Green and sustainable finance in Germany

Energy transition pioneer Germany latecomer to climate action in financial sector

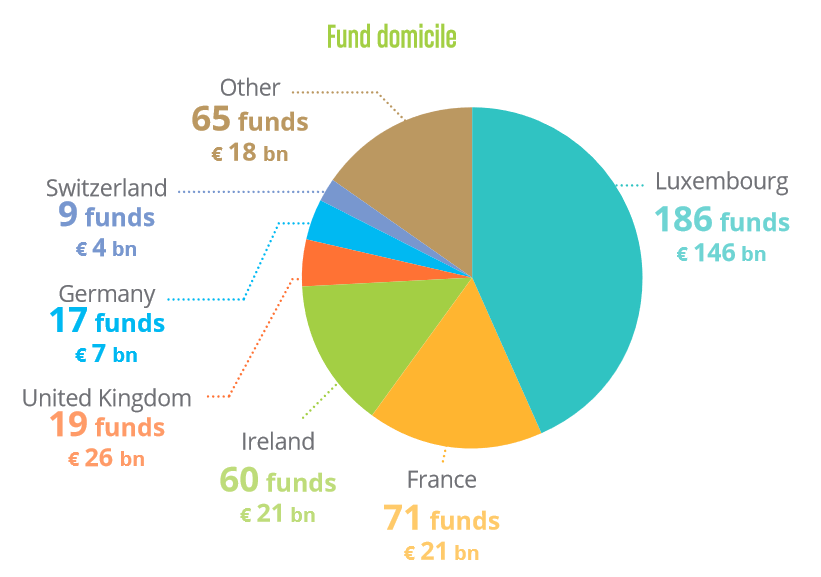

Despite its reputation for being a pioneer in renewable energy years of experience in implementing the energy transition, Germany has long been considered an international laggard in promoting and exploiting the potential of sustainable finance for its climate and energy policy. As the integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria became more widespread among financial institutions in recent years, Germany still trailed many European countries on most sustainable investment metrics analysed by industry network European Sustainable and Responsible Investment Forum (Eurosif). Green finance researcher Novethic in its 2021 European green funds report found that, as the biggest economy in Europe, Germany accounted for merely 7 billion euros out of a total of 243 billion euros in the region’s market for funds with a sustainability label.

But the interest in sustainable investments picked up considerably in Germany in the past years, both in terms of investors increasingly looking for corresponding financial products and the government attempting to better integrate the financial sector with climate and other environmental policies. Regulation at the EU level has played a key role in driving forward activities in Germany, but also a clear and sustained trend among investors to actively seek more transparency on the social and environmental impact of their investments. Between 2019 and 2020 alone, Germany sustainably managed investments in Germany grew by about 35 percent, according to the 2021 report of finance industry association Forum Nachhaltige Geldanlagen (FNG).

With over 80 percent, the bulk came from institutional investors, but volumes held by smaller retail investors grew much faster and expanded nearly 120 percent in year as a result of increased awareness and more available sustainable finance products, FNG said. German Fund Association BVI said that extraordinary growth in the market continued apace in 2021, as rising inflation rates generally let people invest their money. However, the share of sustainably managed funds and mandates still stood at under 6.5 percent in that year. The FNG report focusses on funds and asset management and does not cover lending. However, it clearly shows that the vast majority of investments were made without regard to the impact they have on emission levels or other critical climate and energy policy aspects.

"Traffic light coalition"

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, many governments began reviewing their national financial sectors’ structure and stability. With the financial dimension of climate policy becoming more measurable, many have also begun to more systematically integrate finance in climate policy. France, for example, has been compelling investors by law to disclose the carbon footprint of new projects since 2015, Norway has been integrating sustainability criteria in its influential government pension fund since 2010 and China pushed green finance in the G20 during its 2016 presidency.

In the same year, a report by Germany’s finance ministry (BMF) found that substantial climate policy changes, such as a higher CO2 price, could wipe hundreds of billions of euros off its most important companies’ portfolios and inflict “severe losses” on the economy. The German government subsequently acknowledged the need for gaining ground in green finance and developing a more coherent policy approach. Its stated ambition is now was to become "a leading location" for green and sustainable finance endeavours in the future. To that end, it pledged a sustainable finance strategy and set up a Sustainable Finance Committee in 2019.

