The road to a new coalition government in Germany

- When do Germans vote?

- Who leads the government after an election?

- What is the process and timeline of finding a new coalition government?

3.1. Parties discuss internally

3.2. Exploratory talks

3.3. Coalition negotiations

3.4. Coalition agreement

3.5. Election of a chancellor - What happens if negotiations fail?

When do Germans vote?

German basic law dictates that voters should head to the polls every four years for the federal parliament elections. Federal elections usually happen in autumn and the next one was originally set for September 2025.

However, the break-up of chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition government on 6 November 2024 heralds in snap elections on 23 February 2025.

Germany has strict requirements for snap elections to guarantee stability for the country. The German Bundestag (federal parliament) does not have the right to dissolve itself, but it can unseat a chancellor by voting in a new one with a majority of its members. The legislative period would then continue until the next regular election. As there was no majority on the horizon for a different chancellor, this option was not possible in 2024.

An early end to the legislative period is tied to the chancellor’s majority in parliament and the federal president ultimately gets to decide. A chancellor can initiate a vote of confidence in the Bundestag and lose, then ask the president to dissolve parliament and call a new election. Scholz lost the vote of confidence in December 2024.

After lawmakers vote, the president has 21 days to dissolve parliament. While he does not have to comply, current president Frank-Walter Steinmeier did dissolve parliament on 27 December.

Once the president decides to dissolve parliament, elections have to take place within 60 days. Steinmeier announced 23 February 2025 as voting day, following an earlier agreement by lawmakers from the government and opposition.

Under different circumstances, early elections could also take place if parliament fails to provide an absolute majority to a chancellor candidate after a parliamentary election. In that case, a chancellor could still be voted into office with a simple majority. However, the president could refuse to appoint that person and call for a new election instead. Throughout German history, all chancellors have reached an absolute majority in the first election round.

For now, Scholz of the Social Democrats (SPD) remains chancellor and ministers from his party and the Greens continue in their positions. However, the two parties’ lawmakers do not have a majority in parliament, which makes agreeing new legislation -- such as the budget for 2025 -- next to impossible, especially because the opposition has little interest in cooperating ahead of the next election.

In Germany's parliamentary democracy, voters do not choose the chancellor directly, with MPs instead electing a candidate. A political faction has seldom reached the absolute majority needed to form a government by itself, so entering into alliances with other parties has usually been necessary.

Germany’s party landscape has been regarded as one of the most stable in the world over the past several decades. It was dominated by two large factions: the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) – including its Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU) – and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) on the other side.

The dominance of the two major factions in German politics declined significantly in recent years. In 2021, both the CDU/CSU and SPD ended up with less than 30 percent of the vote. As the party landscape becomes more fragmented, coalition governments consisting of three or more parties are increasingly necessary to reach a majority in parliament.

In 2017, talks for a three-party government failed. However, in 2021, the SPD, Green Party and the FDP joined forces as the “traffic light” coalition. Difficulty in aligning the parties’ contrasting positions has led to a tumultuous period of governance.

The party with the most parliamentary seats in a federal coalition government usually gets to name the chancellor and is considered the senior coalition partner, tasked with building the alliance. The smaller party or parties are the junior partners. There are no official rules for coalition talks, but certain procedures have emerged over the past decades.

More often than not, parties have to compromise on their election programme pledges. The chemistry between the party leaders, and their bargaining powers, also play a role in how things play out.

What is the process and timeline of finding a new coalition government?

The process of finding a new government alliance in Germany runs parallel to the transition from the old Bundestag to the new one. The federal parliament’s opening session has to take place at the latest 30 days after the election, so by 24 March 2025.

