Coronavirus crisis highlights risks of U.S.-European LNG deals diplomacy

“The Coronavirus is a global crisis, not limited to any continent, and it requires cooperation rather than unilateral action.” With this unequivocal statement, European leaders officially “disapproved” of U.S. President Donald Trump’s unilateral decision to impose a travel ban for Europeans in March 2020, which he had taken without consulting EU partners.

It marked yet another low point in transatlantic relations which policy experts say had been “in intensive care long before the coronavirus appeared.” And it showed clearer than ever that Europe – while shortly thereafter also closing its borders and limiting exports of some medical equipment – takes issue with a U.S. leader who flagrantly promotes his ‘America First’ policy at home, disregarding long-held norms of international diplomacy, particularly towards close allies.

EU officials long struggled to find the right tone vis-à-vis an often impulsive and unpredictable president. Climate and energy policy were no exception – they failed to keep Trump from pulling out of the Paris Agreement or imposing sanctions on the Russian-German natural gas pipeline Nord Stream 2.

The current crisis deepens and accelerates this trend, said Kirsten Westphal, senior associate at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) – one of the country’s most influential think tanks, which advises the government, national parliament and German officials in international organisations. “The EU and the US are on completely different tracks with regards to energy and climate policies,” she said. While Europe wants to maintain its pledge for a Green Deal – also as a reference for a recovery programme after the Covid-19 crisis – the United States is still sticking to is “energy dominance” vision, she told Clean Energy Wire.

Since Donald Trump took office and put his country on a path diverging from the decades-long close ties with European allies, transatlantic relations have worsened.

A survey by the Pew Research Center found that the president receives largely negative reviews from publics around the world, with especially negative sentiments in Western Europe. Roughly three-in-four or more lack confidence in Trump in Germany, Sweden, France, Spain and the Netherlands.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace recently interview European ambassadors and deputy ambassadors based in Washington, D.C., most of whom said the transatlantic relationship is in a worse state under the Trump administration than at any other point in recent history, including after the United States’ contentious decision to go to war with Iraq in 2003. The diplomats name climate change as one of the key contentious policy fields.

The existence of man-made climate change – as well as deciding ways to combat global warming – has been a point of contention at countless international meetings over the past two and a half years, either bilateral or at G20, G7 and UN summits. While Trump has called climate change “a hoax” devised by the Chinese, turned his back on multilateral climate action and decided to leave the Paris Agreement, the European Union aims to become the first climate neutral continent by 2050 and is currently devising its roadmap to get there – the European Green Deal.

Germany has been a particular target of the Trump administration’s criticism on energy and threat of car industry tariffs. At the July 2018 NATO summit, Trump lashed out at the contentious Russian-German natural gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 being built in the Baltic Sea, saying Germany is and will be “totally controlled” by the former Soviet states’ oil and gas supply. When Trump repeated his claims in the UN General Assembly, German diplomats in the room – including foreign minister Heiko Maas – appeared to laugh at the President.

In an effort to smooth such tensions over the past two years, the European Commission has highlighted significant growth in liquefied natural gas (LNG) trade with the United States as a key success story of transatlantic energy cooperation. Even before the coronavirus crisis, policy experts warned such attempts to use LNG sales as a kind of diplomatic tool are built on a shaky foundation, as they depend on economics in a free market at any given time. Changes in the global LNG market as the virus spreads could prove them right sooner rather than later, as the pandemic is projected to cause a devastating global recession.

U.S. officials have made no secret of their strategy to use LNG as a tool in diplomacy. It has become a regular topic of debate in bilateral talks with foreign governments.

During his keynote address at the major energy conference CERAWeek in Houston in 2019, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said he wanted U.S. gas producers “working in tandem with American diplomats” to “create stability and prosperity” across the globe. According to his plan, American diplomats would “work to ensure that markets are open for American businesses all around the world.” He said the country’s businesses would “certainly benefit financially”, but efforts were also about supplying energy security to partners and safeguarding American national security. “It’s about Russian influence peddling and the need to stop it. We must bring this to an end,” Pompeo told oil and gas industry representatives in the room.