The strategy proposed a system to identify green investment opportunities, announced the reallocation of billions of euros in equities Germany holds in pension and welfare funds into green investments, and to make sustainable finance the priority of Germany’s diplomatic efforts in the G7 group of influential economies. Former Social Democrat (SPD) finance minister and current chancellor Olaf Scholz at the time said the strategy would bring a “decisive change of course for the financial sector,” in which climate action and sustainability would become the “leitmotif.”

Also the previous government's climate package from 2019 explicitly recognised the role financial policy plays for advancing or undermining climate targets and included concrete measures to make finance an active driver of more sustainable development, for example by issuing green state bonds or aligning public investment funds to sustainability principles. The finance ministry at the time already mulled screening all government expenses, currently about 360 billion euros per year, for ‘green expenses’ that could then be used to back the environmental credentials of the issued bonds.

In the government’s 2021 "traffic light coalition" treaty, the coalition of SPD, Green Party and Free Democrats (FDP) reiterated the ambition to make the country a sustainable finance leader, adding that this would also contribute to the overarching goal of financial stability. “Climate- and sustainability risks are financial risks,” the treaty said. The coalition said it would work towards establishing European minimum standards for the inclusion of ESG criteria in credit ratings and joint transparency and accounting standards that include ecologic and social aspects. To that end, the coalition renewed the Sustainable Finance Committee’s mandate to continue its work with new members as “an independent and effective” counselling body.

In 2020, the German government also announced the launch of so-called green "twin bonds" with a volume of about eleven billion euros in an attempt to lure investors into the sustainable finance market and raise funds for emissions reduction projects. The concept aimed to make the still marginalised green bond market more attractive by allowing especially larger institutional investors to switch to the conventional market if deemed necessary for liquidity purposes.

An analysis in the same year by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) found that public green bonds would be an ideal supplement to Germany's carbon pricing scheme, since the country's comfortable position on financial markets. It can borrow at very low interest rates, which affords Germany a comparative cost advantage to finance new technologies for the energy transition and boost climate-friendly exports, the researchers found. The government’s 2021 “Green Bond Allocation Report” then found that 11.5 billion euros were raised via green bonds in the previous year, allowing to offset most of the 12.3 billion euros spent on climate protection and environmental programmes in the preceding budget.

Apart from international competition for influence in the quickly expanding sustainable finance market, changes to international financial market regulation will also require a clear stance on greening finance. The European Commission's Sustainable Finance Action Plan has given rise to a common European classification system for sustainability, the so-called taxonomy, intended to provide policymakers, companies and investors with sound information on the impact of financial flows. The bloc's sustainable finance push boosts pressure on national regulators to respond, even though core questions such as whether the taxonomy will also apply to lending and thus impact the core business of banks have yet to be answered.

The BMF says a major obstacle in the creation of a concerted policy response so far has been the lack of a comprehensive and standardised database for climate-related risks and green investments. While abundant data on company emissions and different categories of green finance instruments are available (see glossary), these are often fragmented, incoherent and analysed in isolated case studies.

As of 2019, the most commonly used reference for green finance in German-speaking countries is compiled by the finance industry's sustainability body FNG, which also launched the region's first label for sustainable fund management. A similar sustainability metric for lending volumes has been under discussion for a while, but according to the Association of German Banks (BdB), too many definitions are still lacking to make the data operational.

In a response to an inquiry by NGO Bürgerbewegung Finanzwende published in January 2020, the ministry said it could not tell where Germany's largest supplementary pensions provider VBL has invested its money. VBL handles assets worth more than 25 billion euros of 4.7 million insured public sector workers and pays off more than one million pensioners per year. This means the BMF is in the dark about the share of climate-damaging investments made with public pension funds, a knowledge gap that bedevils the government's ambition to lead in sustainable finance. Moreover, the federal government’s investments are not at all subjected to sustainability criteria, the government-appointed Council for Sustainable Development (RNE) pointed out.

While state-owned development bank KfW has been a crucial contributor to the development of green finance in Germany as well as of the country's energy transition, the Energiewende, pioneered the country’s green bond market in 2014 and remains one of the most important international issuers of this credit instrument, activities are not comprised in an overarching green finance strategy.

