Taming the appetite for energy

Experts

- AGEB - AG Energiebilanzen e.V.

- Agora Energiewende

- BMU - Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (until 2025)

- BMWi - Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (until 2021)

- BUND - Friends of the Earth Germany

- DENEFF - German Industry Initiative for Energy Efficiency

Content

Too good to be true?

Less is more

Lagging behind targets

Earning money with efficiency

Can efficiency ever become “sexy”?

Too poor to save

Investors vs Users

Carrots or Sticks?

Too good to be true?

Efficiency offers so many benefits it almost sounds too good to be true. Who could find fault with the main idea behind it: Getting more out of the energy consumed? The advantages of cutting waste and pursuing efficiency are so numerous it sounds like a no-brainer – and experts consider it essential to the success of Germany’s energy transition.

“Efficiency is absolutely indispensable to make the Energiewende a success. It is our most important energy resource,” explains Christian Noll, managing director of the German Industry Initiative for Energy Efficiency (DENEFF). Efficiency specialist Robert Pörschmann, from Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND), agrees: “Germany can achieve its emission targets much faster if energy is used more efficiently. This buys time, which is in very short supply in the fight against climate change.” Matthias Zelinger from the German Engineering Association (VDMA) says rising energy prices make efficiency a strategic factor for German industry. "Companies can gain cost advantages, and efficiency becomes a competitive advantage."

But at the same time, experts lament that progress in the area is disappointingly slow. “Efforts have got stuck. We’re lagging behind in all areas,” Noll told the Clean Energy Wire. So what is so difficult about saving energy?

Less is more

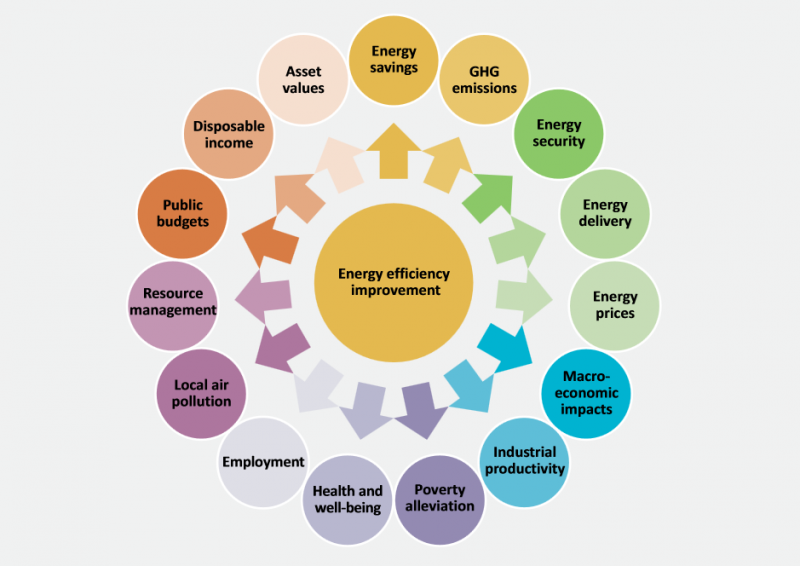

The government gave efficiency a big push last year by publishing the National Action Plan on Energy Efficiency (NAPE). It declares energy saving the ”twin pillar of the energy transition” - on a par with the roll-out of renewable energies, which has been basking in the limelight by comparison. The document argues that saving energy is so crucial because it contributes to all three main aims of German energy policy at once, making it: firstly, environmentally friendly; secondly, secure; and thirdly, affordable.

-

Efficiency and the environment: Indeed, saving energy is a fundamental and, most experts would add, neglected part of Germany’s plans to cut CO2 emissions. By 2020, the country wants to cut total energy consumption by 20 percent compared to 2008. By 2050, the target is to get by with only half the amount of energy, so CO2 emissions can fall by at least 80 percent compared to 1990 levels (for more details, see Factsheet on Germany’s climate targets). This is unchartered territory as no advanced economy has ever tried to reduce energy consumption to this extent. BUND’s Pörschmann also points out that a significant cut in energy consumption means fewer windmills and transmission lines, which often meet local resistance, need to be built. “Efficiency can drastically reduce the need for interventions in natural habitats,” he says. This also saves costs and land.

