Europe’s cities step up efforts to fight heat, drought, floods

The world's largest floating office imperceptibly rises and falls with the tide in Rotterdam’s Rijnhaven harbour basin, where the Rhine-Meuse delta meets the North Sea. Designed to be largely self-sufficient and “future proof”, it runs on solar power, uses river water for heating and cooling, and has a green roof to absorb rainwater. Built mostly from European timber, it is designed to be dismantled and reused.

Its most striking feature, however, is that it sits on water – rising sea levels and floods pose no threat. The Floating Office Rotterdam is one of many solutions that architects, urban planners, local officials and climate experts are developing to make the places where people live, work, and recreate more resilient to the impacts of climate change.

Rotterdam is a pioneering city when it comes to climate resilience: for over a decade it has built water squares, green spaces, dykes, and storm barriers to fend off rising seas, torrential rain, heatwaves, and droughts.

“It’s a matter of self-interest,” said Chantal Zeegers, the city’s vice mayor, at the European Urban Resilience Forum (EURESFO) in June. With around 80 percent of Rotterdam below sea level and Europe’s largest port on its shores, the city is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Adaptation is essential to keep society and the economy functioning.

Europe | "We are gambling with the risks"

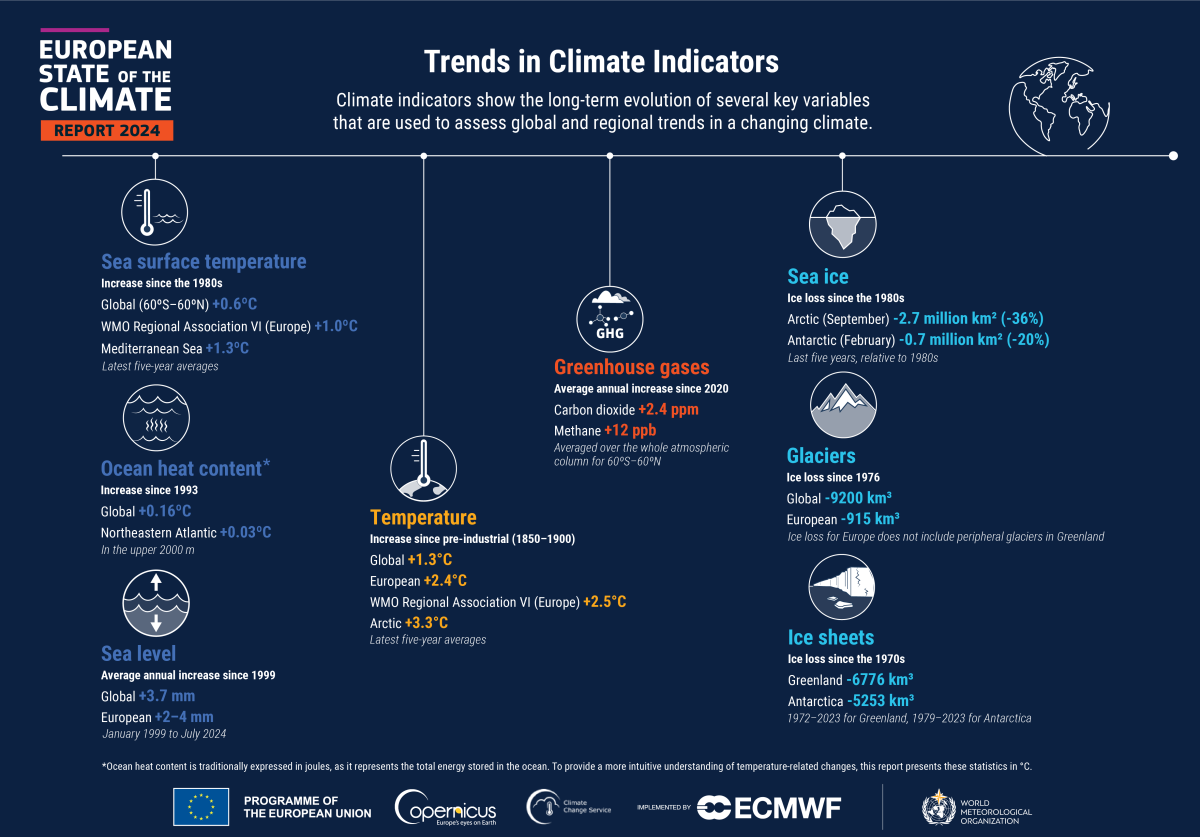

Europe is the world’s fastest warming continent, with temperatures increasing at more than twice the rate of the global average. Devastating floods in Spain, raging wildfires in Greece, and destructive droughts in Poland highlight the urgent need to prepare for worsening impacts, alongside cutting emissions.

