Can Salzgitter cut Germany's CO2 emissions with low-carbon steel project?

Salzgitter has developed a “technically feasible but not economically viable” concept to replace the fossil fuels used in conventional steelmaking with a gradually rising share of renewable hydrogen. The company has dubbed the project “SALCOS” (Salzgitter Low CO2 steelmaking). The company says the project can only be realised with substantial public support for the initial investment – around 1.3 billion euros for the first stages alone – and new regulations to make the resulting low-CO2 steel competitive in comparison with conventional CO2-intensive steel. Salzgitter CEO Jörg Fuhrmann said in April he was confident that policymakers will provide the support necessary to realise the decarbonisation project.

The entire Salzgitter Group, which comprises more than 100 companies, recorded sales in excess of nine billion euros in 2018, and employs 25,000 people.

The steel industry is one of the world’s largest carbon emitters and accounts for around seven percent of global emissions. But decarbonising the sector has barely begun, and it remains one of the most difficult parts of the energy transition. The industry uses carbon to smelt iron ore and, in existing processes, CO2 emissions are unavoidable.

But the idea of replacing fossil fuels with green hydrogen in steelmaking has recently been gaining traction. Swedish power company Vattenfall presented plans to replace coking coal with fossil-free electricity and hydrogen in cooperation with Swedish steelmaker SSAB and ore miner LKAB. Germany’s ThyssenKrupp has also said it wants to use hydrogen, and Indian sector giant Tata Steel has said it plans to develop the largest green hydrogen cluster in Europe in the Netherlands in a major step towards becoming carbon neutral.

Clean Energy Wire spoke to Volker Hille, who is head of corporate technology at Salzgitter Group, about the prospects and potentials of the company's SALCOS (Salzgitter Low CO2 steelmaking) hydrogen project.

Clean Energy Wire: Could you describe your proposed trajectory towards a low-carbon steel production based on hydrogen in Salzgitter?

Volker Hille: We already have an electrolyser in operation on our factory premises. This pilot project named GrInHy (Green Industrial Hydrogen) is a high temperature electrolyser from Dresden start-up Sunfire. With a capacity of 150 kilowatts, it is the largest of its kind in the world. In addition, we recently agreed on the installation of a follow-up project – GrInHy2.0 – which will be five times the original size. So we are gradually approaching the megawatt level. These are our high-temperature electrolysis (THE) activities.

We are also in the process of realising the project WindH2. This will involve seven wind turbines on our premises or nearby, together with a 2 megawatt PEM electrolyser. Both projects should be completed by next summer. The hydrogen produced by both projects is not intended to be used in metallurgy, but to replace “grey” hydrogen in our existing finishing processes, where steel coils are being annealed in a hydrogen atmosphere. Currently, the needed volumes are supplied from external sources, which generate hydrogen via traditional steam reforming of natural gas.

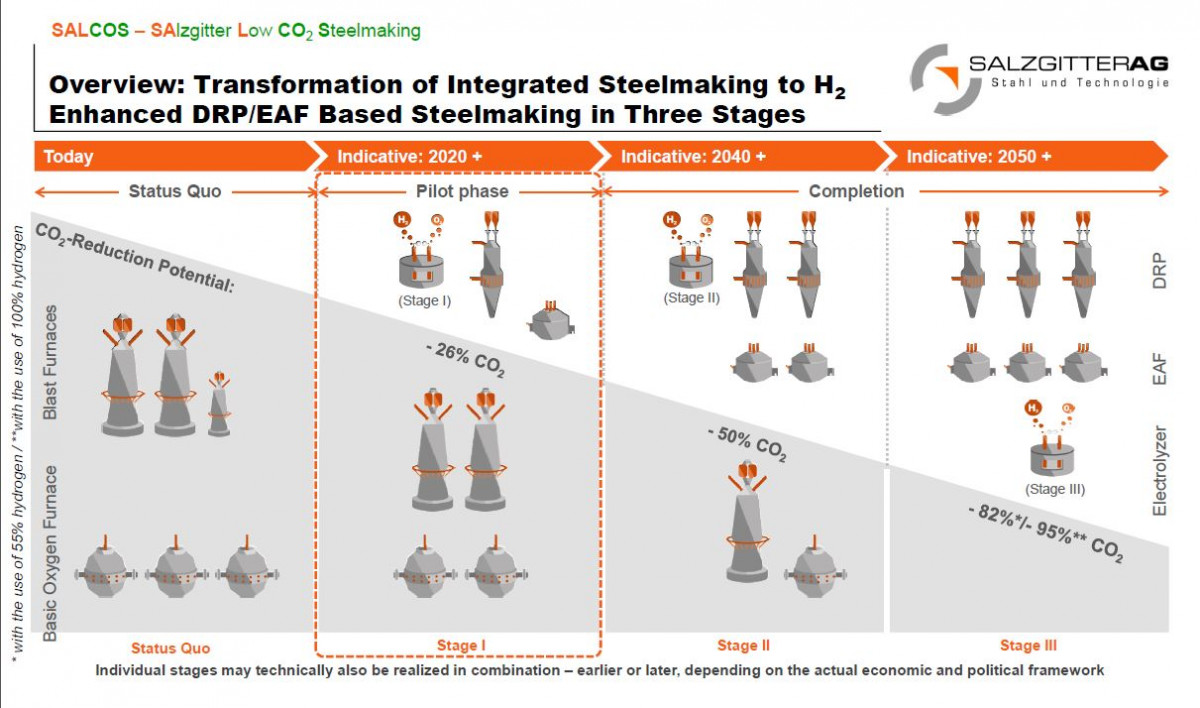

That’s what we’re doing already today. In contrast, our proposed SALCOS project involves the large-scale conversion of metallurgy itself – which is the first step of our process chain – from carbon-based fuels to renewable hydrogen. The blast furnaces operated today are - and principally always will be – coal-based. Hence, our general plan is to gradually replace them with a different technology called “Direct Reduction”. This runs on natural gas, and offers the possibility to incrementally switch the fuel to green hydrogen. Downstream steelmaking would be done in so called “Electric Arc Furnaces”, replacing the existing converters.

