Germany's Climate Action Law

Germany’s Climate Action Law is the core of national climate policy in the country. It enshrines greenhouse gas reduction targets into law, and stipulates that each new government must present a programme of measures to ensure the targets are met.

The targets are derived from the country’s obligations in the EU. As part of the European Union, Germany is obliged to reach its country-specific climate targets under EU commitments, and do its part to ensure the union reaches its joint targets.

[Find a translation of the German climate law by the economy ministry here.]

Until 2019, Germany did not have a climate law like the UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act – one of the world’s earliest comprehensive framework laws on climate. Instead, Germany’s climate action policies were embedded in a multitude of national laws, government programmes, EU regulations and international agreements. Several German states have their own climate action laws.

Germany’s national climate targets had been specified in government policy programmes in 2007 and 2010 and have been upheld by every government since. They were reinforced with Germany’s Climate Action Plan 2050, the country’s long-term climate action strategy.

Then-environment minister Svenja Schulze aimed to make these targets legally binding – also for future governments – and better translate EU goals into national regulation. She presented the first draft of a German Climate Action Law in February 2019. It was, however, heavily criticised by many in the coalition, and for some time there were doubts Germany would get a major framework climate law. Instead, critics within the government called for only a policy programme with climate action measures for each sector.

However, amid growing public anger and frustration at the devastating effects of climate change following heat waves, droughts and the Fridays for Future student climate protests in 2018-2019, the government in October presented the law following months of internal negotiations.

Since it first entered into force on 18 December 2019, the law has undergone several key amendments. The latest reform in 2024 weakened the law, abolishing the requirement that the government introduces immediate action programmes if a sector exceeds its annual emissions limit.

German lawmakers in summer 2021 adopted a crucial reform, introducing more ambitious greenhouse gas reduction targets and details on post-2030 goals. This became necessary after a landmark ruling by the Constitutional Court on 29 April 2021. Germany's highest court ruled that the law was insufficient because it lacked details on emissions reduction beyond 2030. Following this ruling, the government greenlighted the necessary legal changes to speed up the country's bid for climate neutrality, aiming to hit the goal five years earlier in 2045.

Map overview of European countries which have implemented climate action laws. Source: Ecologic, 2024.](/sites/default/files/styles/paragraph_text_image/public/paragraphs/images/ecologic-institute-climate-laws-europe-status-sept-2024.jpg?itok=V1XZbnVL)

General purpose of the law

- Guarantee that Germany fulfils national and European climate targets “to provide protection from the effects of global climate change”

- Law is based on the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and possibly to 1.5°C