-

Efficiency and supply security: Efficiency is also seen as key to achieving a secure energy supply. Germany produces only a fraction of the energy it consumes, despite all the buzz about the rise of renewables. The country imports virtually all the oil it consumes, as well as around 90 percent of hard coal and gas, with Russia being the dominant supplier. The Ukraine crisis has brought this relationship into sharp focus. “While energy trading is generally a desirable thing, energy imports also create dependencies. One way to reduce these is higher energy efficiency,” states the NAPE. Stefan Thomas, from the Wuppertal Institute, told the Clean Energy Wire: “Efficiency is immensely important, because it is the biggest, fastest and most economical contribution to climate protection and to supply security.”

-

Efficiency and affordability: Efficiency is key to making the Energiewende affordable, the government believes. Many experts would agree. “Countless studies have shown: A significant increase in efficiency makes the energy transition cheaper for everyone,” says Patrick Graichen, head of think-tank Agora Energiewende. Graichen argues this is crucial to maintain public acceptance of the project, as rising electricity prices tend to dominate the debate about the Energiewende. In theory, efficiency can bring relief for poor households burdened by high power bills. It can also benefit companies by keeping them competitive in the global marketplace.

Lagging behind targets

So where does Germany stand in terms of efficiency? “Germany has undertaken big efforts, but the challenges are immense. We need to cut primary energy use by 50 percent within 35 years,” says Wolfgang Eichhammer, from think-tank Fraunhofer ISI. “There is no lack of willingness to do it and a fair amount of efforts. But we must speed up the process urgently.” Thomas stresses that no other country has ever taken on a comparable challenge. “But with present policies, we can only save a quarter of energy, not half,” he says.

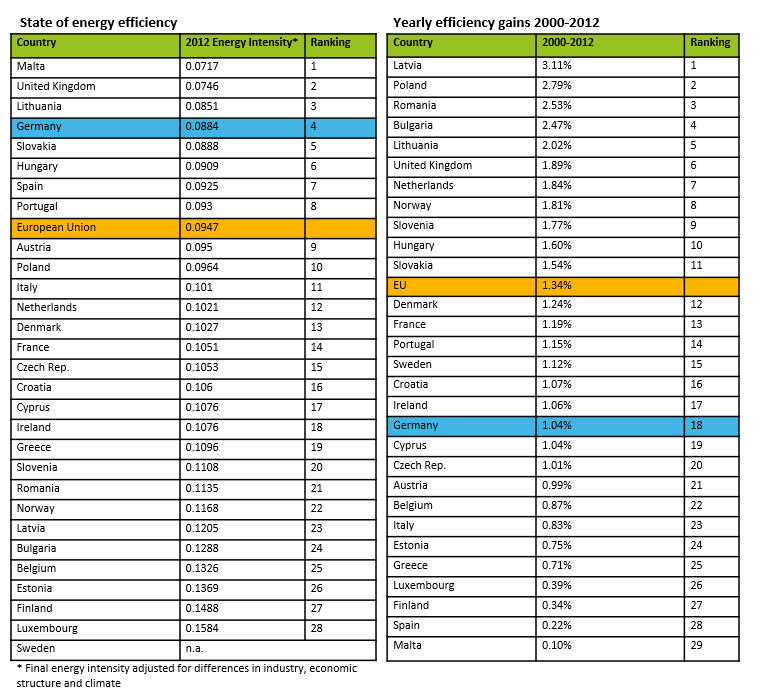

International comparisons reveal that efficiency standards in Germany are relatively high, but recent progress is slow. The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy ACEEE crowned Germany a “world champion” in efficiency in a 2014 study. But an analysis by the German Industry Initiative for Energy Efficiency (DENEFF) and Fraunhofer ISI concluded: “The level of energy efficiency and efficiency policy is good, but many European countries have overtaken Germany in the past 15 years when it comes to progress in efficiency.”

