Q&A: The “stress test” - what kind of nuclear runtime extension is Germany debating?

1) What is the current status of nuclear power in Germany?

2) Why did the debate about extending the nuclear plants’ runtime come up?

3) What is the grid “stress test” good for?

4) Could it mean the nuclear phase-out is reversed?

5) What could a longer use of the remaining reactors look like?

6) What do plant operators say?

1) What is the current status of nuclear power in Germany?

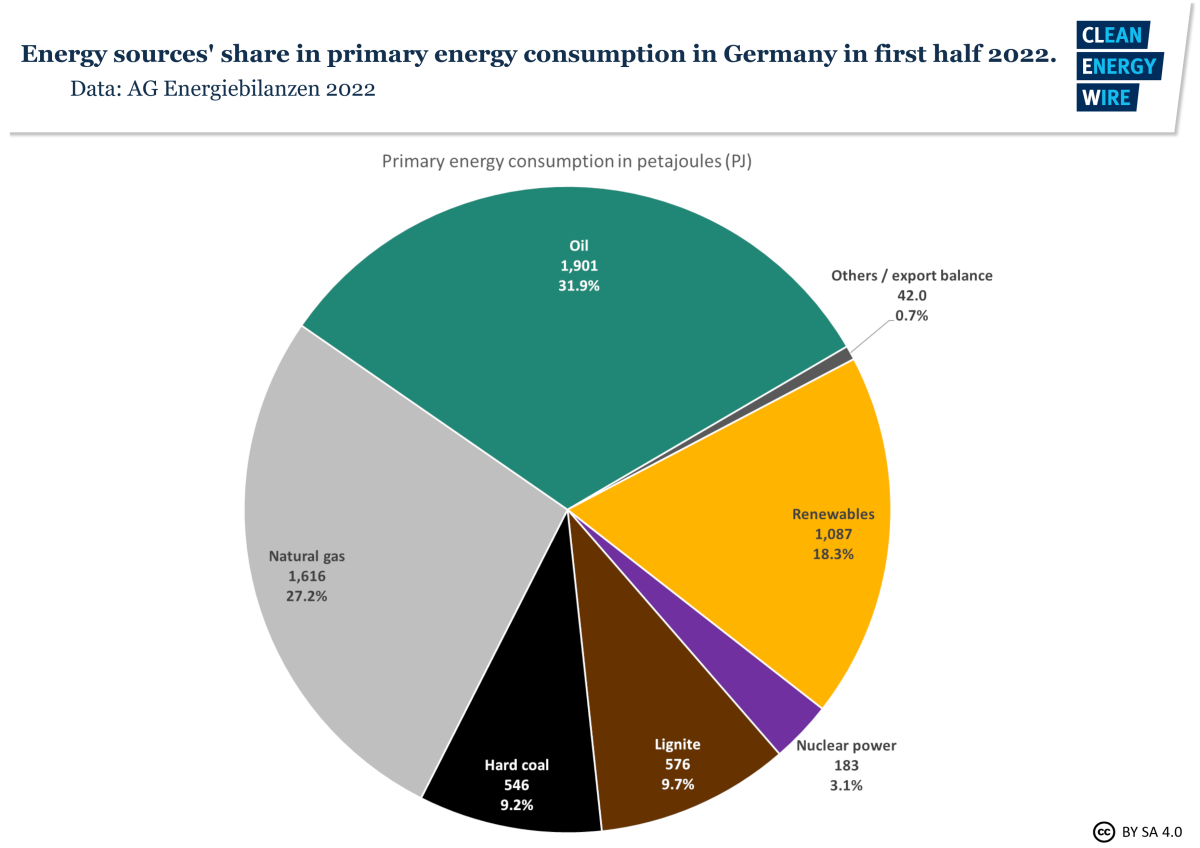

The nuclear power exit, which originally was decided in the year 2000, is currently scheduled to be complete by the end of 2022. The phase-out timetable, agreed on in the nuclear exit law, so far has been followed as planned, leaving only three plants on the grid as of 2022: Isar 2 in south-eastern state Bavaria, Neckarwestheim 2 in south-western Baden-Wurttemberg, and Emsland in north-western Lower Saxony. Current legislation says that all three plants will be taken off the grid by 31 December this year, and their operators have accordingly made preparations to phase-out their reactors and start dismantling them in line with the schedule. The plants covered three percent of Germany’s energy consumption in the first half of 2022.

