2026 set to shape the future of the EU’s climate and energy architecture

After a year marked by the rollback of existing climate rules – from weakening deforestation regulations and company sustainability reporting obligations, to postponing emissions trading in transport and buildings – the EU will begin looking forward in its climate debates in 2026. Negotiations on the European Union’s next long-term budget, alongside talks on climate and energy rules for the post-2030 period, are set to take centre stage.

“After adopting the 90-percent climate target for 2040, the debate will shift towards what this means for individual sectors in the post-2030 policy framework and how to mobilise investments,” said Linda Kalcher, executive director and founder of the Brussels-based think tank Strategic Perspectives.

Similar to the 2021 “Fit for 55” package of energy and climate reform proposals to reach the 2030 target of reducing emissions by 55 percent, the European Commission is expected to present a follow-up package next year. In the third quarter, it plans to propose reforms to key rules and regulations, from the Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the renewable energy framework to the future of national climate targets currently governed by the effort sharing regulation.

Climate policy has given room to other priorities over the past years, and if current efforts to weaken policies to avoid and reduce greenhouse gas emissions persist, the EU risks locking in an energy and climate architecture that lacks the necessary ambition to sufficiently contribute to the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to well below 2 °C.

Emissions trading under pressure

Emissions trading, one of the most – if not the most – crucial climate policy instruments, will be a key focus. The EU has set a price on CO2 emissions to incentivise the right investments by companies to shift to a climate friendly society.

EU countries recently decided to delay the start of the new ETS 2 for transport and building emissions by one year to 2028. Several governments worried that a uniform CO2 price across the EU would lead to steep increases in petrol, fossil gas or heating oil costs, which would hit low-income households in poorer member states especially hard, as these often lack the resources to switch to climate-friendly alternatives. Governments said this could fuel public resistance to climate action.

However, experts warned that further changes to the system loom, especially if the EU fails to alleviate governments’ worries. Countries like Poland had called for the start of the system to be delayed by several years, and could easily make the same arguments half a year from now.

“Of course, this will be discussed again,” said Brigitte Knopf, founder of the think tank Zukunft KlimaSozial.

Similarly, the original ETS for the energy and industry sectors is facing headwinds. Industry has called for adjustments that would weaken the system, and German officials have proposed extending the ETS by several years. Under current rules, the emissions cap is set to reach zero by around 2039, so no new allowances would be given out from that time, leaving only existing unused allowances in the market. The European Commission is set to review the ETS by summer. That review, together with the package to reach the 2040 climate target, will present key moments to kickstart reforms to the system.

The importance of 2027 as a “super-election year” in the EU should not be understated.

Experts have called on countries to ensure that the ETS is preserved.

“If ETS-1 is substantially watered down in 2026, without massively strengthening other pillars, the whole structure risks collapsing, tanking overall clean investments,” Philipp Jäger, senior policy fellow at the Jacques Delors Centre think tank, told Clean Energy Wire. Germany and other EU governments that still back climate objectives should do more to safeguard it, he said.

However, election dynamics could spell further trouble for ambitious climate policy decisions next year. In 2027, voters in major European economies - including France, Italy, and Poland - head to the polls.

“The importance of 2027 as a 'super-election year' in the EU should not be understated,” said researcher Kalcher. “It brings additional volatility,” as countries might struggle to position themselves ahead of elections, she said.

EU budget, industry competitiveness, and the clean transition

The EU’s climate and energy agenda in 2026 will also be marked by a continued focus on industry competitiveness, and a general drive for independence.

In its 2026 work programme, titled “Europe's Independence Moment”, the European Commission has said that the EU must “shape its own future” on wide-ranging issues like climate action, security and defence, the development of its democracy or jobs and a modern economy.