Implementating the Paris Agreement and achieving international emissions reduction targets will require enormous financial investments. According to UN calculations, these could reach the equivalent of up to 15 percent of individual state budgets or up to about seven trillion dollars per year globally. The shift to renewable energy sources, electric mobility, digitalisation and other measures associated with the energy transition therefore needs to be backed by a parallel decrease in fossil fuel investments and a rise in the funding of low-carbon alternatives and energy-efficient technology through a systematic inclusion of the financial sector in climate policy.

State governments rely on banks, insurance companies, investment funds and other financial market actors to act in alignment with climate policies. For Europe, the goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030 is exacerbated by an annual funding gap of about 180 billion euros, the European Commission estimates. Germany alone would require additional investments of about 2.3 trillion euros to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 95 percent by 2050, equivalent to more than 70 billion euros per year, according to a study by industry federation BDI. Germany’s total federal budget for 2019 stood at about 356 billion euros.

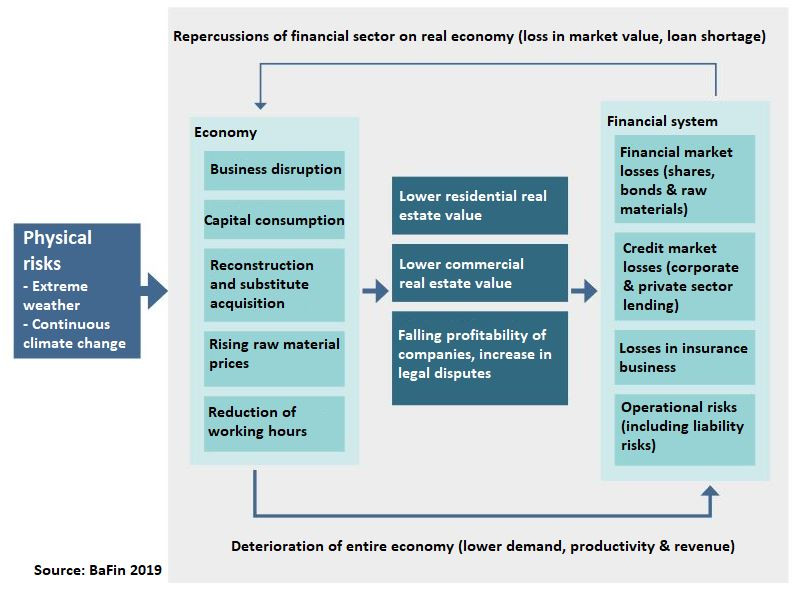

Global warming causes the financial sector faces two differents kinds of challenges at the same time. Financial investors not only face the immediate costs of more frequent extreme weather events but also a sudden devaluation of trillions in fossil assets due to unregulated divestment, as emissions reduction targets mean a large share of known reserves will have to stay in the ground. A mass withdrawal of funds invested in coal, oil and other fossil sources could let stock values plummet, turn balance sheets upside down and, by extension, deal a blow to pension schemes, insurers and government budgets around the world – a phenomenon known as the "carbon bubble".

A 2016 report by Germany’s finance ministry (BMF) assessed the impact of climate change and of possible political reactions to it from financial markets. The immediate effects of global warming on the financial system were considered negligible, at least in the medium run, but it found that an “orderly transition” to climate-neutral investments was necessary to avoid “severe losses” in the form of stranded assets, such as coal plants, in the case of abrupt carbon price rises that could destabilise the entire market. It also found that the value of the DAX, Germany’s most important stock market index, and the corporate bond market depend to a large extent on the business fortunes of high-emissions industries, especially producers of chemical and industrial goods and of cars. If companies were to internalise the costs caused by their greenhouse gas output through a higher carbon price, for example, this could wipe off more than 650 billion euros or five percent of company portfolios, even at still relatively low CO2 prices of 2016.

