CLEW Preview: Cash-strapped German government faces uphill climate action battle in 2024

Energy and climate have been the defining policy areas for German chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition government since it took office – and potentially will remain its performance benchmark in 2024. Confronted with the shock of Russia’s war on Ukraine and the related European energy crisis right after its inauguration, the government initially received acknowledgement for its successful avoidance of an energy shortage and its resolute preparation of a boom in renewable power expansion. However, two years down the road the public mood swung towards frustration over a series of technical policy errors that threaten to undermine some of the main climate and energy policy achievements of Scholz’s administration. Two rulings made by the country’s highest court epitomised the coalition’s fateful relationship with climate and energy policy, which Scholz’s Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party and the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) had made a cornerstone of their term in office.

The first one blocked the quick passage of a law on decarbonising the heating sector in the summer. The law was seen as crucial by the economy ministry under Green minister Robert Habeck, but caused a loud controversy among policymakers and the wider public over fears regarding the financial impact of having to replace gas and oil heating systems in the near future. Habeck ultimately abandoned plans for a ban on new fossil heaters in 2024 and increased subsidies for replacements to soothe voters amid a drop in the coalition’s popularity. But a second ruling in November dealt an even much larger blow to the government’s plans, as the court found that tens of billions of euros earmarked for climate and energy transition projects had been booked unlawfully and violated the country’s ceiling on new credit, the so-called debt brake. This forced the coalition to quickly reshuffle the budget for 2024. Nearly 13 billion euros will be deducted from the special Climate and Transformation Fund (CTF). Until 2027, spending through the fund will be cut by 45 billion euros.

The government thus enters the new year with a heavy baggage regarding its energy transition and climate action plans. This is compounded by deepening economic woes that, in turn, are closely related to high energy prices and uncertainty over the sustained competitiveness of industrial companies. Funds set aside within the CTF were supposed to alleviate the situation and even if the government vowed not to back off on core aims of its green industrial transformation policies, the budget reshuffling means it will have to meet these goals with considerably less money available. A massive protest by farmers and agricultural companies on the streets of Berlin in December against subsidy cuts for vehicle taxes and diesel fuel used in agriculture may have foreshadowed a wider wave of discontent.

Austerity measures also include widely felt changes to climate policy tools, such as an end to electric vehicle purchase premiums and a higher national price for CO2 emissions in the buildings and transport sectors. This means most people in the country will be affected by the budget cuts one way or another, which is likely to give opposition parties ample opportunity to exploit public dissatisfaction. The Christian conservative CDU/CSU alliance, which filed the lawsuit that pulled the plug on the government’s fundings plans, already vowed to take the government to court again if Scholz’s administration plans to circumvent the debt brake by declaring an emergency in 2024. Despite the opposition party eagerly exploiting the government’s own goal in the context of the debt brake ruling, Friedrich Merz’s CDU might ultimately agree to find some sort of compromise with the government on securing funds for urgently needed investments in infrastructure and industry.

However, advocates of stronger climate action arguably worry less about possible quarrels between the government parties and the CDU/CSU than about the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD). Having made substantial gains in two western state elections and polling strong across the country in late 2023, the populist party, which rejects most energy transition policies and outrightly denies that there is need for climate action, is eager to repeat and even leverage its success in the EU elections in mid-2024 – and even more so in three eastern German state elections in September, where it is set to blame citizens’ financial worries on decarbonisation measures and on the end of fossil fuel trading with Russia. In Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia, the AfD can legitimately hope to become the strongest party and is certain to at least heavily influence public debates and government policies there. If Scholz’s coalition government was given a difficult start by the energy crisis and geopolitical tensions, its third year in office looks set to also become a difficult one for its political leadership – but this time due to a homemade crisis.

The EU elections and several votes in eastern German states will put the government’s climate policy to the test following two years of crisis-mode policymaking and budget woes due to the landmark constitutional court ruling. The government must begin to align the national carbon price on transport and heating fuels with the new EU ETS II. It has said it would present a report on this by the end of 2024. After a pause in crisis year 2023, the national price is set to rise from 30 to 45 euros per tonne, and while this translates to only a few cents per litre of petrol or diesel, interest groups’ call for the ‘climate bonus’ (Klimageld) that would return revenues to citizens are getting louder.

