Germany’s carbon pricing system for transport and buildings

A carbon price in Germany has increased consumers’ bill for fuels such as petrol and diesel by several cents per litre since the beginning of 2021. The German government in 2019 adopted its fuels emissions trade law (Brennstoffemissionshandelsgesetz - BEHG), which introduced a CO₂ price on fuels used predominantly for heating and transport.

Germany, like all EU member states, participates in the European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), which sets an overall limit on greenhouse gas emissions from power stations, energy-intensive industries (e.g. oil refineries, steelworks and producers of iron, aluminium, cement, paper and glass) and intra-European commercial aviation. The ETS is one of a growing number of carbon pricing initiatives worldwide.

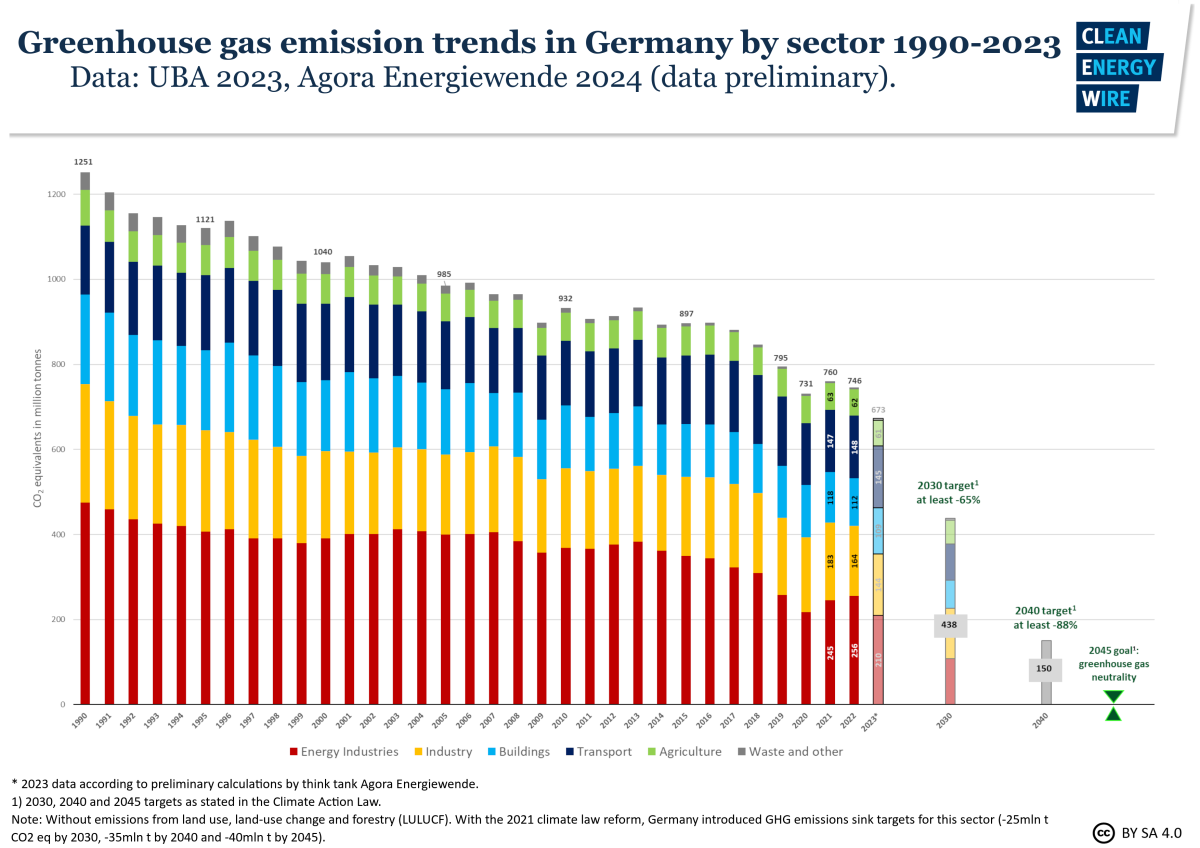

Until 2021, however, greenhouse gas emissions from the transport and building heating sectors had no German or EU-wide price. The two sectors largely rely on fossil fuels, such as heating oil, natural gas, gasoline and diesel. These sectors were responsible for more than a third of Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2022.

The national emissions trading system for transport and heating fuels will exist in parallel with the EU-wide ETS and cover the bulk of the greenhouse gas emissions not included in the ETS. There will be some overlaps where fuels are already covered in the ETS, but will also be priced in the new system. The law already stipulates that companies will be reimbursed, and an additional regulation is meant to avoid the need for companies to pay twice in the first place.

In 2022, natural gas and diesel each accounted for around a third of reported emissions in the system, followed by petrol and heating oil, each accounting for around one sixth of emissions.

