Climate in the 2024 EU elections and the making of the union’s next leadership

Note: This factsheet is part of CLEW's 2024 EU elections package: Climate and energy high on the agenda in run up to 2024 EU parliament elections.

- Why does it matter?

- Who defines the next EU political agenda?

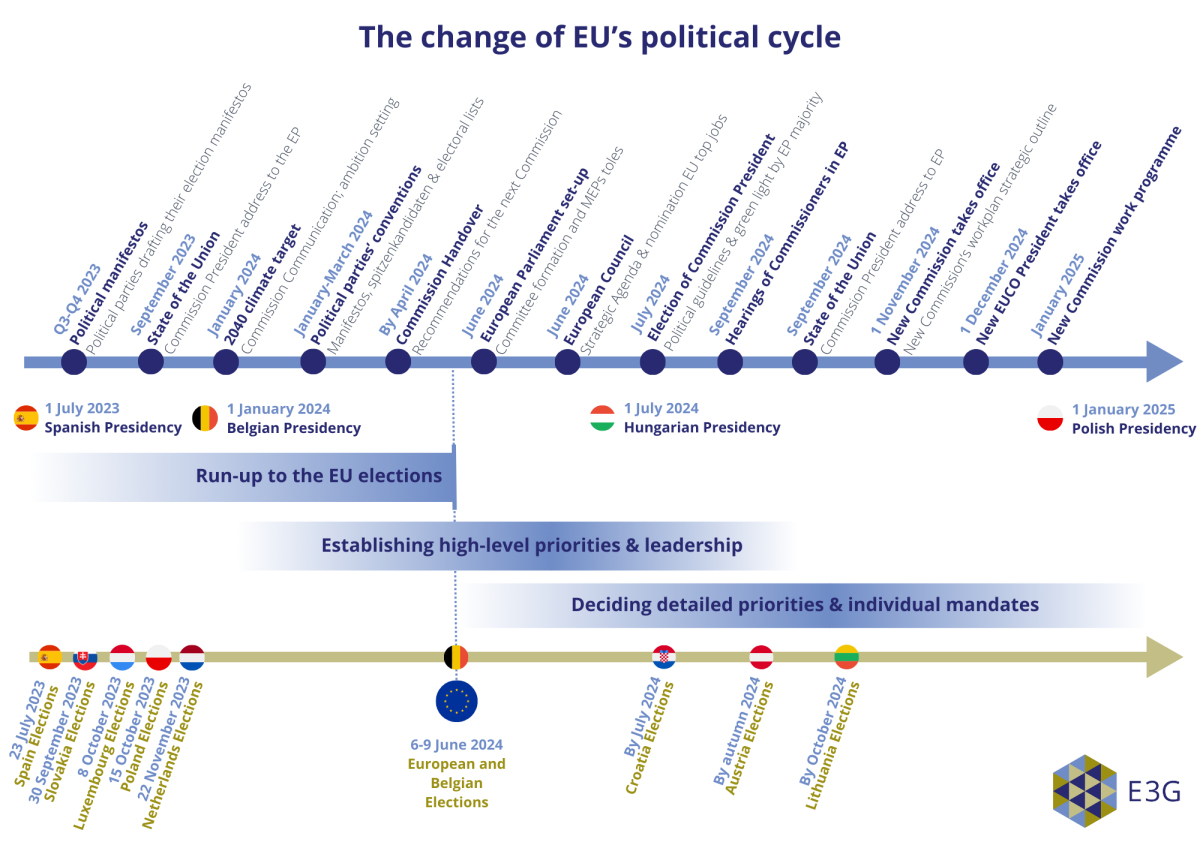

- Key moments – the change of the EU’s political cycle

- The role of energy and climate policy in the EU elections

- Expert contacts and resources

This year marks a period of change for EU policymakers. European Parliament elections in June mean that legislative work is set to wind down in the first months of the year as politicians across the union shift into campaign mode. On 6-9 June, about 360 million EU citizens eligible to vote across the union (21 million first-time voters) can cast their ballot to decide the make-up of the next European Parliament.