In 2013, the University of Stuttgart concluded a meta-analysis of more than 250 publications on efficiency as follows: “With current efforts and today’s regulatory framework, the government’s targets will clearly be missed.” The EU even started an infringement procedure in 2014 because Germany was too slow to comply with the EU Energy Efficiency Directive.

One reason for slow progress on efficiency is neglect by the previous government, which was in power until 2013. Germany adopted its central climate and efficiency targets in 2010. But the economics ministry was led by Philipp Rösler from pro-business party FDP during that time, and one of the officials in charge even publicly ridiculed the idea of efficiency, saying it reminded him of socialist planning in the former GDR. “Nothing happened on efficiency. You could have even called it a policy of efficiency prevention,” says Pörschmann.

The new “Grand Coalition” government of social democrats (SPD) and conservatives (CDU) gave the subject new prominence with the publication of the NAPE in December 2014. Most experts, from both the business community and environmental NGOs, applauded the publication of the policy document, which put a lot of emphasis on creating the right conditions so efficiency can become a business opportunity and thrive without the need for financial support.

Earning money with efficiency

Volker Breisig, from consultancy PWC, said the NAPE was a turning point for energy efficiency and the companies involved. “Last year, the sombre mood in the industry left us a bit perplexed, but now we can clearly see tender shoots,” he said. The German Industry Initiative for Energy Efficiency (DENEFF) estimates companies specialising in efficiency employed around 850,000 people in 2013, while sales totalled 162 billion euros. DENEFF also sees healthy growth in the sector, with sales increasing around eight percent year-on-year. Zelinger says a recent survey by his engineering association revealed an enormous potential for efficiency investments. "Almost 80 percent of companies specialising in efficiency and energy generation expect their clients to increase investments in efficient technologies."

According to management consultancy PWC, efficiency is a huge business opportunity, creating many jobs in future-proof businesses. The Fraunhofer ISI's Eichhammer is convinced efficiency also offers great export potential for German companies. “Germany is in a good position. Just this morning, I had a visit from a delegation from China’s National Development and Reform Commission, who wanted to find out more about efficiency,” he said. “The subject is gaining traction in many countries.”

There are plenty of business opportunities in the field of efficiency because many investments yield double-digit returns, while interest rates are at historic lows. Experts at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) even argue that efficiency investments can be an important stimulus for economic growth.

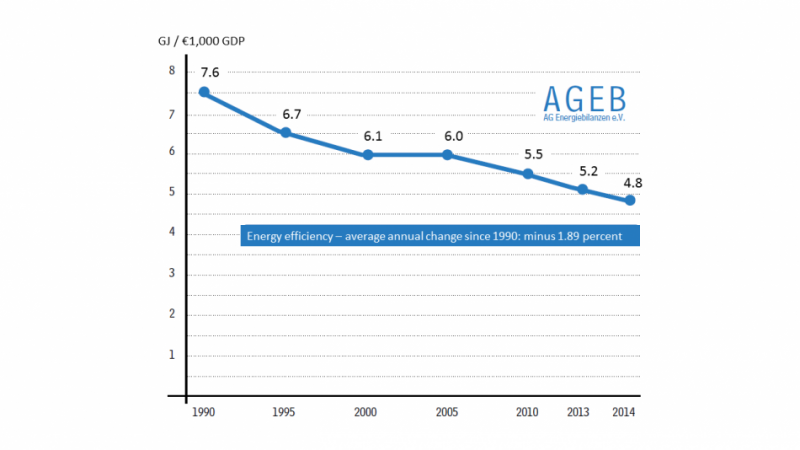

Optimists also point to encouraging signs that efficiency efforts are finally showing up in macroeconomic statistics. According to energy market research group AG Energiebilanzen (AGEB), German households and industry made great strides last year to use energy more efficiently. Just 4.8 gigajoules of energy were needed to produce goods worth 1,000 euros, in 2014. This is a drop from 5.2 gigajoules needed in 2013 and 7.6 gigajoules in 1990, according to an AGEB press release. The group said the results were ‘excellent’ compared to other countries.