We can’t yet put a date on the project because we’ll need financial support to realise it. But from a purely technological viewpoint, the first stage of this massive conversion project could see the light of day by 2025.

[This video explains the SALCOS project in simple terms:]

Simply put: We can only realise the SALCOS project if we can make sure that we will be able to sell our low-carbon steel afterwards. Its competitiveness will depend on several prices. Firstly, the carbon price – it would help if it is as expensive as possible, because we want to replace it. Secondly, we will need natural gas. Thirdly, we will also need a lot of electricity, especially for electrolytical hydrogen production and electric steelmaking. All of these factors will combine and cause a change in costs in comparison to the conventional method, and this change will surely not be in the right direction.

The question is: How can we realise such a project in a highly competitive market? We’re under constant pressure from non-EU and overseas rivals, which are neither inclined nor obliged to put the same effort in climate-friendly production. The SALCOS steel will be exactly the same as before, except it will be decarbonised. How do you sell that?

At present, we simply don’t have the necessary framework conditions that enable us to say: “We will march in this direction because we are certain that we can run it economically and won’t risk the existence of our company in the process.” This is a clear danger, because we’re really talking large-scale here – we don’t want to build another pilot project, and we simply don’t need one, because we’re certain the technology will work.

All we’re saying to politics and society is: Give us a chance to realise this project to take advantage of the great CO2 avoidance potential, which will be starting at 2 million tonnes of CO2 per year for the first implementation stage, reaching a final level of roughly 7.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year for the complete conversion of our works to the new production route, which equals a reduction of 95 percent compared to current levels. This is really deep decarbonisation! The global perspective of our approach has also to be considered, as steelmaking is responsible for 7 percent of all man-made CO2 emissions (which equals 30 percent of all industrial emissions).

Please note that only the first stage of SALCOS will require an investment of about 1.3 billion euros in new plant equipment, illustrating the need of substantial public funding.

So you need both: Financial support for the initial investment, and also a change in framework conditions to sell the low-carbon steel afterwards?

Yes, absolutely, because we definitely don’t want to become permanently dependent on subsidies. European regulations won’t allow it anyway. As I said, initial funding for the installation would be necessary, and we’ll put a respective application to the European Investment Fund once it’s up and running. But the new technology will have to be permanently operated afterwards. The question is: Will our customers, e.g. VW, want to buy our low-carbon steel sheet? Will they have an advantage by using low-carbon instead of conventional steel?

Since you bring up VW as an example – the company has announced plans to go entirely carbon-neutral by the middle of the century. Don’t you think company announcements like these will create the necessary demand for your low-carbon steel?

Let’s hope they will result in the possibility to create it! I guess VW has similar problems to ours: They also need a framework supportive to decarbonisation. At present, most clients are economically not able to take into account the CO2 balance of steel in their purchasing plans. European steel already causes fewer emissions than, for example, Chinese, Indian or Ukrainian steel, but using European material instead is not yet stimulated by the political framework. In essence, steel users like VW or Daimler need to have an incentive to deploy this low-carbon product. But it simply does not exist today. It’s also important to keep in mind that in industrialised countries, only around 20 percent of steel is used by the car industry – most of it goes into infrastructure projects such as steel girders used in building construction, where it often has to compete with concrete or other materials.

There are alternative proposals to clean up steel production with carbon capture and usage, for example by ThyssenKrupp. Do you believe we will have several clean steel technologies in the long run, or will one method “win” over the others?

We firmly believe that the use of hydrogen is the future for steel production. The problem with carbon capture and usage (CCU) is that it is very energy-intensive and offers only a “single-loop” CO2 recycling which stores it only for a limited period of time. We also looked at this approach, but we realised that it is not realistic. The basic problem is that CO2 does not contain any usable energy. The only way to transform it into a fuel – or use it for any other purpose – is by adding a lot of energy and hydrogen. Even if you use metallurgical gases that still contain some hydrogen, you will still have to add a lot of hydrogen, which will eventually have to be made using electrolysis, otherwise the resulting product won’t be green at all. It’s much more efficient to use the hydrogen directly in steel production – you need between four and five times less energy compared to CCU.

ThyssenKrupp has already said they are also heading for hydrogen use, but without giving too many details. They have also said they want to continue their Carbon2Chem project. But in the long run, the two approaches are incompatible because if you run your entire steel production on hydrogen, there is no CO2 left to use.

I believe the carbon-to-chemicals approach is much better suited to other industries such as cement. There, it makes absolute sense because producing cement will always result in CO2 emissions, no matter what fuel you use (as the CO2 originates directly from the limestone mineral CaCO3, essential for cement), meaning the sector will necessarily have to apply CCU in the long run. Cement is also a huge industry and can produce enough carbon to supply the chemical industry – we don’t need carbon from steel production for this purpose at all.

We are the only ones who pursue such a large scale CDA (Carbon Direct Avoidance) project like SALCOS with such emphasis – we are frontrunners. Once we have it running, the technology needs to be deployed in as many other steelmaking locations as possible. It doesn’t make sense to save a few million tonnes of CO2 in Salzgitter alone. This must be applied by everybody in our industry. For steelmaking, this is the right approach.