“We are gambling with the risks we are facing,” said Wolfgang Teubner, head of ICLEI Europe, a network of regional governments promoting sustainable development. As some authorities and businesses hesitate to build resilience, damage is inevitable. “One way or another, we will pay the bill.”

Copernicus." />

Copernicus." />Around 75 percent of Europe’s residents live in urban areas, making investment in urban resilience particularly impactful, according to Blaž Kurnik, who leads the Climate Risk and Resilience unit at the European Environment Agency (EEA), an independent EU advisory body. “If you increase resilience in urban areas, then you're capturing quite a significant share of the population.”

Yet change is slow. “We’re trying to change habits that are well established and have worked for a very long time,” ICLEI’s Teubner told CLEW, alluding to towns which have spent funds rebuilding damaged infrastructure without building in much-needed climate resilience. “Unfortunately, it needs time and patience to change these because we’re addressing a problem that has a very long time horizon where negative impacts come only with a delay.”

Teubner is worried that society has not quite grasped the scale and severity of climate change’s impacts, and the urgency needed to avoid crossing tipping points. “It’s like trying to stop a car driving at 200 kilometres per hour – you’ll see how long that takes you. The more you delay, the more likely it is you’ll have a bad crash, because you don’t have enough room for manoeuvre anymore.”

Paris | Providing shelter from deadly heat

Of all extreme weather events that pose a danger to human health, heatwaves are the deadliest. In Europe, over 175,000 people die every year from heat-related causes, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