2) Why did the debate about extending the nuclear plants’ runtime come up?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine quickly raised the spectre of a severe energy supply crisis in Germany and Europe. In particular, the supply of fossil fuels like coal, oil and especially natural gas from Russia were expected to continually dry up over the course of the war in Ukraine. In a bid to assess the resulting risks to the stability of Germany’s energy system, the economy and climate ministry (BMWK) immediately after the start of Russia's attack conducted a “cost-benefit analysis” for all available energy sources, to show how such alternatives could be used to compensate for dwindling supplies from Russia.

While the government found that greater use of coal-fired power plants could help to cushion the impact, it concluded at the time that prolonging the use of nuclear power is unadvisable, as reactors couldn’t make any meaningful contribution to stabilising the energy system. Refuelling problems mean the plants could only produce additional electricity for a few months into 2023. Moreover, only a small share of gas is actually used in power production – it is instead mostly used for heating buildings and in industry – and flexible gas power plants are often only used to provide electricity during certain peak demand periods, which is something that nuclear plants cannot do.

However, politicians from the opposition conservative CDU/CSU alliance and also from the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) in the government coalition contested the ministry’s conclusion, arguing that every kilowatt hour of gas saved would help. This was also a view shared by several of Germany’s EU partners, who argued that the country’s plea for solidarity regarding gas supplies was inconsistent with its plans to shut down a reliable power source in the middle of an energy crisis. Calls for a limited extension also came from industry representatives and local politicians from across the board, who argued nuclear power could contribute to grid stability under certain regional circumstances. Surveys also showed that the attitude towards nuclear power in German society had softened in response to the energy crisis, with a clear majority saying the reactors should keep running at least for a limited period of time to help cope with the energy crisis. In late July, the government responded to such calls and announced it will carry out a second assessment of the benefits of extending the runtime of specific plants in the "stress test."

3) What did the grid “stress test” analyse?

The test was conducted by Germany's four transmission grid operators, 50Hertz, Tennet, Amprion and TransnetBW, over the course of several weeks was designed to determine whether Germany will have sufficient electricity production capacity with the nuclear plants going offline at the end of the year. Unlike in the first analysis, it took into account several developments on energy markets that followed on from Russia’s invasion. These include the current skyrocketing gas prices and their effect on electricity demand - for example the surge in the use of electric heaters; the re-activation of coal plants from the country’s stability reserve; and the status of gas supply from other sources as well as storage filling levels. It also factored in the additional strain on Germany’s power system resulting from power exports to France, which struggles to maintain power system stability despite its vast nuclear plant fleet due to maintenance problems and a Europe-wide drought that complicates reactor cooling and coal supply by inland shipping.

The test found that "crisis-like situations in the power system for some hours are very unlikely in the winter of 2022/2023 but cannot be ruled out entirely at the moment," meaning Germany could not be certain of receiving enough energy from abroad in case of a shortfall. Even though it was "very unlikely" that such a situation occurs, not having so-called re-dispatch capacity from plants abroad could become a challenge especially for southern Germany, where a lack of renewable power and grid capacity expansion had left the power system particularly vulnerable. The grid operators concluded that it made sense to use all options for increasing power production and transmission capacities in the coming winter, recommending to keep all three remaining plants in the emergency reserve. However, as the Emsland plant in the north is not as important to local grids as the two other plants in the south, the “political decision” to take the Emsland plant offline as planned would be acceptable from a technical point of view, 50Hertz head Stefan Kapferer said.

4) Could it mean the nuclear phase-out is reversed?