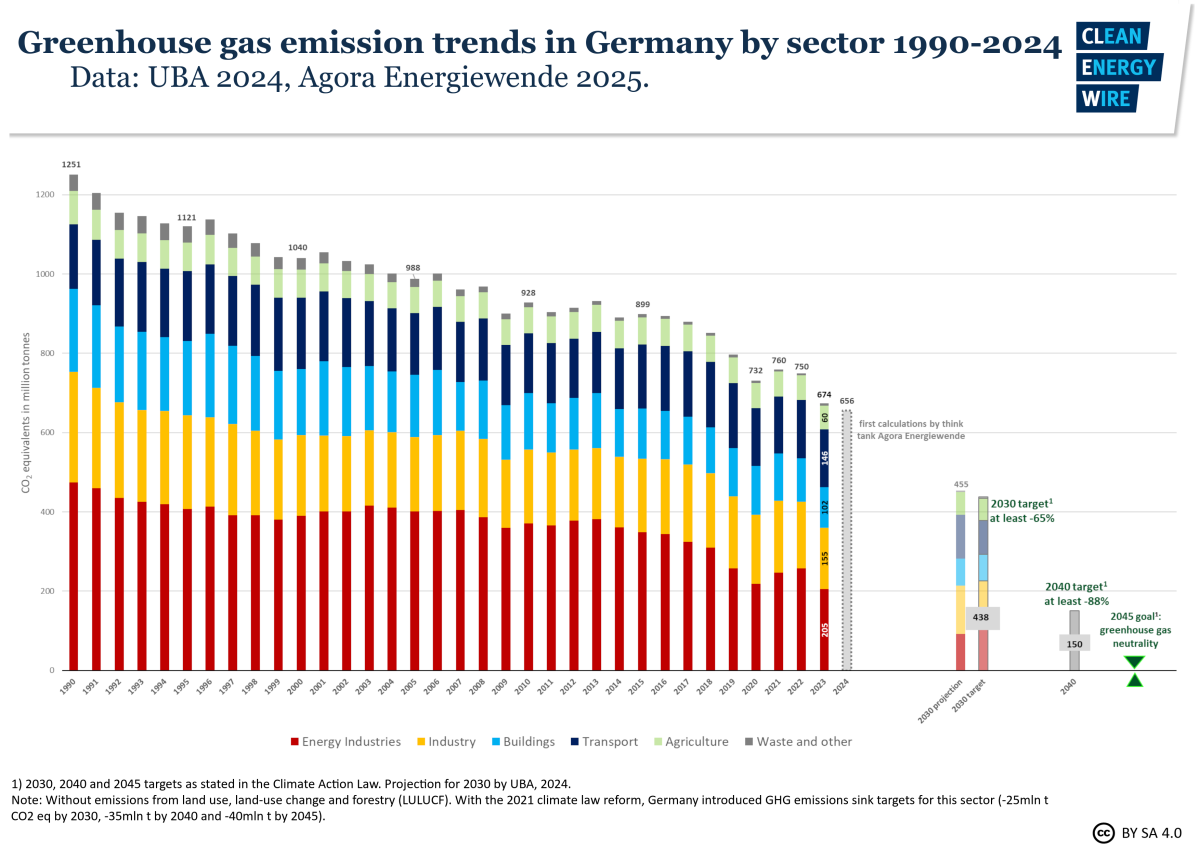

Germany’s national climate targets

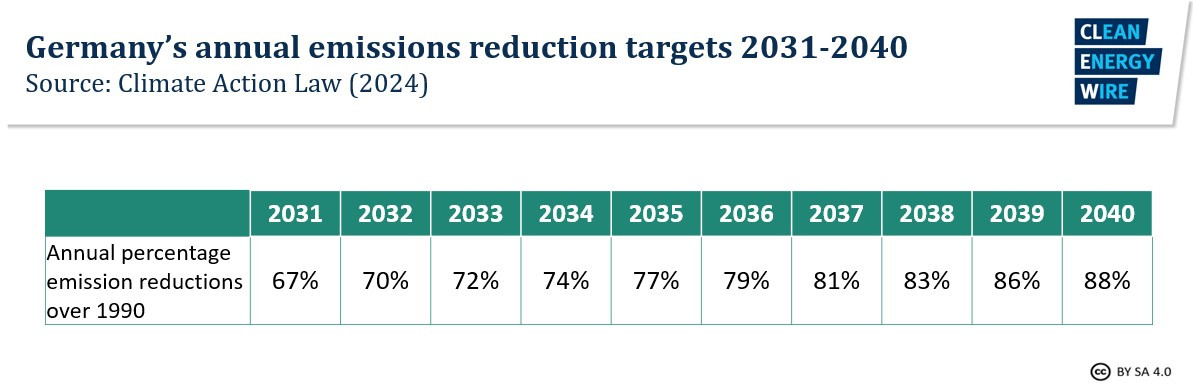

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 65 percent by 2030 (compared to 1990)

- At least 88 percent by 2040

- Net greenhouse gas neutrality by 2045

- Negative greenhouse gas emissions after 2050

- Ambition of national targets can be raised should this be necessary to meet European or international obligations – but not lowered

Contribution of LULUCF

- Increase contribution by the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector:

- At least minus 25 million tonnes CO2 eq by 2030

- At least minus 35 million tonnes CO2 eq by 2040

- At least minus 40 million tonnes CO2 eq by 2045

Technical carbon sinks

- Government sets targets for technical sinks for 2035, 2040, 2045 (has not happened, yet)

Annual emission budgets

- Law defines binding total annual emission budgets for the years until 2040 (by 2032 decision on limits for 2041-2045)

- Long-term budget approach: if a target is missed or overshot, the difference will be subtracted or added to budgets of the following years

