How many car industry jobs are at risk from the shift to electric vehicles?

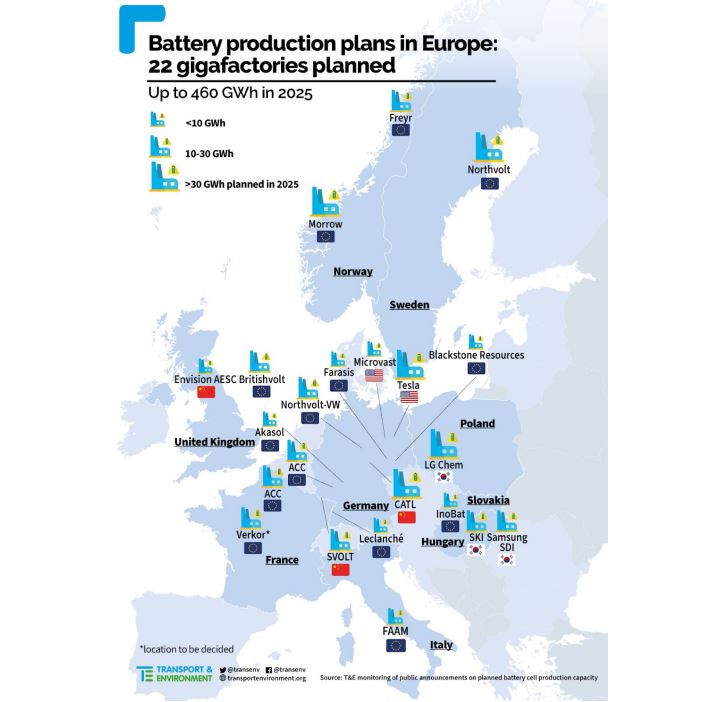

Europe's mighty automobile industry is grappling with the accelerating shift to climate-friendly cars. The list of countries planning to ban the sale of new conventional cars within two decades is rapidly getting longer: Norway, Belgium, India, the Netherlands, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, UK, France, Spain and the US state of California all plan a phase-out within the next two decades. The impact on Europe's economy will be substantial, as millions of people currently earn a living by producing conventional cars and their components. Many of them will have to retrain to adapt to new roles in the production of electric vehicles. Others will lose their jobs, while low-emission mobility offers entirely new job opportunities in the industry, such as battery production.

Europe currently produces 25 percent of all passenger cars and 19 percent of commercial vehicles worldwide, according to the European car industry federation ACEA. The region boasts global car giants like the VW Group (which includes the Volkswagen, Audi, Porsche, Skoda and Seat brands), Stellantis (Fiat, Peugeot, Citroen, Opel/Vauxhall), the Renault Group, BMW and Daimler (Mercedes). These companies are often in the spotlight when it comes to the effects of electrification, but recent evidence suggests that the carmakers will manage the shift to electric mobility with fewer job losses than originally feared.

Europe's massive supplier industry looks set to be more heavily affected, as many smaller companies depend on making parts for combustion engines that will no longer be needed in electric cars – for example spark plugs, fuel injection systems, exhaust systems, gearboxes or fuel tanks. These companies will find it particularly difficult to switch to alternative products.

