EU push for green finance compels Germany to develop coherent strategy in 2020

Finance as a means for climate action has finally come forth from its niche in Germany and looks set to play a rapidly growing role in climate and energy policy in 2020. Multiple efforts to make the financial sector more sustainable are being made or have already taken effect and a fierce debate seems to be in the offing about how the interests of financial investors and policymakers – profits and price stability – can be married with the broader goal of environmental protection. On top of that, rapdily developing regulation for green finance at the EU level puts external pressure on German policymakers to come up with a coherent position on how it plans to better integrate financial sector in climate policy.

Proponents of green and sustainable finance efforts were able to celebrate several important steps that shifted the financial sector into the limelight of Germany's climate policy in the past year. A government committee in early 2019 set the goal of making the country a leading sustainable finance location. In October last year, government representatives reiterated the ambition and said the country would aspire to forge a "global consensus" for a new financial architecture in international forums like the G20.

Moreover, the climate package launched in September explicitly recognised the role financial policy plays for advancing or undermining climate targets and included concrete measures to make finance an active driver of more sustainable development, for example by issuing green state bonds or aligning public investment funds to sustainability principles.

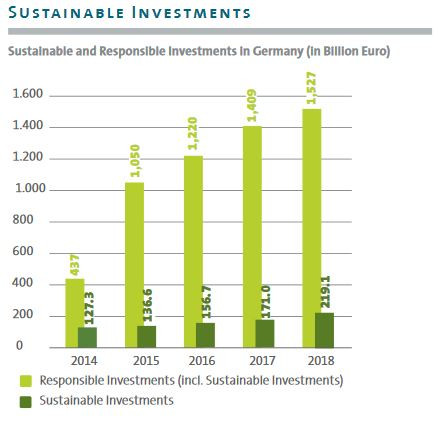

Even though sustainable investments still only account for a small fraction of about three percent of all investment activities in Germany, the volume of assets managed in retail funds under the so-called ESG (environmental, social, governance) criteria in Germany has doubled over the past five years from 15 to over 30 billion euros, according to the German Investment Funds Association (BVI).

Christian Sewing, head of Germany's largest bank Deutsche Bank, said the trend towards sustainable investment does not look to be short-lived. "Over 50 percent of all heirs already ask for sustainable investment options," Sewing said at a conference organised by the newspaper Die Welt in January 2020. Sewing said he believes that a company's sustainability ratings in five- or ten-years’ time would become "just as important as the standard financial credit rating done by Moody's or other rating agencies."

Many major companies in the country, such as industrial heavyweight Siemens or chemicals producer Lanxess, last year announced they would link future credit lines to fulfilment of the ESG criteria, thereby anticipating tightened regulation. Financial control authority BaFin issued a bulletin on sustainability risks and planned regulation in September, saying it expects companies to engage with these issues and to document their efforts "in an appropriate manner." Fund association BVI commented that while it recognised the need for better preparation, the BaFin proposal would ignore difficulties like scarce data on compliance or rules that are too detailed and urged that national regulation should not exceed that in force in Europe.

In order to minimise the disruptive effects of climate change and political responses to it on financial marekts, the Paris Agreement has stipulated a harmonisation of financial flows and emission reduction targets as one of its long-term objectives. This "shifting of the trillions" is meant to happen on two dimensions: First, by ensuring that investments do not run counter to emission reductions and, second, by raising capital for climate action measures. This implies systematically drying up financial flows that clash with reduction targets as well as a set of financial market reforms, such as a mandatory disclosure of climate-related risks, “Paris-compatible” investment criteria, adequate CO2-pricing schemes, stress-tests for credit systems, cutting fossil subsidies and decarbonisation roadmaps for industrial companies.

All of these measures are comprised in the concept of sustainable finance, which aims to ensure that the full impact of investments is understood and resulting risks are weighed against potential profits accordingly. Sustainable finance typically is based on so-called ESG criteria, which gauge the environmental, social and corporate governance dimension of capital flows. From a climate action perspective, the focus naturally rests on investments’ environmental aspects and is commonly referred to under the term “green finance”.

Better integration of the financial sector in climate and environmental policy has become an urgent matter for the EU. The bloc's sustainable finance strategy cleared a major hurdle in December, when the European Council and Parliament agreed on a so-called taxonomy to classify investments according to their degree of ESG compliance. According to the European Commission, the sustainable finance rules will mobilise the trillions of euros in capital needed for the transition towards a carbon-neutral economy, which it has set as a goal for Europe by 2050 in its Green Deal.