The new system is going to be a ‘cap and trade’ system in which the federal government sets an annual total emissions limit for transport and heating fuels in line with its annual total non-ETS targets prescribed by the European Union. The EU Effort Sharing scheme prescribes annual greenhouse gas emission budgets for all non-ETS sectors combined. However, these also include emissions that do not come from burning transport and heating fuels, such as methane emissions in agriculture. Those will not be covered by the planned German system.

Emission allowances are transferable and can be traded. They will generally be auctioned. However, during an initial phase there will be a fixed price at which they are simply sold to companies (2021-2025).

The federal government says the system’s implementation will cost companies about 31 million euros annually due to increased bureaucracy and necessary infrastructure installations.

The responsible government organ is the Federal Environment Agency (UBA).

From 2027, the national CO2 price will be replaced by the EU ETS II (running separately from the existing EU ETS), which includes emissions in the buildings and transport sectors (more below).

What and who will be priced?

- transport and heating fuels, such as petrol, diesel, heating oil, natural gas and coal

- covers heating emissions in the buildings sector and of energy and industry facilities not covered by the EU ETS

- covers transport emissions except for air transport

- does not cover non-fuel emissions (e.g. methane in agriculture)

- participants are not the emitters themselves, but companies that put fuels into circulation or suppliers of the fuels (upstream approach)

- government says this means about 4,000 companies will participate

- to avoid a double burden from the national system and the ETS, fuel deliveries to ETS facilities are exempt from the national price; where this leads to disproportionate administrative needs, there will be compensation

The price

- fixed price in 2021: 25 euros per allowance (tonne of CO2 equivalent) [means around 7 cents price increase for litre of petrol, 8 ct/l of diesel]; 2022: 30 euros; 2023: 30 euros,

- 2024: 45 euros [around 8.4 cents price increase for litre of petrol, 9.5 ct/l of diesel]; 2025: 55 euros

- in 2026 in auctions, with a price corridor of 55- 65 euros

- from 2027: market price, with option for price corridors (to be decided in 2025)

Following the German government's budget crisis in December 2023 and in a bid to consolidate reformed budget plans, the ruling coalition decided to increase the CO2 price from the planned 40 euros to 45 euros from January 2024. For 2025, the Social Democrats (SPD), Green Party, and pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) agreed to increase the price to 55 euros per allowance, from the planned 45 euros.

Flexibility

- during fixed price/price corridor phase: should the emissions budget not suffice and targets in non-ETS sectors be missed, Germany would use the flexibility of the EU Effort Sharing scheme – this could include buying emission allocations from other member states

Revenues

- government expects the new system to generate revenues of 40 billion euros in 2021-2024 (period of budget planning at the time). In 2023, proceeds from the national CO2 price jumped 67 percent to 10.7 billion euros, compared to 2022.

- revenues will go into the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF), which is used, between others, for energy-efficient building renovation and boiler replacements, renewable electricity feed-in support, the rollout of electric mobility infrastructure and the nascent hydrogen industry, as well as relief measures for citizens and industry, and for climate action support programmes.

Emissions reduction

- based on projections, the government expects the price to save 3.1 million tonnes of CO₂ in 2025, 7.7 t in 2030 and 12.4 t in 2035

Carbon leakage risk

- following some delay, the government decided a carbon leakage regulation to accompany the CO2 price legislation in March 2021 and updated it in July to take into account parliament criticism. The regulation ensures compensation for the carbon price for certain companies in international competition to prevent climate-harmful industry from simply moving abroad. Compensation under the regulation is tied to climate action investments by the companies

- a study by German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) says the new carbon price system does not contain a high risk of carbon leakage

Citizen support

- in its coalition agreement, the ruling coalition said it would introduce a "climate bonus" (Klimageld in German) to pass on revenue from its national carbon pricing scheme to citizens. Government party policymakers have now cast doubt on whether the plan to introduce the bonus payments could be implemented, given that a constitutional court ruling causing Germany’s budget crisis at the end of 2023 had “severely restricted” the government’s financial scope.

- in July 2022, the government scrapped the EEG levy, a landmark mechanism that funded renewables expansion via power bills for more than two decades, with the aim of reducing electricity costs for households. The government moved to support renewable power with the proceeds from emissions trading and the state budget.

After deciding to increase the 2030 EU greenhouse gas reduction target, the bloc has moved to underpin the new ambition with measures and instruments. In January 2023, the European Union decided on a new emissions trading system to cover fuel distribution for road transport and buildings, and additional industrial sectors. The system will run separately from the existing EU ETS, and will fully launch in 2027, with the market forming the CO2 price (instead of it following a fixed price as is the case in Germany now).