Once election results are out, establishing the new parliament in early summer is only the start of a much broader change: the making of the EU’s new leadership. Parliament will elect a new Commission president and confirm her or his team of Commissioners through a series of potentially tough hearings. It could take until late in the year for it to become clear just how ambitious EU climate policy will be in the remainder of this crucial decade for global climate action.

The balance of power in the parliament is set to shift, which could change the institution’s ambitions on climate going forward, and the new European Commission will lay out its policy proposals for the 2024-29 cycle. These are decisive years not only for global climate action – with scientists saying that limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by 43 percent by 2030 – but also for reaching the union’s 2030 energy and climate targets.

In the 2019 elections, Green parties – amid a surge in public concern over the climate and under pressure from the striking youth activists of Fridays for Future - made significant gains in many EU countries in what some commentators called “the first climate election.” The outcome forced the then-new Commission president Ursula von der Leyen to present an ambitious programme on climate to secure the approval of the European Parliament.

With its Green Deal strategy to make Europe climate neutral by 2050, the EU executive set out in 2019 to cement the climate leadership role of the union. The past four years were marked by a comprehensive overhaul of EU climate and energy legislation. While the transition to clean energy looks to be unstoppable, it remains to be seen how high the issue will be on the next Commission’s agenda. The incoming EU leadership will oversee the further implementation and development of Green Deal policies, while also reacting to and dealing with geopolitical crises and their impacts on energy and climate policy.

Current polls suggest a significant shift to the right in many countries in the June vote, with populist radical right parties gaining votes and seats across the EU, and centre-left and green parties losing votes and seats, said the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) in an analysis in late January 2024. In the European Parliament, a populist right coalition could emerge with a majority for the first time, which would likely oppose ambitious EU action to tackle climate change, said ECFR.

The intricacies of EU decision-making and legislation, or the question of who is actually in charge in Europe, have puzzled international partners for decades. The policy priorities for the coming five years are not decided unilaterally – for example by the next Commission president. Instead, there are multiple players and factors which drive and shape the decision-making process and its outcomes.

“The EU agenda for the next political cycle is not a straightforward decision, but rather the final product of several processes starting well before the actual election day,” says Pepe Escrig, researcher at think tank E3G.

The European political parties create their manifestos by early 2024. EU members’ heads of state and governments will agree a “Strategic Agenda for the EU” (likely in June) with priorities for the coming years; and eventually the new Commission president will create their own agenda for the legislative period, informed by this entire process. Once the team of Commissioners is appointed, the new president will send mission letters to each with a mandate and more detailed priorities.

At each stage of the process, interest groups are of course trying to influence policymakers.

EPRS." />

EPRS." />EU citizens will elect the European Parliament from 6-9 June 2024, but there are many other important moments that journalists should keep an eye on, both before and after voters head to the polls.

Unfinished business

There are currently several legislative files on energy and climate where the plenary has not yet made a final decision. These will be deemed to have lapsed by default at the end of the legislature. The new parliament has the option to resume work on individual files, but shifting majorities mean that there is an interest to get as much done as possible by the last plenary session from 22 to 25 April 2024.

Unfinished business includes the final adoption of the controversial Nature Restoration Law, the regulation to reduce methane emissions, or CO2 emission standards for heavy-duty vehicles. A final deal between member state governments in the Council and the Parliament on the three files has already been reached, so – in theory – a plenary vote should just be the rubber stamp.

On other files - such as carbon removal certification - a deal has not yet been reached. Other legislation is in earlier stages of the process, such as the Green Claims Directive where Parliament has yet to agree a position before negotiations with the Council can start.

Every five years, voters across the EU elect more than 700 members of the European Parliament (720 in the election 2024). It is up to each member state to decide the specific rules for how its share of members is elected. In 2024, Belgium is set to be one of five countries where voting is compulsory. The minimum age of candidates in Germany is 18, in Romania 23 and in Poland 21, and the electoral threshold ranges from none to 5 percent. There are, however, some common provisions: Elections take place during a four-day period, from Thursday to Sunday; the number of MEPs elected from a political party is proportional to the number of votes it receives; EU citizens resident in another EU country can vote and stand for election there; each citizen can vote only once.