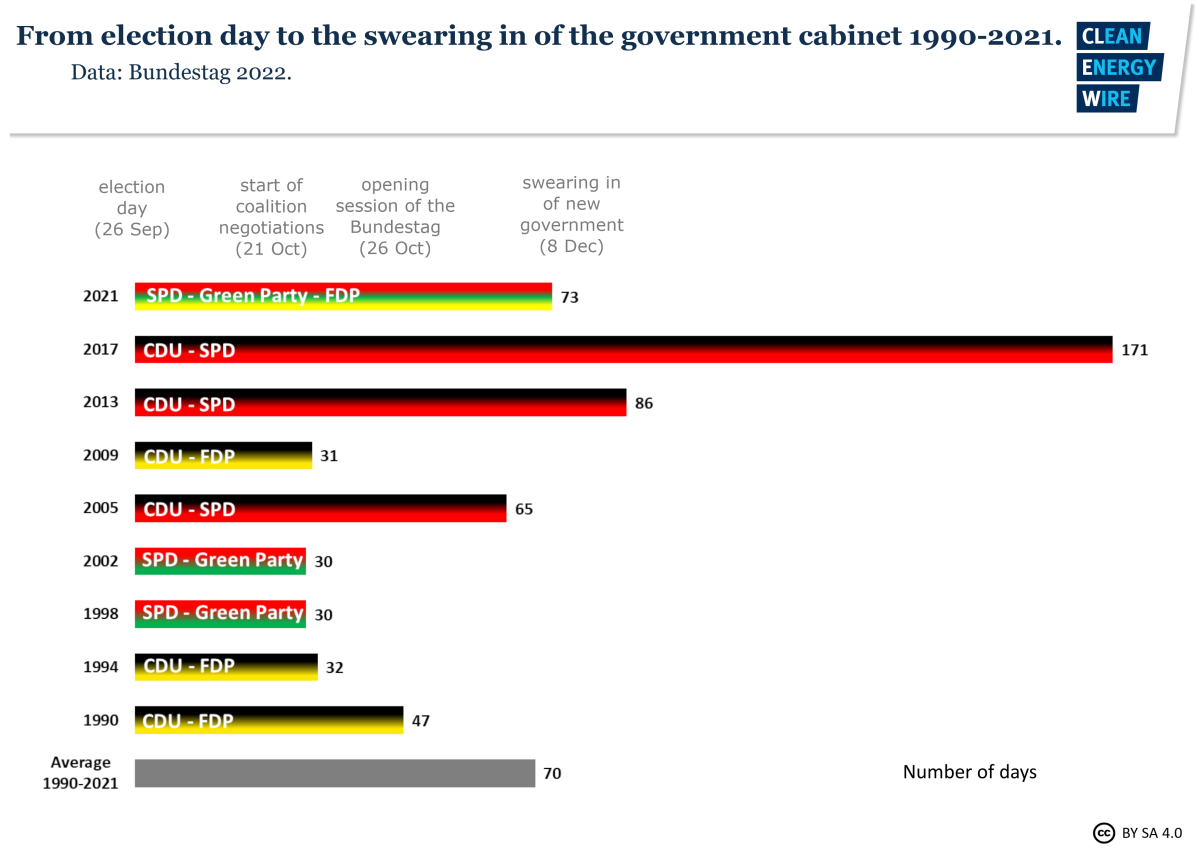

The outgoing chancellor’s term ends with the inaugural meeting of the Bundestag, but the government will be asked by the German president to continue to carry out official duties until a new administration is sworn in. In 2021, a new government was sworn in two and a half months after the election; in 2017, half a year passed before the new government took office.

That means Germany is unlikely to have a new government before late spring 2025.

1. Internal party debates take place in the first week after the election

Starting on the day of the election, each party analyses the outcome and discusses possible consequences. Discussions take place overnight and in party leadership meetings the morning after the election, when preliminary results give more certainty over the potential options for forming a government.

Parties also debate other questions, such as the future parliamentary group leadership, and the group schedule until the new Bundestag members convene for the opening session.

In the days following the election, the parliamentary groups of most parties will meet for the first time and elect their leader.

Before official coalition negotiations begin, party leaders hold exploratory talks (‘Sondierungsgespräche’) to sound out whether forming an alliance is feasible and under which conditions negotiations would take place. Traditionally, the party with the most seats approaches possible partners.

If forming a traditional party alliance is possible, for example between the conservatives and the FDP, these talks are painless. After the 2017 election, however, German politics entered largely uncharted waters, as Greens, economic liberals and conservatives sought to find common ground. Exploratory talks lasted several weeks before the FDP pulled out.

In 2021, both the Green Party and the pro-business FDP were considered the "kingmakers" of a new coalition government. The two smaller parties entered pre-exploratory coalition talks among themselves to figure out potential stumbling blocks and areas of common ground, before entering talks with one of the leading parties. This ended up being the SPD.

Beyond negotiating, exploratory talks also fulfil the important function of starting to build mutual trust after a tough and conflict-ridden election campaign.

If several rounds of exploratory talks are successful, the parties will agree on a format for official negotiations and might present a preliminary policy framework. The 2021 exploratory talks resulted in a document with initial general agreements, based on which the formal coalition negotiations took place.

In the end, all relevant party bodies must agree to formal coalition negotiations. Traditionally, that means the federal leadership, but parties could also decide to ask delegates at a special conference or even let members vote.

Official negotiations between the parties aiming to form a government have taken from two to more than seven weeks in the past. Participation is not limited to newly elected national MPs, but includes other party members like state politicians, outgoing ministers and members of the European Parliament.

When the SPD, Greens and FDP negotiated the terms for the coalition government in 2021, more than 200 politicians took part in the different working group meetings. Almost 30 politicians formed the core negotiating team, including the party leadership, the heads of the parliamentary groups and the general secretaries.

Details of the agreement were developed in 22 working groups, which included climate, energy, transformation; construction and housing; Europe; and mobility.

Discussions initially focus on policy questions relevant to the working groups, but the negotiations are also important for determining the party leadership and how ministries will be set up while in government.. Each party is left to suggest their individual candidates to lead the ministries.

Any final points of contention are debated by the core negotiating team.

A coalition agreement is presented once negotiations have concluded, which includes general policy messages, concrete policy proposals with specific timelines and a breakdown of how ministries will be managed. The agreement is not legally binding and there are no sanctions for breaking it.

The final hurdle for building a coalition is having the agreed-upon policy agenda passed by each individual party. Some – such as the grassroots-oriented Green Party, or the SPD in 2018 – let its members vote on the final deal. Others leave the decision to the party leadership.

When all parties agree, the coalition agreement is officially signed.

Germany would not be left without a government if negotiations failed. The current administration would continue to carry out official duties until a new cabinet was sworn in.

Should efforts to form a coalition fail during the exploratory talks, negotiations, or when attempting to secure party approval, parties elected to the German Bundestag can try to find a different alliance to form a government.

When the FDP pulled out of exploratory talks with the conservatives and the Greens in 2017, the president at the time, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, led talks with all parties present in the new parliament to sound out options for forming a new government. Steinmeier said all of the parties must be ready to compromise, making it clear he wanted to avoid another election. After a meeting between Steinmeier and Martin Shulz, leader of the SPD, the SPD became more open to discussions, reversing their categorical refusal to cooperate with the conservatives. The conservatives and SPD later renewed their grand coalition government.

If no alternative for a majority government can be found, the German Basic Law offers two possibilities. The German president can either name a chancellor who has less than 50 percent of votes in the Bundestag or dissolve parliament and hold another election to try and break the deadlock.