Germany's finance industry struggles to marry climate action and business strategy

Financial companies are often seen as harbingers of new trends and developments that eventually find their way into other sectors of the economy. Their lending and investment choices are usually preceded by meticulous vetting of credit takers and decide which goods and services will enter the market a few years later. They analyse trends in production and consumption and keep a close watch on political debates and technological changes to aid in their decision-making. But when it comes to Germany’s energy transition, the country’s established banks, insurers and asset managers have often fallen short of this pioneering role and instead have found themselves running after trends already well underway.

To be sure, German banks, with their complex network of public, cooperative and purely commercial institutions, have on the one hand been central to funding the country’s Energiewende, the parallel phase-out of nuclear power and fossil fuels and roll-out of a more efficient energy system based on renewables. But rather than being systematic and foresighted, their approach has been piecemeal and often contrary to national and international emissions-reduction efforts, according to an analysis of the German finance sector’s role in the energy transition by the University of Stuttgart.

But growing voter pressure on policymakers to step up climate action in all sectors, alongside bustling international competition, mean Germany’s financial companies can no longer afford to take a back seat on green finance. Regulatory changes are around the corner and business prospects are evolving rapidly. “Banks that neglect sustainability don’t just increase their operational risks. They will also no longer find investors in the long run,” Germany’s finance regulator BaFin warned in early 2019, saying it would require all banks, insurers and asset managers registered in the country to submit “fitness checks” before year-end, assessing how well they can cope with coming changes.

Climate action and other sustainability aspects in investment and lending, often summarised under the ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance) criteria, only saw a considerable push after the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, said Peter Jonach, head of sustainability at the Association of German Banks (BdB), calling the agreement to limit global warming “a watershed moment” for the industry. Indeed, financial companies in Germany since have begun to band together in various networks to streamline their positions on the looming regulatory overhaul.

What was a marginal market segment just a few years ago is now being debated at the top level, according to a survey by industry cluster GSFC on the current state of play of sustainable finance in Germany ahead of anticipated regulatory reforms. “It’s clear that concrete guidelines and goals will be set up that are going to influence the way banks conduct their business,” said Jonach.

Early on, sustainability reporting was often limited to emissions reduction improvements for bank buildings or business trips. But this rather cursory approach now needs comprehensive reform to comply with impending regulatory changes in the European Commission’s sustainable finance initiative. Central lines of action the EU will take to tighten the rules on green finance are establishing a so-called ESG taxonomy, meaning commonly agreed classifications of what constitutes sustainable investments, improving financial climate risk management with agreed benchmarks, and increasing investment transparency through broad disclosure regulations. Since Germany represents about one quarter of the EU’s funds market, the initiative’s overall effectiveness will to a considerable extent depend on proposed measures’ success in Germany.

Apart from compliance requirements, financial companies lacking a clear green finance strategy may miss out on a defining trend of the future economy. About 40 percent of global energy investments by 2025 are projected to flow into renewable power. Likewise, rising demand for energy storage, more energy-efficient buildings and clean-mobility solutions will likely expand green finance markets. Already, energy companies across Germany and Europe are scrambling to decarbonise their assets, and carmakers are revamping their product lines. Indicative of looming changes in one of the most important asset markets, Germany’s real estate association ZIA called for a clarification of green investment credentials so costly refurbishment measures or tighter standards for new buildings do not wipe billions off investor portfolios.

But a more profound restructuring of investment approaches may have begun in Germany. 2019 figures from the Sustainable Investment Forum (FNG), an industry association that analyses sustainable asset management in German-speaking countries, showed that the capital managed under ESG criteria grew by almost one third to 219 billion euros, notably as “substantial market actors” began to systematically incorporate sustainability aspects into their products. However, FNG also found that more than 95 percent of all assets under management do not factor in ESG at all.