Trump has criticised other countries that “use energy as a weapon of coercion” and the president’s administration touts the country’s own LNG as a “no-strings-attached” supply. In an interview with Clean Energy Wire, Shawn Bennett, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Oil and Natural Gas at the U.S. energy department, said: “To Europeans the LNG gives them an option to get a supply that is not tied to any political pressure that may be applied regarding piped gas.”

However, the current U.S. government is using and politicising gas in a way that it disapproves of when other countries do the same, for example in trade negotiations.

The supply of natural gas gets caught up in the political winds, said Samantha Gross, fellow in the Cross-Brookings Initiative on Energy and Climate. “Unlike in other parts of the world, our supply is not in the hands of government, and that is an advantage to us and the world,” the former government official told Clean Energy Wire. Thus, the country is actually not set up to use its resources politically. “However, this particular president has really wanted to do that,” she said of Trump. “He views energy as a tool that he can use in his trade negotiations.”

One of the most striking example of this art-of-the-deal LNG diplomacy during Trump’s tenure so far was a joint statement with then-European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker following a White House meeting in July 2018. For months, Trump had threatened to introduce tariffs on European cars. To ease the growing threat of a transatlantic trade war, Juncker promised the bloc would import more LNG from the U.S. In turn, Trump would refrain from imposing car tariffs. Later, German economy minister Peter Altmaier said the country would speed up the process to build its first LNG import terminal as “a gesture to our American friends” after the president had criticised Germany for its dependence on Russian gas and the construction of Nord Stream 2.

To overcome these tensions on climate and energy, Europe and the United States have put a focus on LNG trade – in which both say they see benefits. For the U.S., it is one piece of the puzzle forming Trump’s vision of U.S. “energy dominance” – making the country a global energy superpower. LNG exports create jobs for Americans, reduce trade imbalances and replace Russian gas or Chinese coal across the globe. EU officials say natural gas will remain an important component of the Union’s energy mix in the near future as it moves towards cleaner sources of energy. The liquefied U.S. gas is a welcome alternative for example to Russian pipeline gas as domestic production declines – if the price is competitive.

In early 2019, German economy minister Peter Altmaier invited U.S. officials and gas industry representatives from both countries to an LNG investor conference in Berlin, and the EU followed suit with a similar conference in May, providing “U.S. and European decision-makers from companies in the LNG sector with match-making and deal-making opportunities”, as a press release said.

Still, the German government makes clear that beyond facilitating dialogue in this way, it leaves business decisions to companies in a free market. The diversification of energy supply is “an important concern” of the German government and the EU, and both pipeline gas and LNG can contribute to this, the economy ministry in Berlin told Clean Energy Wire. However, in the end “decisions regarding the import of natural gas are taken by private companies.”

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s current government alliance of CDU/CSU and SPD agreed in its coalition treaty to make the country “an LNG infrastructure location”. The economy ministry said it welcomed plans to build German LNG import terminals, as the phase-out of domestic European gas production and the coal exit would lead to increasing demand for imports, “initially of natural gas and in the medium term of synthetic gases and hydrogen.” However, “the final investment decisions […] will be made by private investors,” it said.

Gross criticises such tit-for-tat. “If in government negotiations you look at everything as a business transaction – you scratch my back, I scratch yours – that’s not how we should wield power.”

While both the European and German governments see gas as an important fuel during the energy transition, a big question is how much the continent needs and for how long. With the goal of climate neutrality by 2050, fossil fuels are bound to be phased out almost completely. Falling domestic gas production will increase the need for imports, but total demand is projected to remain at a comparable level to today’s.

“If the EU remains serious on the Green Deal, and hopefully it does so as part of a coronavirus recovery programme, LNG is just a bridge and decarbonising gas a must,” said SWP’s Westphal.

The European Union, however, often fails to speak with one voice on energy policy. Natural gas in particular has been a point of contention, nowhere more apparent than in the planned Nord Stream 2 pipeline supported by the German government, but opposed especially by many countries in Eastern Europe.

For countries like Poland – which has been reluctant to commit to the climate neutrality pledge – U.S. LNG is a welcome alternative to Russian pipeline gas. The country’s consumption has grown steadily for the past years. “What is certainly visible in the Polish system is that the importance of gas in the energy mix is growing,” Joanna Maćkowiak-Pandera, president of the Warsaw-based think tank Forum Energii, told Clean Energy Wire.