A lack of transnational lists means that the election campaigns are, to a large extent, national affairs. There have been attempts at reforms but, for now, the elections “are mainly national elections for the European Parliament, instead of truly European elections”, Laura-Kristine Krause of More in Common Germany told Clean Energy Wire.

EU citizens who move to a neighbouring member state can choose to vote there under certain conditions. In practice, however, it is still mostly Polish citizens who vote Polish politicians from Polish parties into the European Parliament, Latvians who vote for Latvians, and Portuguese citizens deciding who of their fellow citizens is sent to Brussels. This means that 27 very different election campaigns firmly rooted in the national contexts will decide the make-up of the next European Parliament.

Still, there are currently ten European political parties which operate transnationally, such as the conservative European People’s Party (EPP) or the European Green Party. However, these are not on the ballots in the elections. They are mostly alliances of national parties with the same political leanings. Most national parties are affiliated to a European-wide political party. The European parties nominate lead candidates for the role of Commission president, but past elections have shown that there is no guarantee one of them will eventually get the job. After the last election, member state governments proposed Ursula von der Leyen for the post, although she was not a lead candidate.

Note: The political parties should not be confused with the political groups in the European Parliament. Membership in one often goes hand in hand with membership in the other, and parties work in close cooperation with the corresponding political groups. However, an MEP who is not member of the European Green Party could still be a member of the parliamentary group Greens/EFA. A political group rallies the MEPs of various member states together with the same political leanings. In some cases, several parties join together in one group.

Focus on the election and the next legislative period

- Political parties in the member states and at EU level appoint their lead candidates and decide their election campaign programmes by early 2024.

- The official campaigns then run until the election in June, and May can be considered the peak month of the EU election campaign.

- Following the election in June, the European Parliament is set up, including the formation of parliamentary groups, and decisions on which lawmakers join the relevant committees.

- Around the same time, the European Council proposes a candidate for European Commission president (taking into account the election outcome) and agrees a “Strategic Agenda for the EU” – a document with policy priorities.

“It's officially the role of the European Council to set the high-level political direction of the EU, so this document has a key role in shaping the Commission’s agenda for the next five years,” explains E3G’s Escrig. Building a climate-neutral, green, fair and social Europe was one of four priorities in the 2019 agenda by the European Council.

- The designated Commission president will then present general priorities to parliament (“political guidelines”) – a key moment for journalists and the public to find out about the EU agenda 2024-2029. Parliament then elects the Commission president. There is currently only one session scheduled for before the summer break this year so it remains to be seen whether parliament elects a new president already between 16-19 July, or in the first session after the break (16-19 September). It is seen as rather unlikely that the Parliament can constitute itself, elect its own president and then the new Commission president all in the same week.

- In the summer, the president of the European Council (the member state leaders) and the EU High Representative (responsible for EU’s foreign and security policy) will be appointed by the European Council. As current president Charles Michel has decided to abandon earlier plans to run for parliament, he is set to remain in his position beyond the June election date.

- Next team of commissioners: The member states propose the commissioners-designate in close cooperation with the new Commission president. Each designated commissioner faces tough committee hearings – and possible rejection - in the European Parliament. This would force the relevant member state and the Commission president to decide on an alternative. The hearings take place during committee weeks in Parliament, with the earliest possibility at the end of July (if a Commission president is already elected at that time), then after the summer break in early September.

- Once all designated commissioners get the green light in the hearings, the European Parliament votes on the entire new team of commissioners so that it can take office. The 2019-2024 Commission took office on 1 December 2019.

- The Commission president then presents so-called mission letters to all commissioners, which explain their mandate and priorities.

“These mission letters are THE documents shaping the concrete Commission work programme and priorities for each department,” says E3G’s Escrig.

The letters represent a treasure trove for journalists planning their coverage for the coming months and years, containing details on planned legislation, and sometimes crucial events.

The elections are still several months away and many things can happen that shift voters’ attention away, but polls show that climate and energy are set to play important roles for voters in many member states. However, as the European Union - like much of the world - is facing multiple crises and uncertainties, there are few signs of a repeat of the 2019 “climate election”. Researchers do not expect climate and energy to be stand-alone topics.