The size of the problem

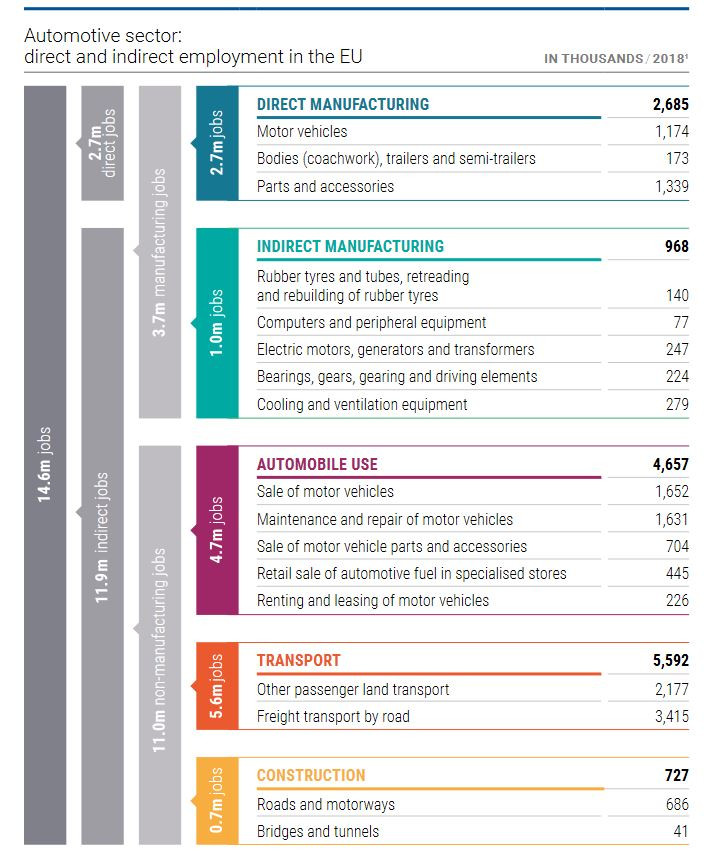

ACEA says that almost 14.6 million people work "directly or indirectly in the auto industry," accounting for 6.7 percent of all EU jobs. But in this figure the lobby group includes jobs at car rentals, petrol stations, road construction, truck drivers and many others that will not be affected by the switch to e-mobility.

Based on data from Europe's statistics office Eurostat, ACEA says that the automotive industry provides some 3.7 million manufacturing jobs - 11.5 percent of all such jobs in the EU. Currently 2.7 million people are directly employed in manufacturing in the automotive industry, corresponding to 8.5 percent of total EU manufacturing employment.