- March: the 2023 emissions data will likely show that a weak economy continues to be the main driver of falling emissions in Germany

- 30 June: Germany must submit final national energy and climate plan (NECP) to EU

- Throughout the year: expect debate about going beyond net zero emissions to gain traction, also linked to Germany’s role in helping reach a future 2040 EU climate target

The EU elections, the forming of a new leadership and the adoption of its policy programme for 2024-2029 will dominate the European Union agenda next year. Voters will head to the polls on 6-9 June, and then it will take several months until a new Commission is formed towards the end of the year. In the past four years, the European Union has transformed key areas of its climate and energy legislation as part of the Green Deal – Europe’s strategy to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. The next EU executive will have to ensure that the 27-member bloc moves from words to action to implement an ambitious policy and to assert itself as the global climate leader it aims to be, while safeguarding its economy in transition against global competition. One key issue will be deciding an emissions reduction target for 2040, based on which the next big round of legislative reforms will be based. Polls repeatedly show that voters see climate change as a key threat facing the continent and the bloc, even as the green transformation is becoming increasingly politicised. Climate action, such as rules on how people heat their homes or which mode of transport they use, increasingly influences citizens' daily lives.

- Early 2024: new Polish government to present key policy proposals

- 6-9 June: EU elections

- 6 February: European Commission to present proposal for 2040 climate target and communication on industrial carbon management

- Summer & autumn: forming of a new EU leadership

Russia’s war against Ukraine and war and terror in the Middle East have shown that geopolitics can quickly influence Germany’s climate and energy policy, whether it speeds up the transition, slows it down or pulls attention away. With 2024 as a global super election year – votes in the U.S., India, the EU and in many other places all have the potential to shift power – it is unclear where the world will be one year from now.

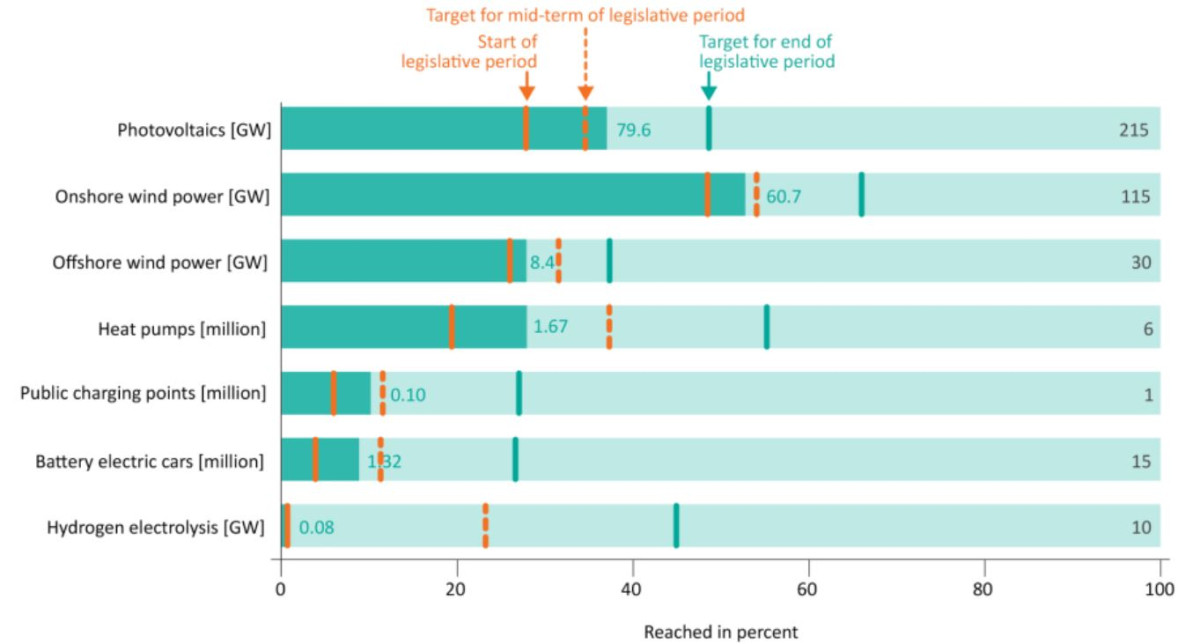

Speeding up the transformation of Germany’s power system towards 100 percent renewables has been a key promise of the government since it took office in late 2021. The results of its efforts after two years give reason for optimism that the 2030 interim target of a renewables share of 80 percent in electricity production can be reached – and they are backed by reaching the milestone of more than 50 percent renewables in the power system throughout the entire year of 2023. Yet, there still are significant hurdles on the way.