The country aims to diversify its supply (about half of all natural gas imports came from Russia in 2019) to Norwegian gas and LNG. Several long-term contracts signed in recent years mean that much of the latter will come from the United States. This could in part be the result of Trump’s gas diplomacy. Already during a visit to Poland in 2017 the president had promoted exports, and at the 2020 Munich Security Conference, Mike Pompeo announced one billion dollars in financing to Central and Eastern European countries of the Three Seas Initiative – a forum of Eastern European states to push cross-border energy, infrastructure and digitalisation projects. LNG facilities in Poland, Lithuania and Croatia have been a key focus, with the aim to lessen dependence on Russian supply.

A report by the Atlantic Council says heavy political support from the United States meant the initiative was originally viewed with scepticism by the EU and German governments as a possible anti-EU, U.S. “wedge” project.

“U.S. LNG has been a diplomatic tool, but one that has split the EU – almost as Russian gas did – by promoting a very exclusive approach in the Three Seas Initiative,” SWP’s Westphal told Clean Energy Wire.

At the same time, economics certainly have also played a part for Poland. Contrary to other countries, pipeline gas from Russia is more expensive than American LNG, as Poland has so far paid a higher, oil-pegged price, said Maćkowiak-Pandera.

For her, U.S. supply has key advantages. “Certainly it has its political connotations, but the most important thing is that Poland gained a real diversification option.” It also helps lessen Polish scepticism of natural gas in general, which has slowly started to displace coal, said the think tank head. In any case, American gas, its costs and volume have not been on the front pages of newspapers lately, she added. “It seems that it is not a topic Polish diplomacy is dealing with these days.”

The Trump administration has been very aggressively cheerleading for its industry, for a time even rebranding its LNG as “freedom gas” or “molecules of freedom” which give “America’s allies a diverse and affordable source of clean energy.” The government has since largely stepped away from using these terms. Although it sometimes continues to entertain the same general idea, it also highlights what it sees as the fuel’s other advantages, such as its emissions benefits for countries moving away from coal and providing an option in the European market that helps bring down the price of other suppliers.

In mid-2019, the U.S. government was quickly ridiculed on social media and criticised by U.S. and international press for using the terms “freedom gas” and “molecules of freedom” for U.S. LNG exports in a press release. Greenlighting additional export volumes by Freeport LNG in Texas, the Department of Energy’s Undersecretary Mark Menezes said this step was “critical to spreading freedom gas throughout the world by giving America’s allies a diverse and affordable source of clean energy.”

In December, the Australian company Plain English Foundation voted freedom gas the worst phrase of the year 2019, arguing that “when a simple product like natural gas starts being named through partisan politics, we are entering dangerous terrain.”

The term appears to have been coined during a press conference in Brussels several weeks earlier. Seventy-five years after liberating Europe from Nazi Germany occupation, “the United States is again delivering a form of freedom to the European continent,” said U.S. energy secretary Rick Perry, reported EurActiv. “And rather than in the form of young American soldiers, it’s in the form of liquefied natural gas,” he told reporters on 1 May 2019. “So yes, I think you may be correct in your observation,” he said in reply to EurActiv’s Frédéric Simon, who asked whether “freedom gas” would be a fair way of describing U.S. LNG exports to Europe.

The energy department’s Shawn Bennett told Clean Energy Wire he does not think employing the term was a mistake, but he would not do so. “It was a term that was used by former Secretary Perry. From his perspective, he looked at it as no-strings-attached molecules. We are not using it as a political weapon. […] The U.S. government has no ownership of the molecules or of the projects. What takes place are transactions between private entities.”

While the exact term “freedom gas” might no longer be used by the energy department, the idea still persists. Energy secretary Dan Brouillette in December tweeted “U.S. LNG is freeing our allies in Europe from dependence on Russian gas, increasing their energy independence and strengthening their energy security.”