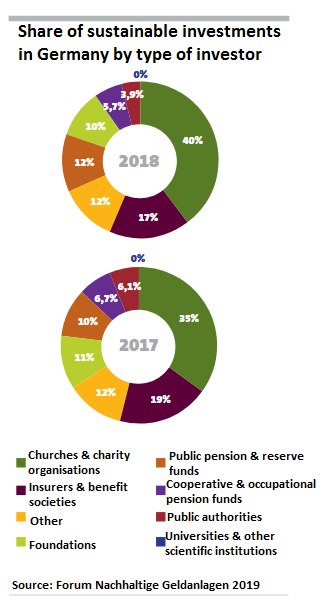

In spite of the surge in activities financial companies still are not at the forefront of their sector's sustainability trend. With a share of 40 percent, the largest group of ESG investors were civil society actors, especially church banks and welfare organisations, FNG said. Insurance companies made up just under 20 percent and banks were relegated to the category “other”, together with unions and other capital holders.

In 2019 NGO Facing Finance analysed the sustainability performance of banks operating in Germany, showing that small and specialised competitors, like GLS from Germany or Triodos from the Netherlands, easily outperformed bigger competitors like Commerzbank and Deutsche Bank. While the average performance of all banks slightly improved and some, like publicly-owned Landesbank LBBW, were able to considerably step up their sustainability performance, larger banks fell short of fulfilling more than half of the NGO’s sustainability criteria. At the same time, Dutch Triodos led the international Clean Energy Pipeline ranking for the highest number of financed renewable power projects for the fourth consecutive year in 2018, outpacing far bigger competitors.

According to consultancy McKinsey, “strong financial partners” for green finance still are few and far between in Germany and indeed Europe, just as public funding schemes for renewable projects are gradually being replaced by more open market mechanisms. The complicated merger and parallel asset swap between German utilities RWE and E.ON is just one example of how a changing energy landscape requires financial actors to accompany such deals, McKinsey said.

A big hindrance to financial companies’ adoption of green principles is the contested definition of sustainability in finance. Existing approaches range from excluding projects with activities harmful to environmental or social goals, searching for best-practice examples in particular industries, to targeted sustainability support based on international standards, such as the UN’s Responsible Banking principles. The complex and multi-level interactions on capital markets give rise to a variety of ESG concepts and hamper agreement on a frame of reference. But regardless of the definition, political choices are immediately reflected on markets. When the German coal exit commission announced its plan to phase out coal over the next two decades, investments that excluded coal quickly shot up, from about 12 billion euros in 2017 to almost 73 billion a year later.

At a 2018 Deutsche Bank-sponsored conference, Gerald Podobnik, head of sustainable finance, said Deutsche was ready for green finance, after it started integrating ESG data into its research in 2018 to accommodate rising worldwide demand for responsible investments. But Podobnik also said the key to “leaving the niche and entering mass markets” lies in harmonised regulation. “We and our entire industry wish for clear rules by the European Commission,” he said.

At the same time, asset managers do not want a political consensus on ESG criteria that could curtail their operational freedom more than they deem necessary. Thomas Richter, CEO of German Investment Funds Association BVI, said existing EU regulation was already tying up "enormous capacities" and worrying its members, of which Deutsche Bank’s asset management branch DSW is one of the largest. Before introducing new rules, the EU should "examine the overall impact of existing rules and either improve or simplify them as necessary," Richter said.

To reduce the impact on their business, companies also want to cash in on the expected transformation. Commercial banking association BdB called for relaxing requirements to make business easier, such as lowering liquidity standards for green products. Since most company investments in Germany are still funded via bank loans rather than equity, such measures are needed to ensure that investment activity supports national emissions reduction, the BdB argued.

Germany’s public banking sector association DSGV, which represents the influential and dense network of regional Sparkassen, warned against measures that could destabilise markets. Regulation should include incentives to offer and buy green finance products, DSGV said in a position paper on the EU’s plans, but it warned against lifting requirements that avoid speculation and drastically influence investor choices. A ‘green supporting’ factor to hasten market entry for sustainable products through laxer control, and a corresponding ‘brown penalising factor’ that pushes out carbon-intensive activities, should only be employed on a broader scale after evaluation of their relative risk performance, they said.

