When will Germany finally ditch coal?

The role of coal in the German economy is perhaps the most crucial and hotly debated issue in the country’s fight to lower greenhouse gas emissions. Coal remains central to Germany’s power system, providing 42 percent of gross power production in 2015 – 18 percent from hard coal and 24 percent from lignite. The carbon-heavy fuel is the main reason the power sector is responsible for over a third of the country’s CO2 emissions.

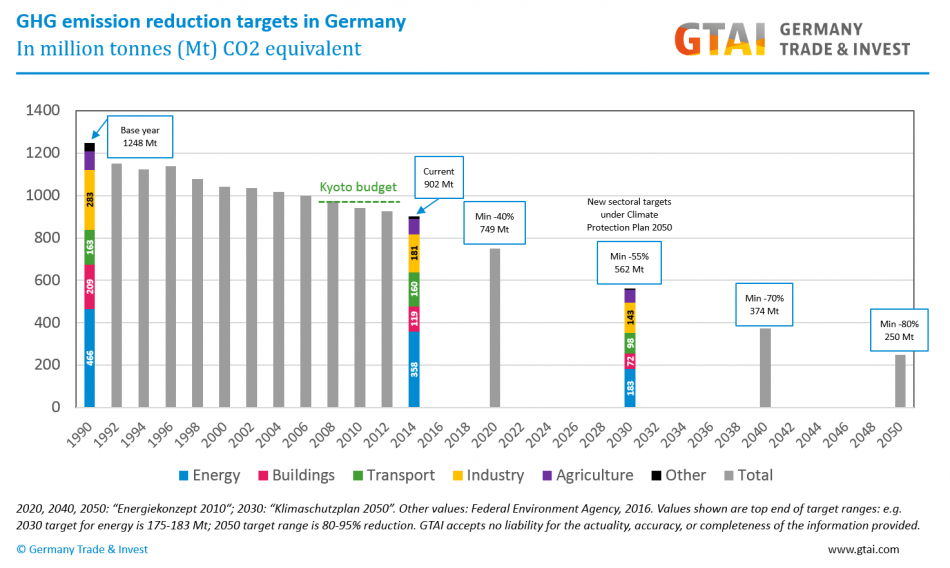

After months of wrangling, the German government finally passed its Climate Action Plan 2050 detailing how the country is to uphold it commitments under the Paris Agreement and become virtually carbon-neutral by 2050.

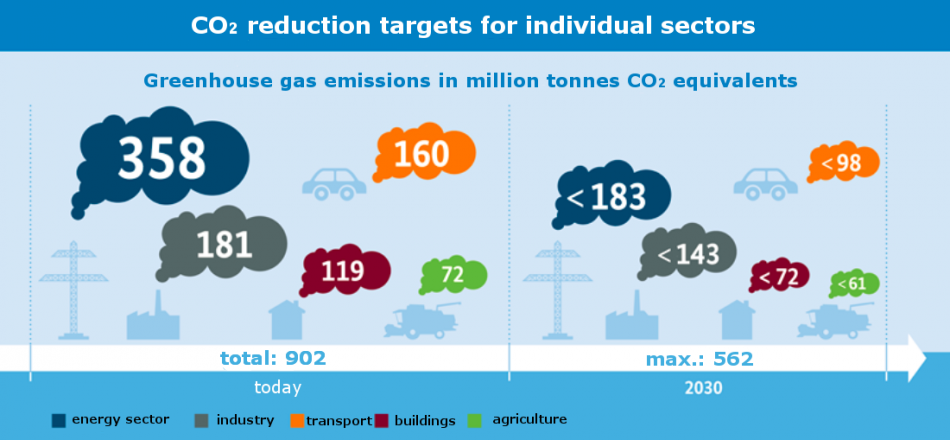

The plan put emissions-reduction targets in place for different sectors of the country’s economy. The energy sector will have to halve its current greenhouse gas output by 2030, to less than 183 million tonnes. Environment Minister Barbara Hendricks says this implies that half of Germany’s coal-fired power plants will have to be switched off by 2030.