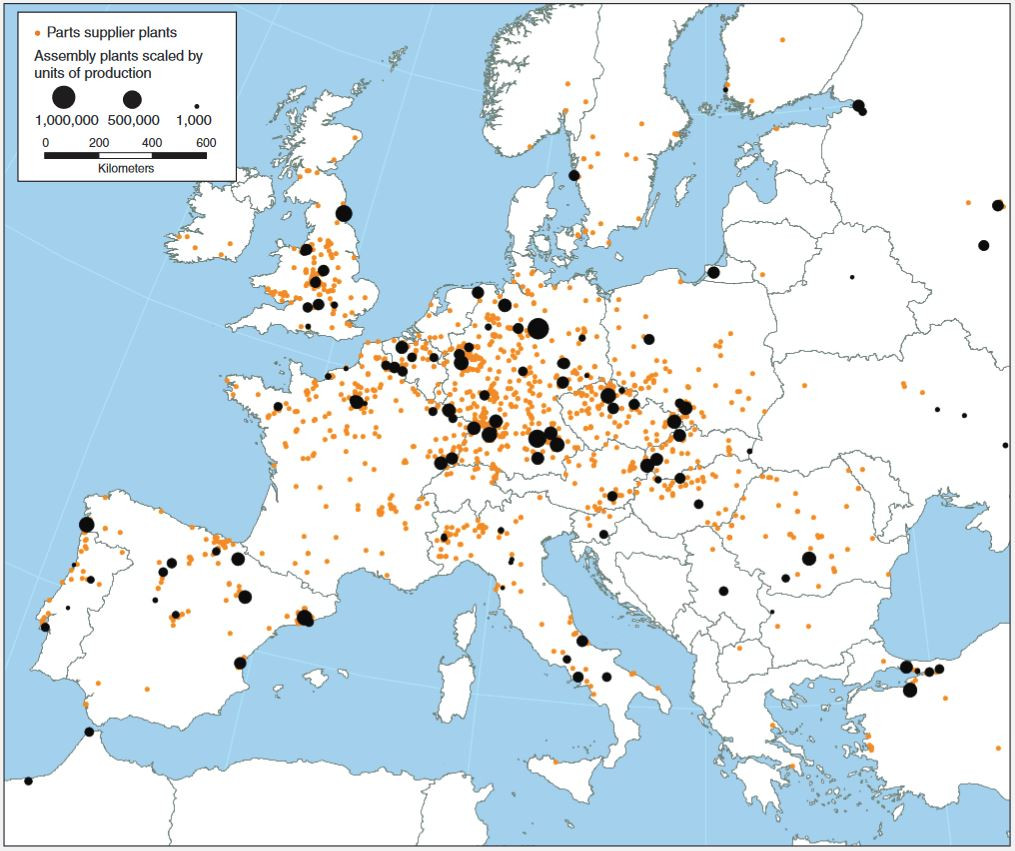

Regional concentration

The region's car industry is concentrated around central and eastern Europe, as illustrated by the following map that includes assembly plants (black) and suppliers (orange).

Total direct automotive manufacturing employment is highest in Germany by far with around 882,000 jobs, followed by France (229,000), Poland (214,000), Romania (191,000), the Czech Republic (181,000), Italy (176,000), United Kingdom (166,000), Spain (163,000) and Hungary (102,000), according to ACEA figures.

Given their relatively smaller total population, the share of direct automotive employment in total manufacturing is highest in Slovakia and Romania with almost 16 percent each, followed by Sweden, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Germany, with the EU average standing at 8.5 percent.

Many large automotive players – both carmakers and suppliers - use eastern Europe as extended workbenches given the relatively lower wages there. For example, in the Czech Republic this trend has made the automotive industry the biggest industrial sector that accounts for more than nine percent of GDP, 26 percent of manufacturing and 24 percent of Czech exports, according to the country's business and investment development agency Czechinvest. Many foreign car industry investors produce in the country, as illustrated by the following graph.

Suppliers more vulnerable than carmakers

Media coverage of the upheaval in the car industry has largely focused on the embattled carmakers. But it appears likely that the continent's massive supplier industry will be the focus of projected changes to employment because many companies – especially smaller ones, which are often extremely specialised – have much less scope to adapt. In total, the supplier industry also employs more people than the carmakers themselves.

The European Association of Automotive Suppliers (CLEPA) says it represents over 3,000 companies, and that automotive suppliers directly employ 1.7 million people in the EU. The industry generates more than 250 billion euros in annual sales and provides five million direct and indirect jobs, according to the lobby group.

The automotive supplier industry is extremely diverse, as it includes multinational corporations with hundreds of thousands of employees, but also countless small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Three of the world's five largest automotive suppliers are German: Bosch and Continental claim the industry's highest revenue, with ZF Friedrichshafen ranking fifth. The only other EU members in the global top ten are France’s Michelin and Valeo, ranking ninth and tenth, respectively.

Of the world's top 100 suppliers by revenue, more than a third are headquartered in Europe. Again, Germany dominates the field with 18 companies on the list, followed by France (6), the UK (3), Italy (2), Spain (2) and Ireland, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands and Luxembourg (1 each), according to a ranking compiled by management consultancy Berylls.

Again, it currently looks likely that large multinational suppliers can weather the transition more easily than smaller industry players, because they have many more options to diversify and expand in growth areas, such as electric mobility. Still, these companies face tremendous challenges, as illustrated by Europe's top three suppliers:

- Bosch already announced thousands of job cuts and far-reaching restructuring plans several years ago due to waning demand for diesel and petrol cars. The company currently has around 400,000 employees. Some 50,000 of these depended on the diesel technology in 2019 (15,000 in Germany). This division has come under particularly intense pressure due to the "dieselgate" cheating scandal and air pollution issues in many cities. Bosch said in early 2021 it is speeding up the shift to electric engines, which is turning into the cornerstone of the company's propulsion division with growth rates of almost 40 percent. In contrast to a growing number of truckmakers, Bosch also bets heavily on hydrogen fuel cell trucks. The company's CEO, Volkmar Denner, has hit out at the EU for being "fixated" on electric vehicles, insisting that "climate action is not about the end of the internal combustion engine" but "about the end of fossil fuels." Bosch currently plans to continue to invest in combustion engine technology "for at least another 20-30 years."