In order to minimise the disruptive effects of climate change and political responses to it on financial marekts, the Paris Agreement has stipulated a harmonisation of financial flows and emission reduction targets as one of its long-term objectives. This "shifting of the trillions" is meant to happen on two dimensions: First, by ensuring that investments do not run counter to emission reductions and, second, by raising capital for climate action measures. This implies systematically drying up financial flows that clash with reduction targets as well as a set of financial market reforms, such as a mandatory disclosure of climate-related risks, “Paris-compatible” investment criteria, adequate CO2-pricing schemes, stress-tests for credit systems, cutting fossil subsidies and decarbonisation roadmaps for industrial companies.

All of these measures are comprised in the concept of sustainable finance, which aims to ensure that the full impact of investments is understood and resulting risks are weighed against potential profits accordingly. Sustainable finance typically is based on so-called ESG criteria, which gauge the environmental, social and corporate governance dimension of capital flows. From a climate action perspective, the focus naturally rests on investments’ environmental aspects and is commonly referred to under the term “green finance”.

Asset management - The handling of financial investments by a professional agent

Best-in-class – Investment strategy that opts for funding leaders in given rankings in industries, technologies or categories

Carbon disclosure - Publication of climate-related activities by companies; spearheaded by NGO Carbon Disclosure Project and its disclosure leadership index

Corporate governance - The compliance of a company with laws, guidelines, voluntary agreements and other norms in its business conduct

Divestment – Withdrawal of capital from funds, equity or other capital assets from certain businesses or fields of operation, such as the coal industry

ESG –The Environmental, Social and company Governance dimension of business activities

ESG-Integration – The explicit inclusion of ESG-criteria in traditional risk analysis

Engagement – Long-term dialogue with invested companies to adapt investment decisions to ESG considerations

Exclusion criteria – Systematic elimination of certain investments or other categories, like companies or states, if they fail to abide by certain standard practices

Green Bonds – Bonds issued with the condition to finance environmentally friendly projects

GRI Standards - Globally used standard for sustainability reporting in finance launched by the Global Reporting Initiative Framework (GRI) since 1997

Impact investment – Investments made with the aim to make financial gains while also deliberately influencing ecologic and social developments

Integrated reporting - The inclusion of environmental and social impact information in company reporting to indicate financial and non-financial business aspects in parallel

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) - Screening of funds to exclude companies which generate a given share of their revenue with activities conflicting with given environmental, social or ethical values

Sustainability-themed funds – Financing of business areas or other assets that are associated with sustainability and have a connection to ESG-criteria

Norms-based screening – Evaluation of investments according to given international standards, such as the UN Global Compact, OECD guidelines or others

Finance regulators eager to streamline sustainability efforts as systematic overview is lacking

Financial regulatory authority BaFin has sought to streamline sustainable finance supervision. In reaction to a "call for action" made by the international central bank initiative Network for Greening the Financial Systems (NGFS), the BaFin published a bulletin on sustainability risks in late 2019 and invited financial market actors from all sectors to comment and submit position papers on the draft. Fund association BVI commented that while it recognised the need for better preparation, the draft would ignore difficulties like scarce data on compliance or rules that are too detailed and urged that national regulation should not exceed that in force in Europe.

Credit bank association Bankenfachverband noted that the paper's scope and degree to which it was compulsory were unclear, while American investment corporation BlackRock welcomed that it pursued a principle-based approach rather than setting hard guidelines for companies. NGO Germanwatch, on the other hand, said the proposal lacked concrete instructions on how to integrate sustainability principles in daily business and called for stress testing the financial companies' readiness to comply with international climate targets.

The consultation's results were merged in a nonbinding code of practice for climate-related and other ESG risks, which impact virtually all of its existing risk assessment categories. The government's finance sector watchdog said its guidelines would not alter existing regulation but rather aim at making sustainability more transparent as a risk factor. However, it said it expects regulated companies "to look into" corresponding risks, recommending they develop a "strategic approach" to the topic, as forthcoming EU regulation would require financial market actors to adapt their practices anyway.

The BaFin estimates that if climate change continues unchecked, resulting damages could reach up to 550 trillion dollars globally and wreck the business models of entire industries. This figure includes both the dangers lurking in the physical effects of climate change, such as extreme weather or crop losses, and the transitional risk, associated with disruptive policy decisions or changing consumer behaviour, which could be compounded by physical events. For example, the control authority estimates that the EU goal to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 will require a "dramatic" restructuring of the economy that is going to present individual sectors with "enormous challenges" for their financial stability.