The stress test result means that Germany will stick to the nuclear phase-out as regulated by law, said economy and climate minister Robert Habeck. New fuel elements would not be loaded, and the new reserve would be ended by mid-April 2023. "Nuclear power is and will remain a high-risk technology and the highly radioactive waste will burden many generations to come," he said.

Advocates of nuclear energy ahead of the test result's announcement had called for a substantially longer expansion and restock nuclear fuel rods to prepare for several years of continued operation. Some even suggested the nuclear exit should be scrapped altogether. The calls were led by the conservative opposition alliance CDU/CSU. The CSU, which has been governing the southern economic powerhouse state Bavaria for decades, became particularly adamant that the government consider an extension for the Isar 2 plant. The state is very exposed to shortfalls in natural gas supplies, and has also failed to build up sufficient renewable power capacity in the past years to reduce its fossil fuel dependence.

Finance minister Christian Lindner from the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) meanwhile suggested Germany could completely overhaul its energy strategy and re-introduce nuclear power long-term. He renewed his calls for letting nuclear plants run until at least 2024 shortly before the stress test's results were announced. However, chancellor Olaf Scholz had also ruled out that the nuclear exit as a whole would be put into question. This rejection is shared by a majority of his Social Democrats (SPD) and also by the Green Party. A general reversal of Germany’s nuclear phase-out decision therefore continues to be very unlikely.

5) What could a longer use of the remaining reactors look like?

The plants, Isar 2 in Bavaria and Neckarwestheim 2 in Baden-Wurttemberg, should be put on standby for until mid-April 2023 after the scheduled end date on 31 December this year to possibly “contribute in certain stress situations in the power grid,” the economy ministry said after the stress test's results were revealed. The Emsland plant in northern Germany should be decommissioned as planned, however. The proposal by Habeck's ministry must now be debated by the government and by parliament, as legislative reforms are necessary. The FDP and also the CDU/CSU opposition both said they would strive to expand the standby mode to all of the three remaining plants.

The economy ministry's proposoal means the two plants in the south would effectively go offline and only be reactivated to produce electricity if other instruments are not sufficient to avert a supply crisis in Germany's industrial south. This mean energy production with nuclear plants would not increase total energy production in a significant way and it does not entail the procurement of new nuclear fuel rods. The minister said he does not expect plants to be turned off and on several times. If the country decided to keep the plants online during the coming winter -- a decision which could already be taken in December -- then the plants would run continuously until April. Following intensive monitoring of the power supply situation, the economy ministry would propose to give the plants a limited runtime extension. The grid agency would then recommend to get them out of the reserve. The final decision is then to be made via government decree with the possibility of objection by the parliament.

6) What do plant operators say?

The remaining plants’ operators, energy companies E.ON (Isar 2), EnBW (Neckarwestheim 2) and RWE (Emsland), have shown little enthusiasm for changing their phase-out plans since the onset of the debate, but signaled they would try to find ways to make it work if necessary. EnBW said a “limited” extension is feasible, while RWE head Markus Krebber in June called the debate futile, arguing that “the hurdles are high and the contribution to saving gas is too small.” E.ON, whose Bavarian plant is the most likely to receive an extension, meanwhile said it is “open to discussions.” However, CEO Leonhard Birnbaum said there are “no plans for continued operation of any kind.” The framework conditions for such a move were not known, with no figures on actual production requirements available.

Reactors would have to run somewhere between three and five years longer to make investments in staff and infrastructure pay off, while necessary security checks would further complicate relying on the nuclear plants as a quick fix. Likewise, the companies and also the government expect a wave of litigation in the case that the intricate nuclear phase-out law, which carefully regulates residual power production, nuclear waste management and financial accountability, is amended. It is still unclear who would be held accountable for additional nuclear waste and reduced safety standards in the event of a runtime extension. The last time the country’s nuclear exit law was changed, with a runtime extension ordered by the coalition of Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the FDP in 2009, the amendment was taken back two years later after the Fukushima disaster - a move that cost German taxpayers billions of euros.