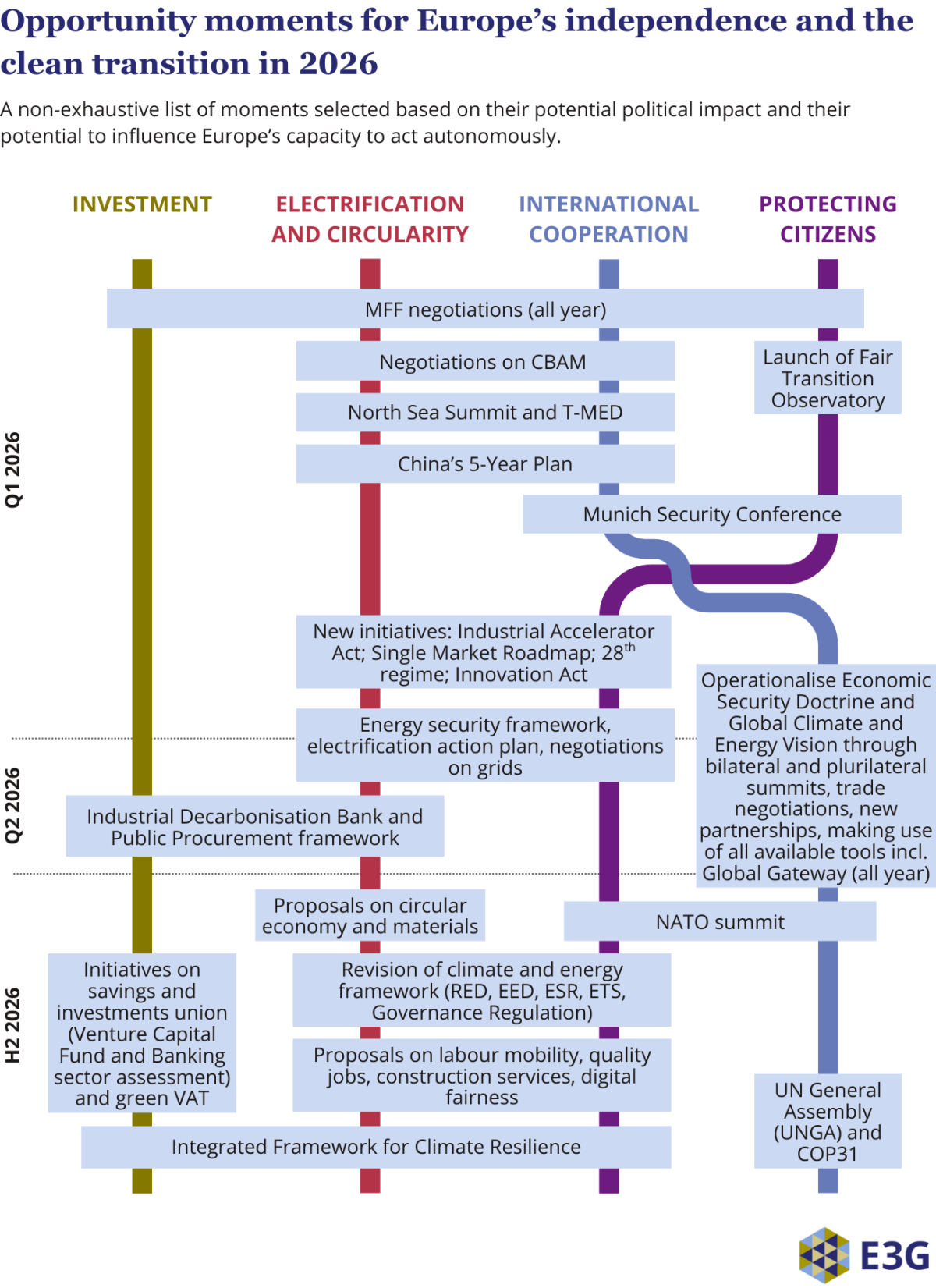

Europe’s ability to do so will be influenced by several crucial political dynamics, said think tank E3G in a preview article for 2026. Europe’s strategic dependencies leave it exposed to foreign influence and interference, while an increasingly fragmented European Parliament lacks one stable majority, which makes the institution’s positions on issues less predictable.

The think tank sees four challenges for the EU’s independence bid:

- Rebuilding Europe’s financial autonomy and capacity to invest

- Harnessing electrification and circularity as levers for strategic autonomy, competitiveness and energy security

- Protecting citizens while visibly delivering tangible benefits

- Diversifying partnerships and deepening international cooperation

Throughout next year, the EU institutions will negotiate the Commission’s draft for the union’s next long-term budget for the period from 2028 to 2034. The Commission has proposed dedicating 35 percent of the almost two-trillion-euro budget to climate and environment objectives, which NGOs have criticised as too little. E3G emphasises that the EU must also set the right framework to rebuild investor confidence and improve its capacity to mobilise private capital.

Researcher Kalcher said Europe should make sure it invests domestically, instead of paying third countries for imports. “With the EU budget on the table and the proposals on phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and industrial decarbonisation coming, it’s high time to invest into Europe instead of sending money to the US, Russia or Qatar,” she said.

Europe remains heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels, and the transition to renewables is seen as an opportunity to reduce these dependencies overall.

E3G calls on the EU to push for a more circular economy in 2026, as this would lower imports and energy use, “creating new markets for affordable, European recycled materials and products.” The upcoming Industrial Accelerator Act, Circular Economy Act, Innovation Act, and revised public procurement rules are expected to be key developments in this regard next year.