“This means Germany has increased efficiency by more than a third within the last 24 years,” said Hans-Joachim Ziesing, a member of AGEB’s managing board. Energy efficiency increased on average by 1.9 percent per year since 1990. Private households increased efficiency by almost six percent last year, while industry used 3.3 percent less energy to produce goods worth 1,000 euros, according to the AGEB results.

But most experts still complain the government is slow to turn the National Action Plan into reality. Many say the issue was dealt a massive setback when planned tax incentives for the insulation of buildings were blocked by Bavaria in early 2015.

The EU also believes Germany is not keeping pace on efficiency: The European Commission gave Germany a final warning in June regarding the transposition of the Energy Efficiency Directive.

Can efficiency ever become “sexy”?

Given the numerous benefits of efficiency, how is it possible that progress on the issue is so slow? The reasons given for this paradox are at least as numerous as the benefits of saving energy, and they range from psychological hurdles to financing problems and technical issues.

The most often heard complaint – be it at conferences or in discussions with individuals - is that “efficiency is simply not a sexy topic”.

“It’s a well-known saying that efficiency is not as ‘sexy’ as renewable energies,” reports the Wuppertal Institute’s Thomas. Fraunhofer ISI’S Eichhammer told the Clean Energy Wire: “If efficiency could get as much attention as wind and solar energy, we would be miles ahead.”

The German parliament’s “Working Group Efficiency” was so frustrated with public perceptions they invited journalists to quiz them about possibilities to “sex up” efficiency in the eyes of constituents. The lawmakers were told many people were simply not interested because they thought the subject was too complicated, too multi-faceted and too diffuse. Journalists agreed efficiency was a hard sell, even in the newsroom, because few readers get passionate about building insulations and new heating systems hidden away in dark cellars – which are also a bad location for photo opportunities.

In the eyes of most people, efficiency also has little to offer in terms of social prestige – who wants to boast about a new heating pump? “Efficiency is hidden in hundreds of appliances, machines, components, so it’s difficult to get an overview. Very often, it is even invisible, so no-one can boast with it,” says Thomas. Many people also associate efficiency with restraint and abstinence, which does not fit well into the dominant consumer culture.

Too poor to save

A central hurdle for many efficiency efforts is the associated cost. In most cases, efficiency gains require an initial investment.

This is why many poor households simply can’t afford to save energy. A more efficient washing machine or LED bulb, both of which would cut electricity bills, are often out of reach financially.

To help people realise how much energy they can save, the German government offers a service in association with the Federation of German Consumer Organisations (VZBV). Thanks to public subsidies, consumers can book a session with an energy specialist at their home to look at ways to increase efficiency in power and heat consumption. But an advisor in Berlin, who did not want to be named, said even the nominal fee of ten euros puts poorer people off - despite average annual saving options identified in one session reaching hundreds of euros. “Most people who book this service are academics who are very energy conscious anyway,” reported the advisor. Another problem is that most people vastly underestimated the significance of the topic for their wallets. Many know exactly how much petrol their car needs but few can name their home’s energy consumption.

The initial investment is also a large hurdle in industry, where efficiency progress is particularly slow. “Final energy productivity is meant to increase 2.1 percent per year. But over the last five years, it only increased by 0.2 percent. So, basically, efforts need to be increased ten-fold,” Noll told the Clean Energy Wire. “Companies just don’t consider efficiency as part of their core business, and they demand unrealistic returns on investment.” The VDMA's Zelinger says many companies will only spend money on efficiency measures if the investment pays for itself within two or three years. "This often translates into the exclusion of economically viably investments, which would yield high returns in terms of their life cycle."

A simple lack of knowledge is also often a factor in the slow progress of efficiency in industry. The government hopes to overcome this with the establishment of industry efficiency networks, where industry representatives can exchange ideas and experiences. “These are very important to overcome non-economic hurdles to investments,” explains Eichhammer.