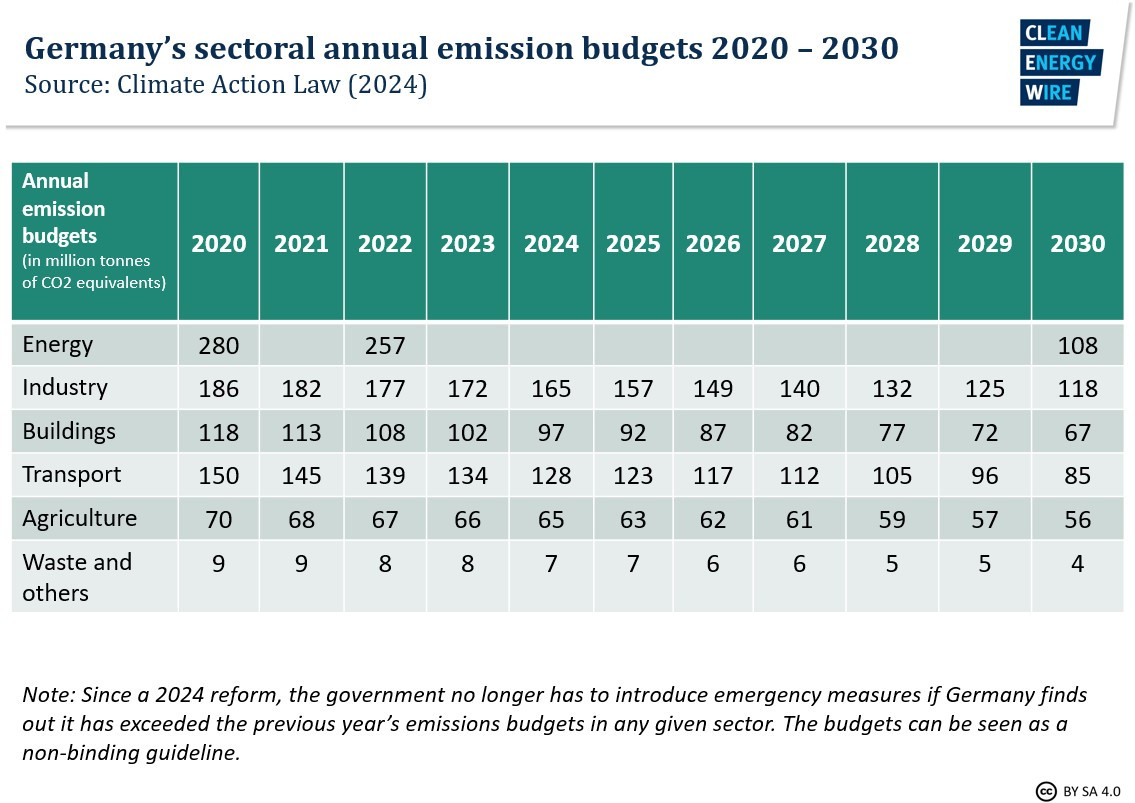

- Law also defines non-binding annual emissions limits by economic sector, to show whether sector is on track (energy, buildings, transport, industry, agriculture, waste and other)

Emissions projections

- German Environment Agency (UBA) annually (mid-March) prepares projections report for future emissions

What happens in case of target miss?

- Since a 2024 reform, the government no longer has to introduce emergency measures if Germany finds out it has exceeded the previous year’s emissions budgets in any given sector. Instead, the focus shifts from past emissions to future emissions, and to a view across sectors:

- The government must present additional measures if, for two consecutive years, the emissions projection reports show that total emissions are set to exceed the sum of the annual emissions budgets until 2030 (later until 2040).

- Responsible ministry must make proposals for measures, full cabinet decides package at latest by end of calendar year

Climate action programmes

- Each new government must present new climate action programme within 12 months from the start of the legislative period, which ensures targets can be reached

Reporting

- Government publishes annual climate action report (with emissions data, status of implementation of climate action measures and effectiveness, status & projections for CO2 pricing within EU every two years)

Independent Council of Experts on Climate Change

- Independent five-person expert council on climate issues will be set up by federal government (experts on climate science, environment, social issues, economy)

- Council presents report on emissions developments and projections (annually, within two months of UBA emissions data presentation in March)

- Assesses greenhouse gas reduction effect of proposed emergency measures

- Gives opinion on changing annual emissions budgets, climate action programmes

- Government or Bundestag can charge the council with writing special reports

- The five members are:

Marc Oliver Bettzüge, professor of economics at the University of Cologne and managing director of the Institute of Energy Economics (EWI)

Thomas Heimer, professor of innovation management and project management at the RheinMain University of Applied Sciences

Hans-Martin Henning (chairman), director of the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems (ISE)

Brigitte Knopf (deputy chairwoman), founder and director of think tank Zukunft KlimaSozial (ZKS), and

Barbara Schlomann, scientific advisor to the executive director at the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (ISI)

Other key parts of the law

Then-environment minister Schulze argued that Germany’s climate action needs to become “more binding, so that we actually implement what we have committed to internationally.” The minister thus aimed to draft the law in such a way “that we can reach our targets in a plannable, reliable and fair manner”.

In addition, the EU climate targets are already legally binding for Germany, and national regulation must reflect this to ensure targets are met.

For sectors included in the European Union's first emissions trading system (EU ETS) – power production, energy-intensive industry and civil aviation – there is a combined EU target to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 62 percent by 2030 (over 2005).

For non-ETS sectors, such as transport, buildings and agriculture, each country was assigned its own target. Germany must reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all non-ETS sectors combined by 50 percent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels.

From 2027, an additional emissions trading system (EU ETS II) will cover fuel distribution for road transport, buildings and additional industrial sectors.