- Continental warned in late 2020 that the transition to electric vehicles was happening too rapidly and at the expense of people's livelihoods. The company told the Financial Times new environmental regulations were coming too fast to compensate for employment losses. The company said in September that the technological shift put 30,000 of the company's 230,000 jobs at risk worldwide (13,000 in Germany).

- In contrast, ZF Friedrichshafen believes new orders for electric cars will more than make up for losses sustained by the shift away from combustion engines in the next few years. ZF has so far earned most of its money with automatic transmissions, but electrification means it is also becoming an engine manufacturer. Its new "Electrified Powertrain Technology" division already has more than 30,000 employees, 42 plants and generates around ten billion euros in sales. The company said last year it would no longer develop components for combustion engines and would focus instead on plug-in hybrids and pure electric vehicles.

"Technology neutrality" as a lifeline?

The suppliers' troubles in the shift to electric mobility explain why German car industry association VDA rejects a sole policy focus on electric mobility and instead calls for a "technology-neutral" approach. Echoing Bosch’s comments cited above, the lobby group insists that only fossil fuels rather than combustion engines are a problem for the climate. European supplier association CLEPA also insists on "technology openness."

Given that the use of synthetic fuels made with renewable electricity in combustion engines could throw a lifeline to many companies focused on conventional technology, the VDA argues that modern combustion engines and synthetic fuels "will play a major role" in achieving the climate targets. But the VDA's stance is highly controversial even within the industry, leading to a deep split within the lobby group. The VDA's biggest member Volkswagen has opted for a battery-only strategy and has been highly critical of the VDA's insistence on remaining open to which technology will make the race. Volkswagen and many green mobility proponents argue that a clear focus on the rollout of electric mobility is required to speed up emission cuts in the sector, partly because battery-electric cars use energy much more efficiently. In contrast to many suppliers, Germany's two other major car groups -- BMW and Daimler -- are now also fully committed to battery-electric vehicles.

Decline à la Detroit in Germany's car regions?

Given the massive size and status of its car industry, the employment impact of the shift to e-cars has been widely discussed in Germany, and the country's experiences in the shift will offer valuable lessons for its neighbours with a strong auto industry presence. Especially in eastern Europe, opposing trends are at work: On the one hand, the supplier industry with a strong presence in these countries is set to undergo major restructurings, some of which will entail job losses. On the other hand, carmakers and suppliers alike use the shift to relocate the production of electric vehicle components to these countries, potentially boosting employment, anecdotal evidence suggests.

With a view to the dramatic decline of the US car industry in recent decades, unions have warned that Germany faces "a few small Detroits" in regions with a high concentration of embattled supplier companies. German car industry states Bavaria (home to BMW and Audi), Baden-Württemberg (Daimler and Porsche), and Lower Saxony (VW) called on the European Commission in late 2020 to keep the impacts on SMEs in view while deciding on new fleet emission limits. The industry and politicians say the shift to electric mobility must not be disruptive, but instead a gradual transformation so companies and employees have enough time to adapt.

Numerous recent studies have looked into electrification's overall employment impact in Germany and beyond:

- Germany's National Platform Future of Mobility (NPM), a government advisory body, said in a report in early 2020 that more than 400,000 jobs in the country’s car industry could be gone by 2030 in a worst-case scenario involving a rapid switch to electric vehicles. The report was widely covered in German media. The country's car industry association VDA rejected the findings, saying they presented an "unrealistic and extreme scenario." Fears of many hundreds of thousands of job losses in the industry have subsided somewhat since then, as carmakers' and major suppliers' efforts in low-emission mobility have gained traction.