“The financial system’s stability must not be compromised by the planned measures to strengthen its sustainability,” the public banks’ association said, calling for a “lean and flexible” taxonomy that is still capable of detecting “greenwashing”. This is necessary for small and medium sized-enterprises, the backbone of Germany’s economy, to incorporate sustainability aspects, the DSGV said. It also called for compensating the costs of more stringent vetting. “Investor numbers will only significantly rise if there’s a measurable advantage regarding returns,” the association concluded.

Financial companies will likely incur costs from setting up sustainability counselling for their customers. However, performance analyses comparing the returns of sustainable investments with those of conventional financial products suggest that perceived disadvantages of sustainable investments are unfounded. If anything, assets that take environmental and social ramifications into consideration even tend to perform slightly better on average, Deutsche Bank’s research department found already in 2015.

Christian Klein, corporate finance researcher at the University of Kassel, told Clean Energy Wire it used to be “common wisdom” among large investors that sustainability criteria would violate their core aim of maximum returns. “But this logic is now being reversed,” Klein said, arguing that if sustainability offers equal or even better performance, such products should be considered right from the start. “From a capitalist perspective, opting for sustainable investment options should be a no-brainer,” he added.

Financial decisions always carry an element of risk management and risk assessment procedures have come under scrutiny as companies are worried about the ‘carbon bubble’ – the idea that their fossil assets could lose value rapidly. Apart from direct risks, financial actors also see mounting challenges to the reputation of carbon-intensive companies. As experts for financial risk management, the EU’s sustainable finance planning therefore also targets insurers by pushing for better integration of ESG in their analyses through European insurance and asset market regulators.

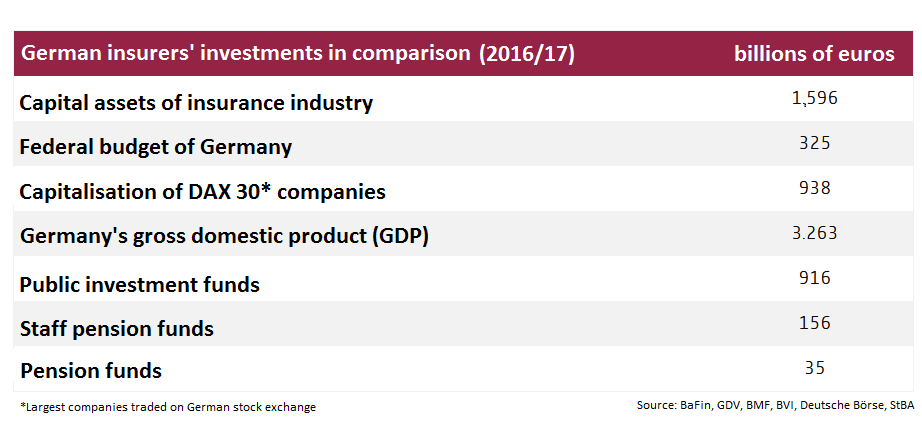

Like banks, insurance companies in Germany are split into public and commercial institutions and together they form the largest institutional investor group. Two of the largest insurance companies in the world, Allianz and Munich Re (the latter being a re-insurer, which insures other insurance companies) also hail from Germany. Global warming poses challenges to insurers on several levels. Apart from direct insurance claims associated with more wildfires, droughts or floods, for which existing risk assessment models are becoming increasingly ineffective due to changing weather patterns, insurers also face pressure to eliminate coverage for emissions-intensive projects that could later entail liability risks from litigation, and to withdraw their considerable assets from fossil fuels.