Emissions from industry and agriculture that are considered unavoidable will likely eat up Germany’s entire CO2 budget available to Germany by mid-century. That means electricity, transport, and heating will have to run without causing any emissions whatsoever – i.e. be powered solely by renewables.

Environmentalists see the plan’s failure to set a deadline for the last of Germany’s coal-fired power plants to be switched off as its biggest weakness.

The Energiewende paradox

Over recent years, German electricity production from coal has barely budged. The growing supply of electricity from renewables, which has close to zero marginal costs, has driven down wholesale power prices.

That’s pushed relatively climate-friendly but expensive natural gas out of the market and given a competitive advantage to coal – and cheap, domestically mined lignite in particular. Low prices for CO2 allowances under the European Emissions Trading System mean coal’s environmental impact has not made it less economically competitive.

The surge in renewables and ongoing coal power production has also led to an oversupply of electricity, pushing up power exports. Almost 8 percent of electricity generated in Germany last year was used in neighbouring countries.

These developments have led to the so-called “Energiewende paradox”: Germany’s rapid development of renewable power has barely dented CO2 emissions.

Abroad, the phenomenon is sometimes blamed on Germany’s decision to exit relatively climate-friendly nuclear power, but analysts say the real reason for the paradox is the shift from gas to coal.

A tough habit to kick

The use of coal for power production has a long history in Germany. Mined domestically, it powered the German Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle) after World War II.

Unable to compete with imports from abroad, Germany’s hard coal production fell almost 90 percent between 1990 and 2013 and has long been propped up state subsidies. But following a legal battle with the EU, the German government agreed to end these subsidies and shut down the last of its hard coal mines by 2018.

Lignite, meanwhile, is still mined on a large scale in opencast pits, mainly in Lusatia in the very east of the country, and North Rhine-Westphalia in the west. Because lignite is humid and heavy, it’s too expensive to transport over long distances, and is burned in nearby power stations, which top the list of Europe’s largest CO2 emitters.

There are a number of reasons why phasing out lignite is easier said than done:

- Lignite mining provides a significant number of jobs in the affected regions, though the overall number of people working in jobs directly linked to lignite has dropped to around 20,000 in Germany overall. Particularly in economically weak Lusatia, it is far the biggest employer and there are few alternative job opportunities. Thus, the “losers” in a coal exit are highly concentrated.

- They are also well organised, because mining employees are represented by the powerful union IG BCE, a staunch and influential defender of coal mining.

- A further complicating political factor is that lignite-mining regions are in states considered strongholds of the Social Democrats, a party with strong union links, meaning local governments have resisted addressing the issue head-on.

- Utility association BDEW says there is a complicated interplay between lignite mines and power stations. They can’t be operated independently, as power plant closures directly affect the mines and vice-versa.

- According to German Trade Union Association DGB energy expert Frederik Moch, plant closures would have additional far-reaching effects on the local economy. He cites the example of a paper mill, which is directly connected to one of Lusatia’s power stations.

Climate Action Plan falls short of exit date

Environment Minister Hendricks insists that a coal exit is implied in the Climate Action Plan 2050. “If you read the Climate Action Plan carefully, you will find that the exit from coal-fired power generation is the immanent consequence of the energy sector target,” she said.

Yet the plan remains vague on detail. It says, “climate targets can only be reached if coal-fired power generation is reduced step-by-step.” But due to strong resistance by mining unions, as well as regions economically dependent on coal, it omits a specific date for the last coal station to go offline.

An earlier draft included plans for a commission to devise the country’s exit from coal. But the final draft refers only to setting up a commission for “Growth, Structural Change and Regional Development” to discuss the transformation required by climate protection. Its job description does not even contain the word “coal”, much less a terminal date. Moreover, it won’t start work before 2018.

“The climate action plan touches on a coal exit, but doesn’t call it by name. A clear exit path, which would allow for the creation of new opportunities for employees and the affected regions, is missing,” laments Christoph Bals, head of environmental NGO Germanwatch.

Bill Hare, head of climate science and policy institute Climate Analytics, still insists “the targets of the plan lead to a coal exit. The signal is clear.”