- An oft- cited study by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) found in 2020 that there is little difference in the number of personnel and amount of work involved in building an electric car and a vehicle with a combustion engine. Fewer workers are required to build the engine alone, but not the whole car, because e-mobility requires new production steps, such as battery cell and module production and packaging, as well as power electronics and thermal management of the battery. Vehicle assembly or laying the wires are also more labour-intensive for electric cars than for vehicles with combustion engines, according to the study. But the authors said the fact that battery cell production currently largely takes place abroad is a problem for jobs in Germany. They added that new factories to produce e-mobility components are often built in eastern European countries to save on costs.

- A study commissioned by Volkswagen and conducted by the Fraunhofer Institute for Organization and Industrial Engineering compared VW's plans for the manufacturing of conventional vehicles and electric cars in late 2020 and concluded that "job losses from the introduction of electric mobility are likely to be substantially lower in the area of vehicle manufacturing than global studies have predicted." The researchers expect employment in this area to fall by 12 percent in this decade, mainly due to output volumes and higher productivity. But while the study suggests employment impacts at the carmakers will only be limited, it also indicates that the supplier industry could face significant job losses. "With respect to component manufacture, however, labour requirements are 70 percent higher for the production of a conventional powertrain than for the production of a powertrain for an electric vehicle," the study says. It concludes that "there is no uniform employment trend in the 'transformation corridor' over the coming decade. Instead, there will be a complex, interconnected mixture of job creation, job upgrading and job cuts." It argues that it will be vital to ensure that SMEs do not fall victim to this reorganisation.

- The Institute for Economic Research (Ifo) found in early 2021 that the number of internal combustion engine jobs in the German car industry that will be affected by the shift to electric cars will significantly exceed retirements in the years to come. In a study commissioned by car industry association VDA, the institute estimates that at least 178,000 employees currently depending on combustion engines would be affected by the transition by 2025, while only 75,000 would retire. The authors stress that the "affected" employees will not necessarily lose their jobs, but they would at least have to adapt to new roles. The study also does not take into account the creation of new jobs associated with the transition, for example in battery or electric motor production. By 2030, the shift would affect at least 215,000 combustion engine employees, compared to 147,000 retirees, Ifo said. The study says the shift to electric cars will hit employment with a delay, because companies currently maintain parallel production structures for combustion engine and electric models.

- The CAR Center Automotive Research at Duisburg University found in early 2021 that more ambitious EU car emission limits would only endanger a relatively small number of jobs in Europe's car industry. "Planned EU tightening of CO2 requirements endangers jobs in the European auto industry less than feared – on the contrary: across all sectors positive effects on employment can be expected," said author Ferdinand Dudenhöffer. In Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Slovakia, the tightening of emission limits would cause less than a combined 28,000 direct job losses, corresponding to less than two percent of combined automobile employment in the five countries, which represent 70 percent of EU car production. But these will be more than compensated for by the creation of new jobs, CAR predicted. In Germany alone, the new Tesla plant near Berlin and other announced battery cell plants are set to generate more than 35,000 new jobs by 2025 "excluding wider employment effects in mechanical engineering and electrochemistry in Germany," while around 15,000 existing car industry jobs could be lost, CAR said.

- A joint analysis by think tank Agora Verkehrswende and the Boston Consulting Group found that the shift to electric mobility could turn out to become a boon for the German car industry that creates jobs rather than destroy them. Moreover, the economically weaker states of eastern Germany could emerge as the biggest winners from the transition away from combustion engine technology over the next decade, the organisations said. Even though the shift to electric cars will bring momentous changes to the German automotive industry over the next decade, the number of jobs in the car sector could broadly stay at the same level as today and even slightly increase, they said. "There will be a significant growth in jobs in the producing and supplying industries for companies that are independent of traditional propulsion technology," Agora Verkehrswende said. Together with new jobs in the energy infrastructure sector, energy production and also in plant manufacturing, the shift to e-cars could create up to 205,000 new jobs. At the same time, around 180,000 jobs would eventually be lost in companies that rely on combustion engine technology to a high degree, resulting in a positive net effect of roughly 25,000 jobs.