"As a leading insurer and investor, we know exactly what the devastating consequences could be when climate policy is exhausted in debates, yet no action follows," Allianz CEO Oliver Bäte said in early 2019, signalling that insurers have understood the scale of the challenges ahead. Ernst Rauch, chief climatologist at reinsurer Munich Re warned in an interview with Handelsblatt that the increasingly noticeable effects of global warming clearly come with rising costs for insurance takers. "Despite the odd year of decreasing costs, things will become more expensive."

Already within the next two decades entire market segments, such as housing projects in areas prone to extreme weather events like Florida, could enter a stage of "un-insurability", he said. Rising risks mean rising prices for insurance customers, eventually reaching a point where many homeowners can no longer afford proper insurance coverage at all. "This cannot be in our interest," Rauch said, adding that citizens should speak out on "supporting regulation" for emissions reduction.

In fact, large insurance companies seem to be heeding calls for divestment and withdrawal from the fossil industry. Allianz announced it would make its investments completely climate-neutral by 2050. “We are very serious about this,” CEO Bäte said. Already in 2018, the company announced it would stop selling insurance coverage to coal companies, a move mirrored by reinsurance companies Hannover Re and Munich Re, which took similar decisions to reduce their risk exposure.

While the insurers' climate risk assessment might come across as reliable – both in terms of liabilities and of reputation – when it comes to regulating asset management, their rationale resembles that of banks. Regarding the planned EU taxonomy, the German Insurance Association (GDV) warned against "rigid" policies that could end up regulating insurers too much. A lack of mutual understanding as to what is “sustainable” could boost the potential costs of legislation considerably, GDV warned, arguing that no disclosure or customer advice rules should be introduced before a taxonomy is agreed.

In the meantime, the GDV called for "voluntary expansion" of sustainable finance practices "based on competitive conditions and freedom of implementation method". They said this would lead to a far more efficient integration of ESG principles than any regulation. Insurance companies then could hold customers accountable for presenting sustainability concepts by adjusting underwriting premiums, meaning that higher sustainability risks will result in higher payments to the insurer for providing cover. According to a survey by financial services authority BaFin, Germany's insurance companies seem confident they have solved the problem of defining sustainable finance at least for themselves, saying that over 70 percent of their relevant assets were already managed sustainably. However, the financial controllers noted the results would depend vastly on the companies’ own interpretation.

Asset management - The handling of financial investments by a professional agent

Best-in-class – Investment strategy that opts for funding leaders in given rankings in industries, technologies or categories

Carbon disclosure - Publication of climate-related activities by companies; spearheaded by NGO Carbon Disclosure Project and its disclosure leadership index

Corporate governance - The compliance of a company with laws, guidelines, voluntary agreements and other norms in its business conduct

Divestment – Withdrawal of capital from funds, equity or other capital assets from certain businesses or fields of operation, such as the coal industry

ESG –The Environmental, Social and company Governance dimension of business activities

ESG-Integration – The explicit inclusion of ESG-criteria in traditional risk analysis

Engagement – Long-term dialogue with invested companies to adapt investment decisions to ESG considerations

Exclusion criteria – Systematic elimination of certain investments or other categories, like companies or states, if they fail to abide by certain standard practices

Green Bonds – Bonds issued with the condition to finance environmentally friendly projects

GRI Standards - Globally used standard for sustainability reporting in finance launched by the Global Reporting Initiative Framework (GRI) since 1997

Impact investment – Investments made with the aim to make financial gains while also deliberately influencing ecologic and social developments

Integrated reporting - The inclusion of environmental and social impact information in company reporting to indicate financial and non-financial business aspects in parallel

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) - Screening of funds to exclude companies which generate a given share of their revenue with activities conflicting with given environmental, social or ethical values

Sustainability-themed funds – Financing of business areas or other assets that are associated with sustainability and have a connection to ESG-criteria

Norms-based screening – Evaluation of investments according to given international standards, such as the UN Global Compact, OECD guidelines or others