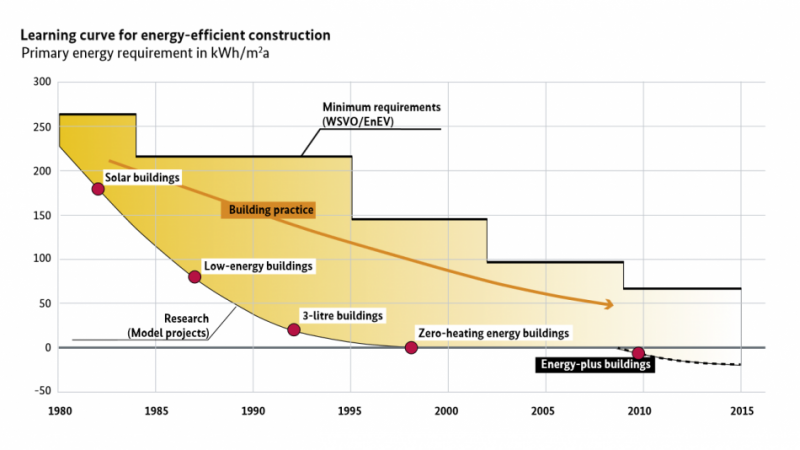

Investors vs Users

In the area of building insulation, the official aim is to renovate around two percent of buildings per year. But progress is far too slow. “The renovation rate is now probably below one percent,” says Noll. Almost 40 percent of total final energy in Germany is consumed in buildings, the largest part of which is used for heating. More extensive building insulations could, in theory, also relieve consumers burdened with high energy costs. But because most Germans are tenants, efforts in this area are hampered by the so-called investor/user dilemma: Tenants are not prepared to shoulder the costs of renovations because they do not know for how long they will stay in a flat or house. Landlords, on the other hand, don’t reap the benefits of lower energy bills. “The rate of renovations must increase rapidly and the issue of financing is crucial,” says Eichhammer. At the Wuppertal Institute, Thomas believes the state has to double financial support to get insulation rates up to speed. Experts at think tank DIW believe it would require an additional annual investment in energy upgrades of ten to 12 billion euros to achieve an annual refurbishment rate of around two percent of buildings, which is necessary to achieve efficiency targets. Efficiency also gets neglected during the construction of new homes because many future homeowners look only at building costs, rather than long-term maintenance costs.

The issue of financing is considered a central obstacle for efficiency investments in both housing and industry. Insecurity about future energy prices and how much energy can be saved creates insecurity about amortisation times, which is why many experts believe new financing models are required to kick-start the process.

Efficiency is also making little headway in transport. One reason is that this area has been neglected by politics, according to Thomas. “Also, progress in engine efficiency has been counterbalanced by a trend to larger cars,” he adds. “Transport is a hard nut to crack for politics, because it is in the interests of Germany’s car manufacturers to sell large cars, which are also status symbols for their customers.”

Carrots or Sticks?

These problems are the reason why many proponents of efficiency make the case for binding efficiency targets, a stringent efficiency law, and new financing models to force the hand of investors. They point to the rapid rise of renewable energies due to the system of feed-in tariffs, which guarantee a steady income stream for 20 years. New building efficiency standards are a further example often cited to show that binding targets might be more effective than voluntary incentives.

“It would be a huge progress to introduce binding targets, just like France and Denmark,” argues Noll. Pörschmann agrees: “Firstly, efficiency targets are not anchored in law. Secondly, the efficiency budget is too small and not secured permanently. Thirdly, we lack an independent coordinating body which can ensure all efforts point in the right direction.”

The government, however, is reluctant to introduce obligatory targets. “A culture of energy efficiency cannot be prescribed by legislative authorities,” said energy minister Sigmar Gabriel (in FAZ).

Critics also insist the government must add an “efficiency first” organising principle for major investment decisions. Many infrastructure projects, such as electricity grids, are planned without ever raising the question of whether the project could become superfluous by investing the same amount of money in efficiency measures. Whenever there is a shortfall in energy provision, policymakers immediately believe generation must be increased, instead of looking for saving potentials.