Expansion of solar PV capacity is making good progress across the country, while that of onshore and offshore wind still leaves much more to be desired, according to the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW). “The energy transition’s speed has to be increased significantly to meet Germany’s climate action commitments,” the institute said in an analysis published in late 2023.

In the past two years, solar PV capacity has grown by 20 gigawatts (GW) to 80 GW, equalling a substantial increase of about 33 percent. However, given the government’s targets of 105 GW by late 2025 and 215 GW by 2030, the rapid buildout must be further increased in 2024 and beyond to an annual average of 18 GW to stay on track. Not least due to the impact of the energy crisis, solar PV expansion in the past year has been driven especially by smaller roof-mounted installations that offer savings potential and feed-in remuneration to investors. The government has enacted policies throughout 2023 that are supposed to boost expansion of larger open-field solar farms and on commercial buildings that will have to show an impact in 2024 if the ambitious targets are to remain feasible.

For onshore wind, the capacity increase has been a much more modest 5 GW to a total of 61 GW at the government’s midterm. The government has aimed to add another 15 GW in the coming two years to reach 115 GW, which means that a substantial annual increase to 7 GW of added capacity is needed. Through a wide range of measures that the federal government agreed with Germany’s 16 state governments, onshore wind investors are supposed to meet much fewer bureaucratic hurdles and planning uncertainty in the next years when entering new wind farm projects. A higher licensing quota for new projects and a doubling of auctioned volumes provides some confidence that the targets can be met, the country’s grid agency (BNetzA) said in December – even though the last onshore wind auction of the year once again ended undersubscribed.

The situation is even more difficult regarding offshore wind, where only 0.6 GW has been added since the end of 2021. Longer planning and preparation periods complicate a sudden surge in new installations at sea. But the more than 8 GW of new offshore turbines that were successfully auctioned throughout 2023, in which bidders were ready to pay a fee for entering the auction, at least suggest that a doubling of the current capacity of just under 8 GW could be in the offing in the next years, the DIW said.

“The set targets can be reached if all initiatives launched during the first two years of the government’s term of office are continued resolutely during the second half,” the researchers concluded. However, the current financing difficulties resulting from the constitutional court’s ruling are likely to complicate these efforts, they added. “It has become more important than ever to use all support funds as efficiently and in a target-oriented way as possible,” the DIW found.

Like many other sectors of Germany’s economy, industry is entering the new year burdened with an economic downturn, elevated energy prices and a skills shortage. However, the government and most companies remain determined to make progress on industry decarbonisation in 2024 – not least because they consider the global energy transition an enormous business opportunity. The energy crisis also forced many energy-intensive enterprises to think about ways to reduce their fossil fuel dependencies as they struggled to adapt to new price levels and intensified calls for speeding up the rollout of renewables and a “hydrogen economy” in close coordination with EU industrial policy. Industry will have to lower emissions from around 160 million tonnes of CO2 in 2022 to 118 million tonnes by 2030 to be in line with government targets. The country must act quickly to secure its place as a key location for industries in an increasingly climate-friendly global economy, according to economy minister Habeck.

- The government agreed in November to support companies struggling with high electricity prices in the coming five years with a package of measures worth 12 billion euros in 2024 alone, including a lower electricity tax and an expansion of existing subsidy schemes – thereby shelving Habeck's proposal for a capped industry electricity price. Industry associations welcomed the package and said it would help strengthen Germany as a business location. The plan largely survived the ensuing budget debacle, but energy prices will remain one of industry’s primary concerns in 2024.

- Discussions about the need for additional industry subsidies are set to continue within and outside the government in 2024. The EU and Germany launched a big push to make green industries less dependent on imports, especially from China. Germany already supports the energy subsidiary of engineering conglomerate Siemens, and the economy ministry signalled it also plans support for domestic solar PV manufacturing. But in light of the government’s ongoing budget crisis, finance minister Lindner also questioned the need for generous state support to attract investments in future industries, such as battery, hydrogen or semiconductor production.

