorer countries to get some new finance out of the negotiations to help them mitigate or adapt. These are extremely complicated negotiations,” Zámyslický said.

The delivery plan sets out an estimated trajectory of climate finance from 2021 through to 2025 - taking into account new climate finance pledges from individual developed countries and multilateral development banks. The three politicians said that in talks several governments had made additional pledges, but these would only be announced at COP26 and were not yet included in the plan. The plan to meet the target by 2023 does not rely on a significant improvement of private climate finance, said a press release.

NGOs were quick to criticise the plan. It “falls short of committing to meet 600 billion dollars over 6 years, or offering a serious scaled-up adaptation finance target for 2025,” said Iskander Erzini Vernoit, policy advisor on climate finance at think tank E3G.

Jan Kowalzig, international development organisation Oxfam’s senior climate change policy advisor, said: “Unfortunately, the plan does not contain enough information to really verify the claim made in it.”

“Instead, it relies on the self-reporting of donor countries which allows them to grossly over-estimate the value of the support they provide.” Kowalzig also criticised that the plan “conveniently fails to mention” the funds that poorer countries are owed for every year wealthy nations fall short. “This shortfall, which started to accumulate in 2020, will likely amount to several tens of billions of dollars.”

In any case, “100 billion US dollars is not enough,” Kowalzig told Clean Energy Wire. “It is a political figure pulled out in 2009 and it is outdated for two main reasons already. The goal was set in the context of the 2°C benchmark at the time. Now the benchmark is 1.5°C under the Paris Agreement,” he said. Countries thus need more support, and countries should debate what happens after 2025 at COP26 in Glasgow.

In recent weeks, the key players have announced their intention to raise their contributions to meet the 100 billion U.S. dollar goal. U.S. President Joe Biden told the United Nations General Assembly in September that he would work with Congress to double the funds by 2024 to 11.4 billion U.S. dollars per year. A week earlier, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that the bloc would add another four billion euros for climate finance by 2027.

Europe’s largest economy Germany has also said it would do more. At the G7 summit this summer, the German government announced that it would raise its federal budget contribution for international climate financing from the current four billion euros to six billion euros annually by 2025. According to Kowalzig, it is a step forward but Germany should increase its contribution even more.

“There is room for improvement. Germany should contribute its fair share to international climate finance,” he said. “Of course, in comparison with some other countries, Germany is a bit ahead. We recognise that but we think that the country´s contributions to these international challenges like the climate crisis should not be based on what other countries are doing or not doing but on what is fair and right to do.” Germany should increase its contribution from public funds to at least eight billion euros per year.

While several countries have raised their voluntary pledges, others have not. The Czech Republic, which is going to lead the European Union delegation at the next UN climate change conference that will likely take place in Egypt next year, has recalled its contribution to the Green Climate Fund during the pandemic and will now provide climate finance only on a bilateral basis.

“The current Czech government has decided not to contribute to the fund. This issue will remain open for the new government. Contribution is still open, so states can join at any time,” Pavel Zámyslický told Clean Energy Wire. After a national election earlier this month, a new government has yet to be installed in the country.