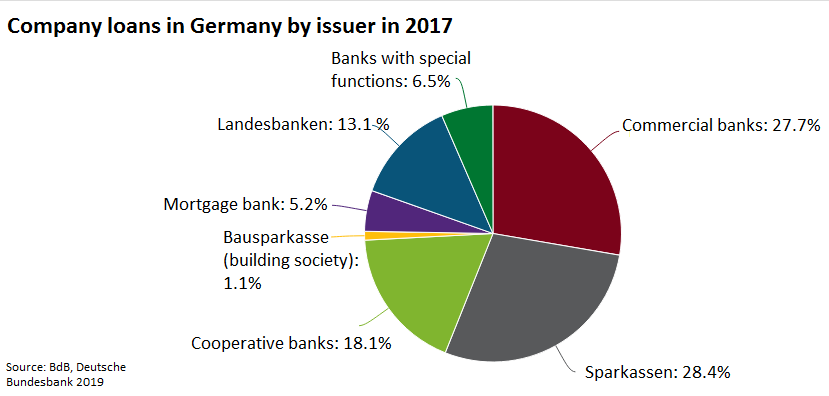

Banking in Germany features several peculiarities that makes it different from other industrialised countries. An important feature is the banking system’s three-pillar structure, which consists of the influential public Sparkassen/Landesbanken and the cooperative Volksbanken as the first two pillars and the purely commercial banks as the third. With aggregate assets of about 1.2 billion euros, they rival the biggest commercial banks and reach far more customers across the country thanks to their dense branch network. The public and cooperative banks have a dense and locally rooted branch network and thus stay well-informed about the business prospects of the companies they fund. Together, they account for nearly two-thirds of company credits issued in Germany.

Germany’s financial sector is among the largest in the world and very exposed to international markets. As most businesses rely on bank credits for their funding rather than on equity, it is an important pillar for the country’s general economic stability. With a total value of 111 billion euros, financial services contributed about four percent to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017 and employed about 1.2 million people, according to government agency Germany Trade & Invest.

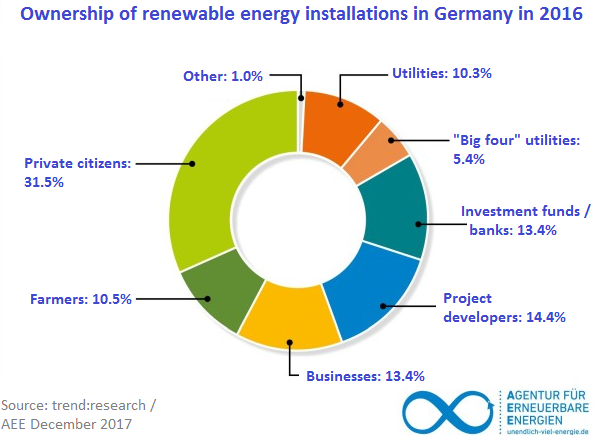

However, the inclusion of ESG criteria was spearheaded by a range of small and specialised financial institutions connected to the ecologic movement and, notably, the church, which helped finance the Energiewende’s early stages and until today remain relevant best-practice examples for sustainable finance. The number of green financial products on offer ballooned with the introduction of Germany’s Renewable Energy Act (EEG) in 2000, funded for the most part by public and cooperative banks, an analysis by the University of Stuttgart found. By 2018, a total of 271 billion euros had been invested in wind power, solar power and other clean energy sources, according to industry group Renewable Energies Agency (AEE).

The vast majority of these investments was made by small investors through specialised mediators rather than by larger banks, investment funds or other institutional actors. While individual citizens, cooperatives and small and medium-sized companies own more than half of Germany’s installed renewable energy capacity, banks and funds accounted for just over 13 percent in 2017, the AEE found.

However, despite their key role in financing energy transition projects, the Stuttgart University analysis as well as an industry survey by the consumer protection organisation Verbraucherzentrale.NRW found that public and cooperative banks so far remain largely unaware of the green finance market potential and stick with tailor-made local projects. A more concerted effort by publicly owned financial institutions could allow Germany to leapfrog development and quickly spread green finance principles across the entire sector, according to NGO Finanzwende.