- Germany will continue its rollout of “pioneering” Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfDs) to compensate companies for the higher operating costs of low-emission investments, and initial industry demand for the scheme exceeded expectations. Many companies will also be affected by the trial period for the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which started in October.

- The implementation of Germany’s updated hydrogen strategy will remain closely watched in 2024. The government wants to ramp up electrolysis capacity to 10 GW by 2030, which would require increasing existing capacity – which has barely increased recently – around 100-fold. It also decided to build a “hydrogen core grid” measuring 9,700 kilometres by 2032, which is estimated to cost 20 billion euros.

- Hydrogen and other decarbonisation technologies are set to feature prominently at Hannover Messe,” one of the world's largest industry fairs, which will take place in late April under the title “Energising a sustainable industry.”

Germany did not make much headway in 2023 to lower transport emissions, which have been stagnant for decades. But time is running out rapidly to get on track for the sector’s climate targets: Emissions will have to fall from almost 150 million tonnes of CO2 in 2022 to 85 million tonnes by 2030. The shift to electric cars is a central step in this endeavour: The government wants to have 15 million electric cars on the country’s roads by 2030. The clean mobility transition is not only a huge challenge for the country’s mighty car industry, but will also require big improvements in public transport. Additionally, it involves difficult just transition issues, ranging from job losses in combustion technology suppliers to affordable transport costs, which could quickly come to the fore in 2024.

- The uptake of low-emission cars has recently stagnated, with the share of electric vehicles - including plug-ins - at roughly one quarter of new registrations in 2023. Following the budget crisis, the government abruptly ended its electric car subsidy programme in December, fuelling doubts whether the 15 million target can be reached. Clean mobility experts say the government must be on guard in 2024 and act quickly if sales veer further off track.

- Germany’s railways are in a sorry state, with delays and cancellations spiralling. The failings were discussed widely in the media, creating pressure to improve reliability with comprehensive renovations in 2024.

- As a measure to help struggling households during the pandemic, Germany introduced a flat-rate ticket for regional and local public transport. But future funding for the so-called “49 Euro Ticket” hangs in the balance, as federal and state governments are quarrelling over financing.

- There are growing concerns about the social dimensions of the clean mobility transition, with mobility experts calling for measures to counter “mobility poverty” as high energy prices have pushed up transport costs.

- The EU will agree on new emission rules for heavy duty road transport in 2024. The IAA Transportation trade fair in Hanover in September is set to showcase the rapidly growing number of battery-electric trucks, which appear to become the sector’s low emission technology of choice.

The heavily debated law on the gradual phase-out of fossil fuel boilers will enter into force at the turn of the year. Media described the controversies within the coalition government and society about how to achieve climate-friendly heating as "one of the greatest political dramas in recent German history." Following the fallout of the heating law, the government is likely to tread carefully around new policies covering the decarbonisation of the construction sector. Plans to increase the energy efficiency requirements of new buildings from 2025 have already been shelved, as the country also faces a housing shortage and falling orders.

- The step-by-step de facto ban on new fossil heating systems kicks off in 2024. For now, only new buildings in areas of new residential developments are effectively banned from installing new gas and oil boilers.

- The price of CO2 for heating fuels will go up in 2024 from 40 to 45 euros per tonne of CO2-equivalent, according to the latest government agreement. This would make heating oil around 5 cents per litre more expensive, and natural gas 0.4 cents per kilowatt hour.

- The government aims to install 500,000 new heat pumps annually from 2024. Additionally, the coalition also aims to build 400,000 new homes each year. However, it failed to meet this target last year and this year, and construction minister Klara Geywitz refused to promise that it will be met in 2024 or 2025.

- A national circular economy strategy, set to be published in 2024, should set the framework for reducing raw material demand and consumption in the construction sector.

- It is yet unclear to what extent the budget crisis will hit government funding for climate-friendly new builds or energy efficiency renovations.

- Germany's building sector has continuously missed its emission reduction targets.

Germany is discussing a reform of its electricity market as it strives for a renewables-driven power sector. This will have to be coordinated with the EU's own reform, which was agreed between regulators just before the end of 2023 after months of negotiations. In 2024, the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) is set to substantially increase the number of permits to build planned electricity transmission lines needed for the shift to a climate-neutral energy system, yet debates around fairer grid fees and a split of Germany's power price zone are set to gain prominence in the new year.