Off-target in 2020

Environmentalists are emphatic that immediate action is needed on coal, because it is so crucial to Germany's long-term targets – and also because it might be the country's last chance to reach its 2020 target of reducing CO₂ emissions by 40 percent compared to 1990.

The government has already set in motion a host of measures to get nearer the target, such as 2014’s Climate Action Programme, the National Action Plan for Energy Efficiency (NAPE), and the 2015 decision to take 13 percent of the country’s lignite power producing capacity offline and transfer it into an emergency reserve.

Regardless of these efforts, environment ministry projections show Germany will only reach 2020 targets in an unlikely best-case scenario. Germany would have to switch off around 15 large coal plants, and make similar efforts in the transport sector, according to an evaluation of legislative changes by Agora Energiewende.

Given the challenges ahead for Germany’s Energiewende once the Paris Agreement comes into force in 2020, Regine Günther, former climate expert at WWF Germany is concerned Germany might get off on the wrong foot. “We must not start the race in debt,” she said at a hearing by the parliamentary commission on economics and energy.

Günther is also adamant that Germany should switch off some of its coal plants before 2020. “It would be a huge contribution to reaching the climate targets. And the coal plants are not even needed in Germany, because the power is exported,” she said.

In December 2016, the Green Party published a plan to put the country back on track for its 2020 goals, with shutting down coal fired power plants to contribute the largest share of emissions savings, at 78 millions tonnes of CO2 equivalents.

Reversing the paradox

There are tentative signs that power production from coal might already be declining. In the first nine months of 2016, hard coal and lignite use each dropped by around 4 percent, while natural gas went up by almost 7 percent, according to first estimates by energy market research group AG Energiebilanzen (AGEB).

“It seems that the trend has not only stopped, but is beginning to be reversed,” Agora Energiewende head Patrick Graichen told the Clean Energy Wire. Lignite will continue to be used for power generation. This year’s market-related effects will not be enough for Germany to reach its climate targets. But they show that not a whole lot of political effort is needed as lignite becomes less and less economically viable.”

Some German utilities have already announced plans to decommission coal-fired generating units, because they are no longer economically viable.

Because of these developments, Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND) climate expert Antje von Broock says that from a long-term perspective, “a lignite phase-out exit is already underway” in Germany. Speaking at the at a Climate-Alliance event, she pointed out that the lignite sector now employed around 20,000 people, compared to around 150,000 in 1990.

It is also debatable whether climate protection justifies fixation on an exit date. According to scenarios by think tank Agora Energiewende, the key question is not when the last lignite plant closes, but rather when the large majority of plants will be taken off the grid. This has a larger effect on cumulated CO2 emissions than an end date. However, the think tank believes that while setting a deadline may not be a scientific necessity, it is vital as a political tool and to remove uncertainty as coal-fired plants are shut down in stages.

So when will Germany finally switch off coal?

Given these complications, it remains entirely uncertain Germany will finally go coal-free – with most guesses ranging between 2030 to 2050. And even most environmentalists do not demand the plants be switched off within the next 10 years.

Germanwatch’s Bals believes a socially acceptable coal exit in Germany is possible by 2030, while WWF’s Günther says Germany must switch off its last lignite plant in 2035 at the very latest.

Energy and climate expert Claudia Kemfert of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) called an end to coal by 2040 “indispensable” during the parliamentary hearing.

Energy state secretary Rainer Baake says a phase-out in the early 2040s is the most likely scenario. “When I look at the stakeholders’ positions, it seems to suggest that the last [coal] power station will likely go offline between 2040 and 2045.”

Energy Minister Sigmar Gabriel also said it was unlikely Germany’s last lignite power plants would go offline before the 2040s: “Lignite will definitely not be switched off in the coming decade. And I don’t believe that it will happen in the decade after that, either.”

Energy-intensive industry opposes a rapid phase-out because it is concerned this will push up costs and undermine international competitiveness.

Carsten Rolle, who heads the energy and climate department at the Federation of German Industries (BDI), insists the coal exit is already implied by the European Emissions Trading system (ETS), and therefore does not need to be specified by German legislation.

“We already know today that in the course of the 2040s, coal power stations won’t be able to operate because the emissions trading system won’t permit it,” Rolle said during the parliamentary hearing.