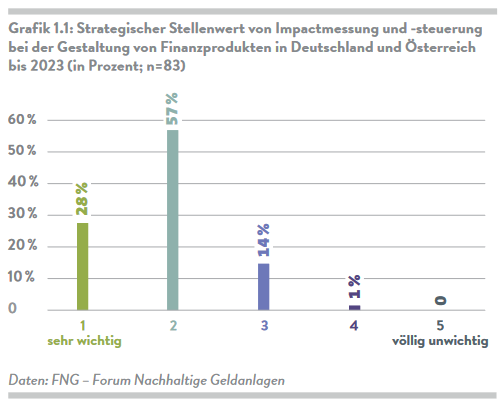

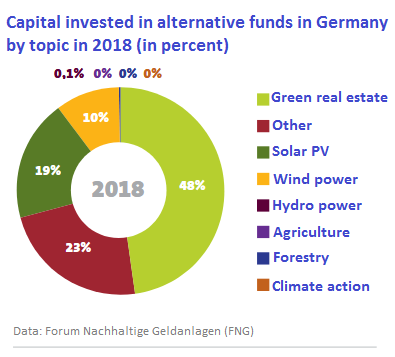

The growing market volume for green products and uncertainty over regulatory intervention has fanned calls in Germany’s financial sector to clarify future guidelines and risk assessment metrics. The industry has started to embrace sustainability on a broader basis in recent years, with sustainability association FNG noting that key industry actors and large investment funds helped boost investment volumes by almost 50 percent in 2019. The interest has been bolstered by recurring analyses that found no long-term negative impact on investment profitability if ESG criteria are applied.

The launch of Germany’s Green and Sustainable Finance Cluster (GSFC) and the associated Hub for Sustainable Finance (H4SF) in 2018 showed that market actors are eager to develop an adequate infrastructure and regulatory framework for sustainability in finance. The GSFC started as a joint initiative by government sustainability council RNE and stock market operator Deutsche Börse Group and soon gained support from leading commercial banks and insurance companies, including Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank and Allianz, which are the largest holders of assets under management in the country.

Sustainability initiatives by financial actors have often been accused of being mere greenwashing vehicles that are far from being as ecologically effective as they are advertised, however. NGOs like Urgewald have repeatedly rebuked commercial and public finance actors for upholding adverse investments while otherwise flaunting a clean slate. So far, there exists no legal mechanism for Germany's financial supervision authority BaFin to hold issuers of misleading advertisements to account, let alone to penalise them for ignoring sustainability standards.

Germany scored poorly in an international ranking evaluating the management of climate and environment-related risks by NGO Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) of financial and non-financial companies. Only nine German companies out of 8,000 analysed globally received CDP's most favourable rating, indicating that they actively work on making their carbon footprint more transparent and develop strategies to reduce it. The top-ranking country Japan boasted 38 companies in CDP's so-called A-list and Germany's neighbour France 22 firms in the highest category. More than half of the total German 200 companies included in the ranking failed to provide adequate data to participate, CDP noted.

The participation of ordinary citizens and small investors is seen as vital for the sustained success of green finance, both due to the direct financial flows to climate projects and the pressure this exerts on credit providers to come up with corresponding financial vehicles. Most German citizens, however, are rather sceptical towards financial markets in the first place and investing in equity and other capital markets is far less common in Germany than it is in the US or the UK.

While the share of shareholders across the population stood at 25 percent in the US and 23 percent in the UK in 2016, the figure was merely 6 percent in Germany, the Association of German Banks (BDB) reported, and physical currency savings or bank deposits account for a much larger share of households’ financial assets, according to OECD data. About 40 percent of the official 6 trillion euros in monetary wealth held by Germans in 2018 rested in low-interest cheque or savings accounts, the BDB added. A possible explanation is the mandatory public retirement insurance system in place in the country, a pay-as-you-go system in which the vast majority of the workforce is enrolled, making a reliance on market-based pension schemes less attractive.

A survey by the University of Kassel, however, suggested that the market for private investors for sustainable financial products in Germany covers about ten percent of the population, around seven million people. About 40 percent of private investors are interested in such products but less than five percent so far have considered ESG criteria when actually carrying out an investment. Respondents stated that the main reason for not investing in corresponding products was a lack of information and scarce consultancy by their banks.