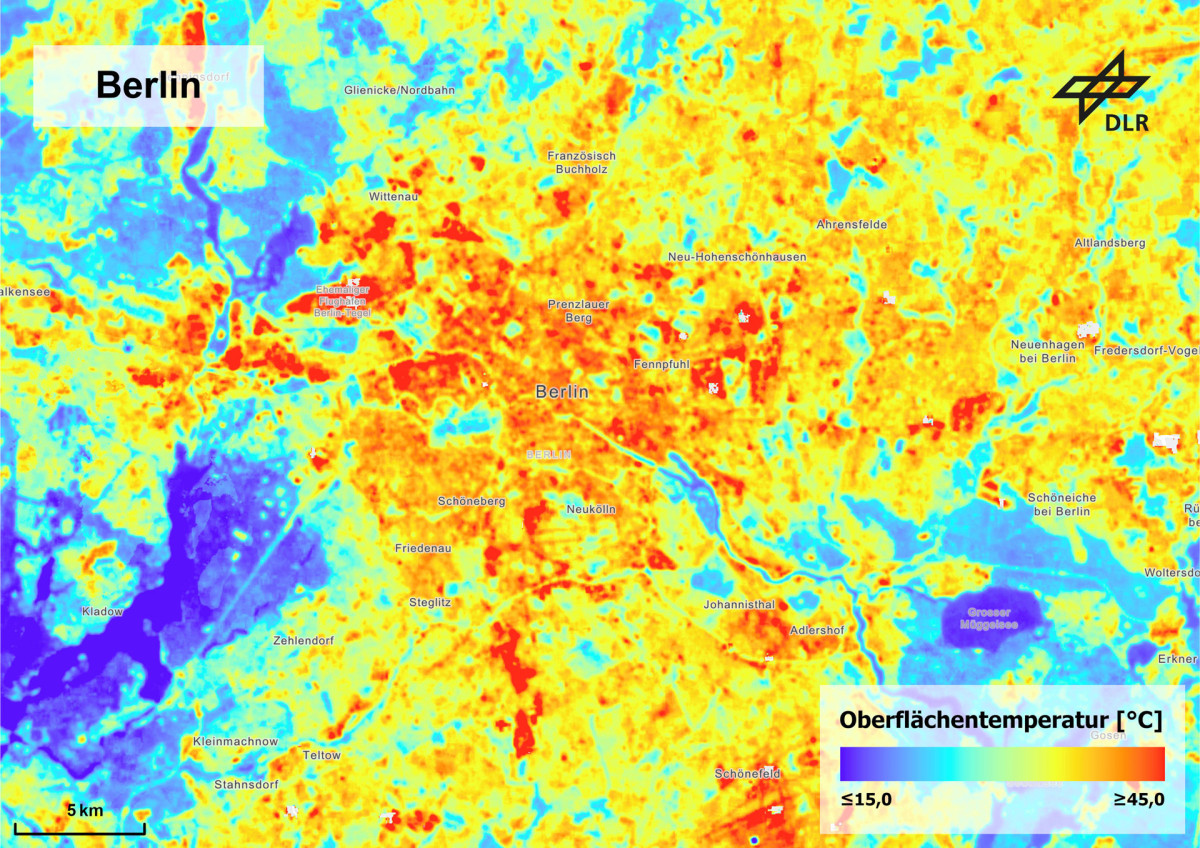

Urban areas are particularly exposed: cities are routinely four to six degrees warmer than surrounding areas. Concrete roads, pavements, and buildings absorb and retain the heat, creating so-called urban heat islands which strain social care services and buckle roads and crack bridges. Nearly half of city hospitals and schools are in areas exposed to strong urban heat island effects. This problem affects homes too, with surveys showing that one in five households in the EU feel unable to cool their homes properly.

We know that we will have extreme heatwaves, so we’re trying to plan for this.

Paris is among the cities taking measures to cope with the heat, partly by increasing public green space. This can noticeably reduce temperatures naturally, make places more attractive, improves biodiversity, and stems heavy downpours which can overwhelm drainage systems.

“We know that we will have extreme heatwaves, so we’re trying to plan for this,” Marie Rouaux, adaptation project manager at the City of Paris, told CLEW. The city modelled what would happen if temperatures reached a scorching 50°C, and is gearing up for it.

Paris set the aim of planting 170,000 trees by 2026, but finding suitable spots can be difficult given the city’s density. Simply planting trees in the hottest areas is not possible if there is a risk of the roots damaging subterranean infrastructure, like the city’s metro system, sewage or gas pipes. Yet information on what lies below ground is often outdated, restricted or classified.

The city’s experts are also at odds on whether to prioritise native trees, better for local biodiversity, or species from southern France, better adapted to hotter climates. Presently, a mix seems to be the answer.

Then comes the question of where to source the trees from. “Even as nurseries become more professional and efficient, many still struggle to secure a stable market footing,” said Tim Van Hulle, president of the European Nurserystock Association, a group representing tree nurseries across the continent.

And finally, there is the issue that trees take years to provide significant shade. The city is therefore experimenting with temporary solutions such as shading furniture in parks and squares. Rouaux’s team is testing locations, ease of installation, and how to fit designs into Paris’s historic architecture. Thinking all of this through is key: “Obviously the shade moves during the day, so if you put benches under it, at some point they will be exposed,” Rouaux explained.

Paris is also expanding its cooling network, which uses water from the Seine instead of air conditioning, to bring temperatures down in over 800 buildings. It has also pledged to retrofit all its schools and kindergartens by 2050, and created a “cool islands” network where residents can take shelter during heatwaves.

There is no silver bullet solution for climate adaptation, and poor implementation of good ideas can result in bad outcomes.

“Upscaling solutions that have positive effects but very few trade-offs is very difficult,” EEA’s Kurnik said. “Even the most optimal of solutions like green spaces in cities can be wrongly implemented.”