Germany has set up a Sustainable Finance Advisory Council (SFC) with members from the financial industry, industrial companies and civil society organisations to devise a strategy that will help the government bring finance in line with sustainable development goals and make the sector fit for forthcoming EU regulation and increase international competition on growing green finance markets. While the council's members still were at odds over key points of their strategy at a first press event in October, such as the degree of obligation for financial companies, there was at least consensus about the need for a strategy.

A first interim report would be released in early 2020, Matthias Kopp, head of sustainable finance at environmental organisation WWF and member of the German government's advisory council, told Clean Energy Wire. Kopp said that Germany had to make up its mind soon and pursue a much more hands-on approach to avoid falling behind in green finance internationally. "It's highly recommended the German government lays out its own idea as to the design of guidelines for regulating financial markets."

Kopp said the taxonomy is "by no means" completed yet and so far, it merely addresses the legislative level regarding how and where it should apply, as well as elements of its scope and mechanics. Important questions, such as whether the classification system agreed on for investments would also apply to lending and thereby impact the core business of banks, have yet to be answered -- a process that might extend well into to 2020s, he said. "Only then will the taxonomy be fully applicable."

In contrast to the position of many financial companies, the environmental activist said Germany should not simply follow EU regulation and instead set an example to other European countries showing it is serious about the financial sector's reconfiguration. Kopp said it could oblige banks to establish transparency for national regulators, such as the control authority BaFin or the central bank (Bundesbank), and apply the taxonomy on the lending side independently of the EU. "Germany needs to find a position on all this and also develop an idea how it is going to work in practice regarding staffing, institutional workflows and so on."

A swift positioning might be advisable given the German government's goal to gain leadership in sustainable finance in the region. Its ambition could be tested by its most important neighbour France, which has already made headway by legally obliging investors to disclose their investments’ carbon footprint and which enters 2020 with a joint project between the government and investor initiative 2° (2DII) meant to align national policy with the new European finance architecture. According to 2DII, the project will root climate scenario analysis, stress testing and climate-related disclosures in line with the Paris Agreement in France's financial sector and help turn the country into a "pilot market" for this budding branch of finance.

Too big to just stand by - Germany's financial sector faces climate challenge

While France bit the bullet following a decision not to include nuclear power in the EU taxonomy's category of "green" investment, another decision by the European Investment Bank (EIB) to ban natural gas investments in the same fashion came as a blow to the German government's energy transition planning. Chancellor Angela Merkel's government considers the fossil gas to be an important bridge technology during the parallel phase-out of coal and nuclear power before it is gradually replaced by "green gas" produced with renewables.

EIB head Werner Hoyer told the newspaper Handelsblatt in an interview that his bank would cut all funding for purely fossil energy projects by 2022 and devote half of its lending to climate protection projects. "This doesn't mean that the other 50 percent will be used to fund projects that destroy the planet," Hoyer said, adding that fossil investments in many cases could also hardly be justified from an economic point of view. However, the EIB head stressed that a functioning taxonomy would have to lie at the heart of all European efforts to turn finance into an asset for the climate. "More transparency and better guidelines are very important – also beyond Europe's borders."

Pressure on Germany to reconsider its financial policy also comes from another EU institution. The new head of the European Central Bank (ECB), Christine Lagarde, said she would seek to utilise the ECB's influence to align monetary policy with climate targets, calling it a “mission-critical” priority for the bank. Lagarde's announcement looks set to put the ECB at odds with German Bundesbank head Jens Weidmann, who made it clear he does not intend to extend the central bankers' range of duty to climate policy. "Our mandate is to maintain price stability," Weidmann said in October.

According to the EU treaties, the ECB's mandate is to support the bloc's general economic policy insofar as this does not impede on its primary aim of keeping inflation stable. The Bundesbank's board acknowledged that systemic risks for the economy will grow while countries continue to rely on fossil power and that policies to curb climate change would become increasingly disruptive the later these are implemented. Banks that have granted loans to companies with a carbon-intensive business model or whose assets are largely fossil-backed are therefore at risk to become implicated in difficulties arising from decarbonisation efforts. However, Weidmann said that pursuing environmental policy goals still could overstrain the ECB's capacities.

Christoph M. Schmidt, head of the German Council of Economic Experts and an early advocate of a national carbon pricing system, also told the Rheinische Post in an interview that the central bank's mandate should remain limited to serving monetary policy. Environmental as well as fiscal policies have to remain the prerogatives of member states, Schmidt said. "The ECB should not attempt to make up for the lack of ambition in climate policy by national governments."