- Grid operators in Germany will be allowed to temporarily throttle electricity supply to heat pumps and electric vehicle charging points to maintain grid stability from January 2024. In return, distribution grid operators will have to offer reduced fees and will not be allowed to refuse or delay the connection of new heat pumps or charging stations, arguing that possible bottlenecks could arise with the new installations.

- By the third quarter of 2024, the BNetzA will reach a decision on a redistribution of grid fees to reduce costs in areas with a high share of renewables – the current system has been criticised by northern states as an effective penalty for their renewable energy expansion efforts.

- The economy ministry should swiftly present the long-awaited power plant strategy (Kraftwerkstrategie in German), which is set to introduce a tender system to ensure new (hydrogen-ready) gas-fired power plantsare built. The government sees the 24 GW of controllable power production capacity as a necessary supplement to renewables to secure electricity supply as Germany phases out coal. Yet the publication has been postponed for the foreseeable future as a result of the budget crisis. Industry leaders have said a much longer delaythreatens to jeopardise the target of an early 2030 coal phase-out in the country, as the plants take around six years to build.

- Germany's government has been in talks with transmission system operator (TSO) TenneT since the end of 2022 to buy the German subsidiary of the Dutch power grid operator. The purchase was not completed in 2023, but could go through in 2024.

- In 2022, EU electricity market regulator ACER gave Germany's four TSOs 12 months to conduct the bidding zone review, examining whether to split the country's single price zone for electricity. The publication of the report examining ACER's recommendations was delayed and is now scheduled for publication in December 2024.

When Germany shut down its last three nuclear power reactors in April 2023, critics of the phase-out warned that this would lead the country to increase the use of coal-fired power production. At the end of the same year, it turned out that the use of lignite fell to the lowest level since 1965. Between July and September alone, coal power use overall dropped nearly 50 percent compared to the previous year. While the drop has partly been caused by lower energy consumption due to depressed economic output, it indicated that fears over a sudden and substantial revival of the fossil fuel because of the nuclear exit were overblown.

However, this does not mean that all indicators point to the success of the government’s plans to pull forward the country’s coal exit from the official 2038 end date to 2030. State governments in eastern Germany have repeatedly voiced their concerns about or even outright rejected an earlier exit. They argue that this could both undermine supply security in the country and cause havoc in coal mining regions that lack sufficient time to wean local economies off the fossil fuel. Finance minister Christian Lindner from the FDP, who has repeatedly acted as a sceptic of more ambitious climate policies, openly questioned whether an earlier coal phase-out is feasible as long as no secure and affordable alternatives are put in place.

To make matters worse, even the western coal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with which economy minister Habeck has already brokered a deal for a 2030 phase-out, has started to question the plans. State premier Hendrik Wüst, who hails from the conservative CDU that is in opposition at the federal level, said that delayed planning for a substantial capacity of hydrogen-ready gas plants that could substitute the coal plant fleet threatens the agreed earlier end date in the heavily industrialised state. The government will thus have no time to lose in 2024 to make progress on implementing its modern gas power plant construction plans to keep its vision of an earlier coal exit credible. But whether the government’s “ideal” phase-out schedule can be kept will also depend on the pace of renewable power and grid expansion. An evaluation of the coal phase-out’s progress and prospects has been planned for release in late December after months of delay.

Germany must step up its climate adaptation efforts as it faces prolonged droughts, severe water loss and increasing warming. According to a recent report by the Federal Environment Agency (UBA), it is one of the regions with the highest water loss worldwide. Germany passed a law to make adaptation legally binding in 2023 – the first framework for climate adaptation at all administrative levels in Germany. The country must now use this momentum to step up implementation, especially around the areas of heat protection, drought and wildfires, experts say.

- The climate adaptation law requires the federal, state and local authorities to address climate risks and develop appropriate strategies. By September 2025 at the latest, the federal government will have to present a strategy with clear and binding targets to deal with the effects and risks of climate change.

- Germany introduced its first federal heatwave plan in 2023, aimed at preventing heat-related deaths. The initial focus was on communication and awareness-raising, but with shareholder talks in spring, the federal health ministry aims to introduce structural changes to better prepare the country against heat in the summer of 2024 and beyond.

- With the EU Taxonomy and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), many larger European businesses are now facing at least two reporting standards that will require them to analyse how the impacts of climate change are affecting their bottom line.