Experts warn of “maladaptation” – measures that worsen consequences rather than reduce risks. For example, widespread use of air conditioning can actually make outside temperatures hotter, as the cooling units release heat, worsening the urban heat island effect.

In some cases, global warming might result in solutions backfiring. Planting fast-growing but highly flammable trees may increase fire risk as drought spreads, while shallow-rooted or heavy-canopied species are at higher risk of being damaged – and causing damage – in intensifying storms. Some species may also worsen allergies as pollen seasons extend with warmer winters.

City officials point to governance as key to successful adaptation, recalling a project in Greece which covered a school’s rooftop with vegetation – which dried out when administrators switched off irrigation during the summer break. “One of the main challenges with adaptation measures is that every time you do something new, someone has to take care of it,” said Paris’ Rouaux.

Spending billions on new housing, roads or neighbourhoods makes little sense if projects are likely to be washed out by extreme weather events. Some authorities, therefore, are embedding resilience into their planning, ensuring that new projects can withstand and adapt to future risks. This concept is known as resilience by design.

In Barcelona’s metropolitan area, officials are embedding this resilience concept into all new public work, “out of professional and institutional responsibility,” said Albert Gassull, who heads the public space services department. Gassull led the process of introducing a protocol setting sustainability criteria for projects ranging from archives to promenades.

The approach starts by questioning whether new construction is needed at all. Where possible, existing spaces are to be converted and used more efficiently. New projects must use low-carbon materials, minimise energy use, and integrate clean energy sources to reduce emissions through their lifetime.

Additionally, projects are designed to withstand future climatic conditions while ensuring that they contribute to good water management, biodiversity and health. For example, the protocol stipulates mechanisms to reduce water use and improve water retention; it requires species to be catalogued to ensure biodiversity is preserved and stimulated; and it sets rules to limit air and noise pollution as well as requiring a minimum amount of green space.

“It’s a holistic vision; it’s not either or when it comes to solving [these] issues,” Gassull said. Importantly, the protocol must be integrated into the design of public spaces and buildings from the outset. Its criteria serve as starting points that must be considered before any project decision is made.

This future-conscious approach is not the norm, yet his office has been successful in getting some municipalities in Barcelona’s metropolitan area on board: “We even developed a game based on the protocol where officials could use its criteria to design more – or less – sustainable spaces,” Gassull said. Some councils have now asked to adhere to the protocol, which so far was only mandatory for projects under the jurisdiction of Barcelona’s metropolitan area.

EU | The solutions are there, now it's time to act

While at higher risk, the European Union has made progress in the journey to climate adaptation, the EEA’s Kurnik highlighted. “Climate change impacts are accelerating, there are more and more big events happening, economic losses are increasing, and the number of fatalities due to extreme events are increasing too, mainly due to heatwaves.”

DLR (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)." />

DLR (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)." />The EU is preparing a climate resilience and risk management strategy, due at the end of 2026, aiming to establish a more ambitious and comprehensive approach to climate preparedness. It is expected to introduce legally binding rules, economic instruments and monitoring tools to harmonise risk assessments and coordinate action.

“I do not think there is any more need for more types of solutions – they can be useful, but the techniques are already there,” said Arnoud Molenaar, former chief resilience officer in Rotterdam. “There are loads of examples, we just have to come up with implementation programmes and find ways to finance this. Often this means using existing money in a smarter way.”

Rotterdam | Getting citizens involved

In Rotterdam, residents are in the middle of the annual tile-popping contest, removing tiles from driveways or the front of their homes and replacing them with greenery. The tiles are collected by a “tile taxi”, crushed and recycled for use in road repairs, for example.

The contest began during the global pandemic in a competition against Amsterdam, as a way to improve rainwater drainage and boost biodiversity. It has since grown into a national event.

“We have to de-pave our cities and replace concrete with more green,” said Molenaar. “That can be done in public spaces, but in the case of Rotterdam 60 percent of the area is not public but private. Therefore, we need citizens and housing corporations to also take measures to make the city as a whole more climate resilient.

“It’s a fun thing, and on a national scale the result now is that millions of tiles have been removed and citizens are part of the move to become more climate adapted,” he added.