The energy department’s Bennett explains the administration’s approach as supporting business deals and “educating others countries on transitioning into natural gas for a lower-carbon-emission future. […] As we meet with other countries, it is about talking about the availability of U.S. LNG and its benefits and opportunities,” says Bennett. For example, if countries aimed to build a regasification facility or other infrastructure “we just want to make sure that they know we are there.”

However, the transactional element in diplomacy is set to persist under President Trump, as showcased by the recent Phase One trade deal with China, in which the U.S. promised to cut some tariffs on Chinese goods in exchange for Chinese pledges to purchase more American energy goods.

In private conversations, industry representatives say they appreciate the U.S. administration’s push, but caution that overly politicising gas trade could harm the business. CSIS’s Tsafos says that the U.S. government’s aggressive approach is “a little bit over the top of what business is used to.” Open reactions by companies range from indifference to an embrace of the government’s approach.

“We are a private company, so we react to market signals,” said Alexandre Paty, Vice President Trading of Total Gas & Power North America, a subsidiary of the French multinational energy major. Paty recalls a 2019 Trump visit to an LNG export terminal in Louisiana, where the president gave a speech praising the trade that allows partners to “reduce their dependence on countries who use energy as a weapon of coercion.”

“He was saying a lot of positive things about U.S. LNG exports, but nothing that he said changed the environment in which we work,” Paty told Clean Energy Wire.

Omar Khayum, CEO of Annova LNG – a planned export facility near Brownsville, Texas – welcomes government efforts. He is primarily looking for support in “getting connected and finding solutions to customers’ problems” in foreign jurisdictions. “This administration – politics aside – has been very focussed in embassies around the world on advancing LNG,” he said at a recent conference in Houston. “We’ve had a very positive experience in that regard. It’s what’s necessary and that is what we expect from our government, right?”

In theory, using the carrot-and-stick approach and politicising a commodity carries a cost, Nikos Tsafos, senior fellow at the D.C.-based policy research organisation Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), told Clean Energy Wire. “Having said that, last year was the best year ever for final investment decisions in U.S. LNG projects, despite this politicisation and despite there being a trade war with China.”

He sees one possible explanation in that, “countries might say: if the U.S. values a contract so much, let’s make one and get them off our back. As a product of that, some things happen, even if it feels pushy.”

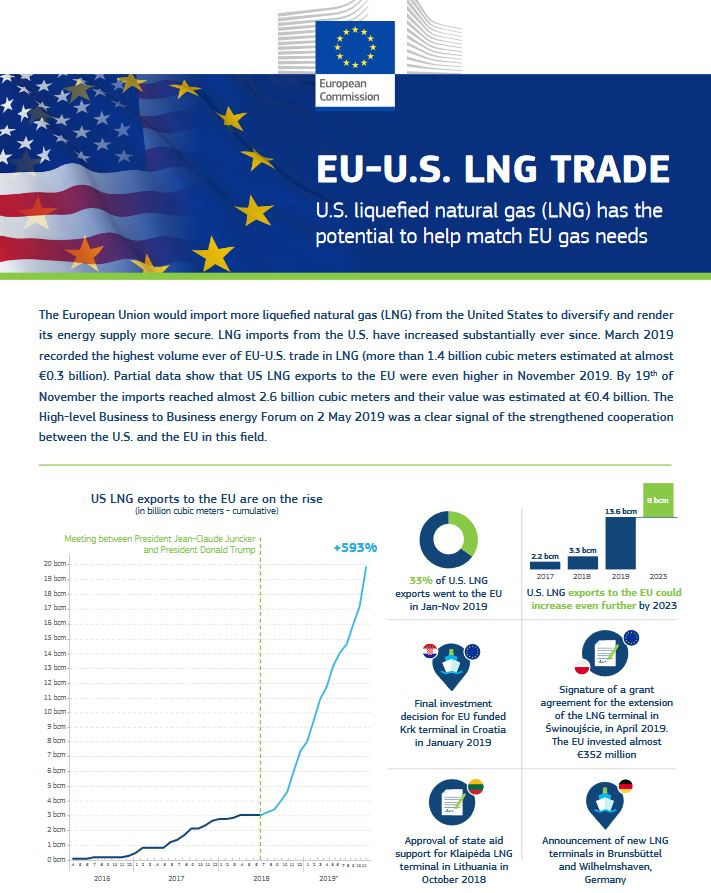

Since the agreement between Juncker and Trump, imports of U.S. liquefied natural gas in Europe have grown much stronger than before.