It is currently unclear how high the price per tonne of CO2 will be once the European system starts, although experts expect a significant increase. Think tank Agora Energiewende has urged the government to quickly devise a plan on how to regulate and manage the start of the scheme, and to put measures in place to deal with a possible jump in prices. Instruments which were set up by the EU to keep the price in check are unlikely to be enough to guarantee avoiding a sudden jump in fuel prices, said Simon Müller, director for Germany at the think tank. This was because climate action in transport and buildings was lagging far behind in many countries, including Germany, he said.

Germany’s government coalition of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats had for years shunned the debate about introducing a price on CO2 emissions in these sectors, often for fear of upsetting voters, businesses or industry. However, a drought in the summer of 2018 and the Fridays for Future student climate protests pushed climate action to the forefront of the political debate and increased pressure to consider carbon pricing as a central measure to mitigate global warming and bring Germany back on track to reaching its emissions targets.

In this environment and after months of talks, the former coalition government presented a comprehensive climate policy package on 20 September 2019 that included the outline for a national trading system for greenhouse gas emissions from burning fuels in the transport and buildings sectors.

In the months of talks leading up to the climate package decisions, the coalition parties heatedly debated whether to introduce a tax on CO2 emissions – favoured by the SPD – or a national trading system for emissions allowances, called for by the CDU/CSU. The eventual proposal of a trading system with fixed allowance prices in the first several years is a mix of the two approaches.

In October 2019, the cabinet adopted a first draft of the National Emissions Trading System for Fuel Emissions Law. It was adopted by the Bundestag with minor changes, and the Bundesrat gave the green light on 29 November, thus clearing the last hurdle for it to take effect.

However, after other aspects of the government’s climate package became part of negotiations in the mediation committee of the Bundestag and the Bundesrat, the price was tabled yet again. The Green Party – which is part of most state government coalitions – called for an increase. In a preliminary agreement from 16 December, lawmakers decided to amend the already adopted law and increase the price. The price increase was adopted by the Bundestag in October 2020.

For an overview of the various parties' and experts’ positions on carbon pricing, as well as the developments leading up to the government’s comprehensive climate package decisions from 20 September 2019 see our article "Tracking the CO2 price debate in Germany".

Originally, the government had proposed (and parliament adopted) a lower price, from 10 euros in 2021 to 35 euros in 2025, which was heavily criticised by experts and institutions, such as the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC). They and a large group of stakeholders ranging from business associations to environmental NGOs had criticised the low entry-level price in 2021 and the following years. This would “hardly have a steering effect,” the MCC said, adding that long-term planning and investment security was lacking as the price post-2026 would only be determined in 2025. The carbon price would thus only have a limited effect on investments and innovation.

The German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) said in an assessment of the CO2 pricing effects that it would burden poor households more than rich households in relation to net income. Despite planned relief via a decrease in the renewables levy and an increase in the commuters’ allowance, the pricing system would lead to additional revenues for the state, the DIW said. Keeping a national CO2 price "socially fair" had been one of the government’s main arguments for starting with a price of only 10 euros per tonne.

The new government from 2021 promised a "climate bonus" (Klimageld in German) in its coalition agreement. This would constitute of support payments to citizens as the government increases the national price on carbon emissions in the transport and heating sector. However, following a constitutional court ruling causing a budget crisis at the end of 2023, government party policymakers had cast doubt on whether the plan to introduce the bonus payments could be implemented, as the resulting budget gap “severely restricted” the government’s financial scope. An alliance of environmental organisations, as well as government advisors, have continuously urged the government to pass on revenue from its national carbon pricing scheme to citizens.

Due to a compromise based on the demands of the government coalition partners, experts say the CO2 pricing system could face severe legal hurdles. As the proposal foresees the eventual creation of a trading system, but a fixed price during the early years – which Christian Lindner, head of the pro-business FDP party, calls “a CO2 tax in disguise” – a debate has erupted about the legal foundation for a price on emissions.

A legal opinion by the Institute for Applied Ecology (Öko Institut), published ahead of the final decision for the mixed system, points out that Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court previously made it clear that an upper cap for emissions is necessary for a trading system to be deemed in line with German law. The current draft states that should the cap be exceeded during the early years of the system, Germany would buy additional allocations from other EU member states.

Without “substantial” changes, the planned CO2 price carries a “concrete risk of unconstitutionality,” Thorsten Müller, chairman of the Foundation for Environmental Energy Law (Stiftung Umweltenergierecht), wrote in a message thread on Twitter after the draft law was presented in October. Müller argued that a fixed price in a trading system would not be an admissible levy, adding that the government proposal does not meet the requirements for other forms of fees, such as a CO2 tax.

Legal experts told Carbon Pulse in early 2021 that they expected lawsuits to be filed. A first lawsuit was being prepared and was set to be filed by mid-2021, reported Tagesspiegel Background in March.