In a recent EU election survey, citizens named action against climate change as one of the top four priorities they want the European Parliament to tackle, tied with supporting the economy and beaten only by the fight against poverty and improving public health. The recurring Eurobarometer poll shows that many in the EU still see climate change as one of the most important issues facing the union, but immigration and international conflicts like the war on Ukraine are higher on the list. Still, it is clear that fears over rising energy prices and the cost of living have been at the front of people’s minds over the past two years. Parties competing in the EU elections must show they are able to alleviate these concerns.

The extent to which energy and climate will play a role in the election campaigns will also vary widely depending on the situation in the member states. Twenty-seven very different election campaigns firmly rooted in national contexts will decide the make-up of the next European Parliament. Many member states such as Croatia, Austria and Portugal also face national elections this year, changing the dynamics of the EU campaigns.

In Poland, the vote is a first test for the overall performance of the new government. Italy is set to focus on issues surrounding the G7 summit it hosts just days after the elections, while Germany might still be grappling with the fallout of its budget crisis and general economic woes. And in France, commentators expect the EU vote to be a barometer for the next presidential election in 2027.

A recent survey analysis by the ECFR divided voters into different groups depending on which of five major recent crises they said most changed the way they look at the future. ECFR said that the "existential traumas" of people experiencing the climate crisis, the financial crisis, the migration crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war would strongly influence how they vote. For people in France, Denmark and Switzerland, climate change is the most important of five major crises, while voters in Germany selected immigration as the issue that most concerns them.

Beyond the campaign, there are several issues which are likely to feature in the next Commission’s agenda for the coming years. First and foremost, policymakers and researchers are calling for a follow-up to the union’s green growth strategy of the past four years. They say a “European Green Deal 2.0” should focus more on industrial policy and finding a way for the EU to secure its place in the world in the green tech race of the coming decades.

E3G’s Escrig says the 2024-2029 EU climate agenda “will most likely feature as part of other emerging priorities, which we see are security, competitiveness, investment needs, social fairness and institutional reform – all of them are also critical areas to successfully implement and build on the European Green Deal.”

Another major policy debate revolves around a new interim climate target for the year 2040. The union has a target for 2030 and aims to be climate-neutral by 2050, but has yet to decide on an interim goal, as required by the climate law. The Commission presented a proposal on 6 February, but the debate will last for months, and a final decision will be up to the next Commission, Parliament and the member states.

Clean Energy Wire has put together a European climate and energy expert database, including policymakers, researchers, NGOs, and many contacts from EU-wide organisations and institutions.

You can find more contacts in the factsheets Covering the EU’s “Fit for 55” package of climate and energy laws and Who sets the targets? Expert Q&A on European energy and climate policy. You can also use the Brussels Binder database to find a woman expert on EU policy.

Finally, you can always get in touch with the team at Clean Energy Wire (info@cleanenergywire.org). We will provide information and connect you with the experts you are looking for.

- Europe Elects aggregates polls from across the EU and provides valuable background information on the elections.

- The blog Der (europäische) Föderalist by researcher Manuel Müller analyses key aspects of the EU system, such as the European electoral law and the European party system (English and German).

- Also check out Politico’s Poll of Polls site.

- Clean Energy Wire has published a whole package of EU election coverage with contributions from several countries. This includes the timeline of European climate and energy policy to keep up to speed on what’s next, and the ‘CLEW Guide to…’ series which provides a general overview over where the various countries stand on energy transition and climate policies. You can also sign up to our weekly newsletter to get CLEW’s “Dispatch from…” – weekly updates from Germany, France, Italy, Croatia, Poland and the EU on the need-to-know about the continent’s move to climate neutrality.

- Niels Timmermans, spokesperson of the current Belgian EU Council presidency, has put together essential information for journalists who cover the coming months.

- The election results will be reported live on the European Parliament's website.

- The European Parliament itself has published an election “Press Tool Kit”. It organised a web briefing on 22 February to give journalists an overview over the process, developments and events, and where to find relevant information.

- You can also contact the Parliament's press service for more information and services. Try getting in touch with the press officers in your member states, who can also support your trip to visit the European Parliament in Strasbourg or Brussels.