In a press release, the White House commented on this, saying “thanks to President Trump’s negotiations, the European Union (EU) agreed to import more LNG from the United States.” And the European Commission has highlighted the increase in a regularly updated factsheet on EU-U.S. LNG trade – rather a PR tool than a sober display of the numbers. It contains several graphs on the issue, some more meaningful than others.

From July 2018 to the end of 2019, the cumulative volume of imports increased by more than 600 percent. However, trade back then was at a low level to start with. Only about 30 LNG vessels had arrived before that moment, since the first cargo in April 2016.

Overall, Qatar remains the EU’s biggest source of liquefied natural gas. In 2019, it supplied 30 billion cubic metres (bcm), followed by Russia (21 bcm) and the U.S. (17 bcm). The European Commission’s latest quarterly gas market report states that “in 2019 an increasing competition could be observed between the U.S. and Russia in LNG supply to the EU” – to say nothing of total gas supply: almost 46 percent of EU gas imports (pipeline + LNG) came from Russia in 2019.

Still, the U.S. administration welcomes the increased trade with the EU. “If you look at the past year, Europe was our number one destination for LNG imports, so there has been a significant growth in that market,” said the energy department’s Bennett. “We saw an amazing trend happening with exports moving from Asia over to Europe.” Bennett said he expects the market with Europe will grow.

However, it was not governmental action that drove up European imports, but rather profit, as Reuters reported in early 2019. Prices in Asia fell sharply on lower-than-expected demand, so energy companies switched their sales to Europe.

The EU has become an important destination for U.S. LNG “because of an accident of where the market ended up, not by design,” CSIS’s Tsafos told Clean Energy Wire. Europe has become the absorber of U.S. gas because of its storage and regasification capacity, a sort of “dumping ground for excess LNG”, he added. Juncker and Trump had little influence. “It was perfect timing, but not something that either of them did.” Tsafos warned that the market could switch again if conditions were to change.

“It’s too soon to tell how U.S. LNG exports to Europe will fare over the coming months,” he told Clean Energy Wire in mid-April and added that there are several competing forces which will determine future trade. For one thing, everyone is trying to access gas storage, and Europe is ideally placed to store gas, even if its own inventories are already very high, he said. “So that’s a reason to continue to see U.S. LNG flowing to Europe.”

“On the other hand, the gap between prices in North America and overseas has narrowed, making it less profitable to export,” he said. At the same time, some Chinese companies have been granted exemptions on tariffs for U.S. LNG so some of it is flowing to China, said Tsafos.

Reuters reports that Japan-Korea-Marker (JKM) price for LNG assessed by S&P Global Platts fell to a record low of 1.938 dollars per million British thermal units (mmBtu) on 23 April. "The drop means that the JKM price is now almost at parity with the Henry Hub gas price in the United States, discouraging spot cargo deliveries from the United States to Asia as the coronavirus pandemic dampens global gas demand in an already heavily oversupplied market."

SWP’s Westphal points to what could happen when the impact of the coronavirus crisis starts to emerge in parts of the world affected from the start of the pandemic. “U.S. LNG imports which have exponentially increased over the past months will face losses and probably turn to East Asia if economic recovery starts there again.”

Clark Williams-Derry, energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), agrees that it is too early to tell how the U.S. LNG export business will develop under the coronavirus crisis. Global LNG markets are already increasingly volatile, speculative and high risk, he said. “With the economic turmoil we’re seeing, I think that market participants believe that global demand growth will slow, that global liquefaction capacity will remain in surplus, that global prices will stay low, and that price spikes will be lower than in the past. This doesn’t bode well for new U.S. LNG projects.”

Even the demand situation in Europe is far from set in stone. Gas needs could also grow due to the coronavirus crisis, wrote Jennifer Gordon, managing editor and senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “The European green transition will probably slow down, as surviving the coming recession at any cost will take front seat,” she said. This in return could make Europeans rethink their energy mix. “Natural gas might come out as the winner.”