Germany faces packed election year as voters weigh climate against pandemic recovery

The year 2021 looks set to become a watershed for Germany's political landscape with potential ramifications for the country's energy and climate ambitions, as long-term Chancellor Angela Merkel plans to step down after 16 years after the general election scheduled for next autumn. Merkel's departure as the leader of Europe's largest economy and the ensuing scramble for the leadership of her conservative CDU/CSU alliance have set the scene for an election with more uncertainty than arguably any other in the country in the past decades.

Climate policy is still poised to loom large in the vote that comes at a time when Germany faces fundamental decisions that will determine the progress of its energy transition and also the success of the European Union as a whole on its path to greenhouse gas neutrality by the middle of the century. Driven by huge protests from the Fridays for Future movement, Merkel's conservatives and their coalition partner, the Social Democrats (SPD), launched a set of emissions reduction policies in their Climate Action Programme in late 2019, which included plans to boost emissions reduction by supporting clean and efficient technology and introducing a price for carbon emissions across the board. The scene seemed set to turn the 2021 vote into Germans' verdict on energy and climate policy in their country.

Just a few months later, the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic profoundly shook government plans in Germany as much as anywhere else, with the subsequent crunch on worldwide economic activity fuelling fears that ambitious climate action could fall prey to hurried solutions to cushion the financial impact of the virus. How well Germany's national as well as European climate plans can be reconciled with the pandemic's social and economic consequences will be determined in the national debate during the coming months of campaigning.

"Without the COVID-19 crisis, I would probably have said we're going to have a 'climate election'," sociologist Sebastian Koos from the University of Konstanz told the Clean Energy Wire. "I'm more sceptical now whether it will be the central issue." However, Koos also said the pandemic is far from turning voters' concerns upside down and he is confident climate policy will remain a key issue in the 2021 election. "Voters seem ready to keep it up as a long-term concern. Each party therefore will have to lay out a vision how they intend to deal with the topic," he argued.

Surveys conducted in the months after the outbreak repeatedly showed that the fight against global warming continues to play a huge role for citizens, businesses and parties despite the economic turmoil caused by the pandemic. "I expect the climate debate to remain a central issue regardless of how the coronavirus crisis evolves," climate researcher Brigitte Knopf said. The physicist is secretary general of the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC) and heads the policy unit in the Ariadne project on Germany’s energy transition. She has also been appointed to the government's national expert council on climate issues charged with overseeing the progress in emissions reduction.

"Things that appeared unthinkable last time will play an important role"

Knopf told the Clean Energy Wire that climate as an election issue had irrefutably gained a lot of ground compared to the previous vote in 2017, when there were "nearly no debates on the topic." The 2017 elections were dominated by the fallout from the so called refugee crisis and the rise of the right-wing populists. Since then, Germany has seen two consecutive years of severe droughts and heatwaves; hundreds of thousands of people march in the Fridays for Future climate protests; an unprecedented rise of the country's Green Party in the polls; and the hard-fought end to coal-fired power production. "Many things that appeared unthinkable last time will now play an important role," Knopf said.

At the same time, the outgoing government remains under pressure to successfully navigate the ongoing energy transition challenges. While the cuts to energy consumption due to the economic collapse in the wake of the coronavirus lockdown appear to allow Germany to edge much closer than expected to its 2020 target of reducing emissions by 40 percent compared to 1990, structural challenges remain to a steady cut in CO2 emissions. A key factor is the ailing expansion of renewables, which have become Germany's number one power source and are scheduled to cover 65 percent of demand by 2030, up from about 43 percent in 2019. The country’s new solar PV and wind power installations that are needed for the ambitious emissions reduction measures like the mass introduction of electric vehicles and boosting green hydrogen production have lagged far behind required levels.

According to government adviser Knopf, Germany's coronavirus recovery programme has been a case in point for the sense of urgency that has captured the country's climate policy. Instead of rolling back hard-fought climate compromises to give companies more wiggle room amid the pandemic, there were "clear commitments to upholding and strengthening the climate programme and cut support for emissions-intensive technologies," she said, citing the exclusion of combustion engines from support payments in the coronavirus recovery as a "milestone" from a climate policy perspective. The decision that stunned the country's prized but also rattled car industry also demonstrated a broader change of heart in the country, she said. "There appears to be a growing understanding that smart economic policy doesn't keep jobs on life-support that would vanish in five years anyway."

Companies bank on steady climate policy

Developments at the state level seem to validate the assessment that deeper structural change is firmly under way in the German economy. With elections in no less than 6 out of the 16 states in the highly federalised country, 2021 will also see a slew of voter judgments on the state governments' performance in reconciling emissions reduction and the energy transition with a healthy restructuring of local economies. Such regional votes are also often seen as a test of the public's perception of the parties on a national level. And even local and municipal elections, like the ones in coal-mining state North Rhine-Westphalia - germany's most populous state and home to the CDU's leadership candidates - on Sept. 13 may provide first pointers for the year ahead.

The country's northern coastal states, which have a renewable power production edge over traditional industry centres in the south thanks to their large wind power capacities, vie for a piece of the pie of Germany's strong industry base by taking a pole position in the country's ambitious National Hydrogen Strategy. The strategy aims for leadership in a technology many regard as a key energy transition tool awaiting a massive scale-up. Similarly, the decision by US e-carmaker Tesla to put its first European factory in Brandenburg, a coal mining state heavily affected by the fossil fuel's phase-out, shows both that structural change can commence quickly and that German carmakers are given a run for their money in the emerging e-car market's partition.

Knopf argued that the key task for any successor to the current 'grand coalition' government of Merkel's conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the Social Democrats (SPD) therefore is to ensure that climate policy decisions can materialise by quickly putting in place the required technologies and reforming its still often "absurd" regulatory framework for energy taxation and renewables expansion. "This will be a key challenge for the next government." These tools are needed to underpin a trend among companies from all sectors of the economy as well as for households to implement emissions reduction in earnest. Many companies have by now made a general commitment to stringent climate policy, she said, adding that "there seems to now be a critical mass of them that would be irked by regulatory U-turns."

Indeed, announcements by company alliances such as the 2° Degree Foundation, in which industrial heavyweights like Volkswagen, Siemens or ThyssenKrupp all endorsed a recovery programme that is built around the goal of greenhouse gas neutrality, show that a different tone in the German climate debate seems to have gained a foothold. Amid the pandemic, most companies showed no sign of watering down their climate plans, analysts at the CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project) found, often because following their original emissions reduction and energy efficiency plans is expected to save costs and gives access to cheaper bank loans, a trend that is set to intensify along with the further development of Germany's green finance plans.

A general agreement by parties in possible government coalitions on the need for a reform of the set of taxes, premiums, surcharges, rebates and levies could be found relatively quickly, regardless of how the next government is set up, as this will be needed to truly allow the CO2 price and other measures to lure consumers away from fossil fuels. However, a consensus on how exactly the system could be reformed and also whether Germany needs to pull more of its weight in EU climate efforts will probably be more difficult to find – and will depend greatly on the ultimate party constellation.

Leadership contests within parties add extra drama

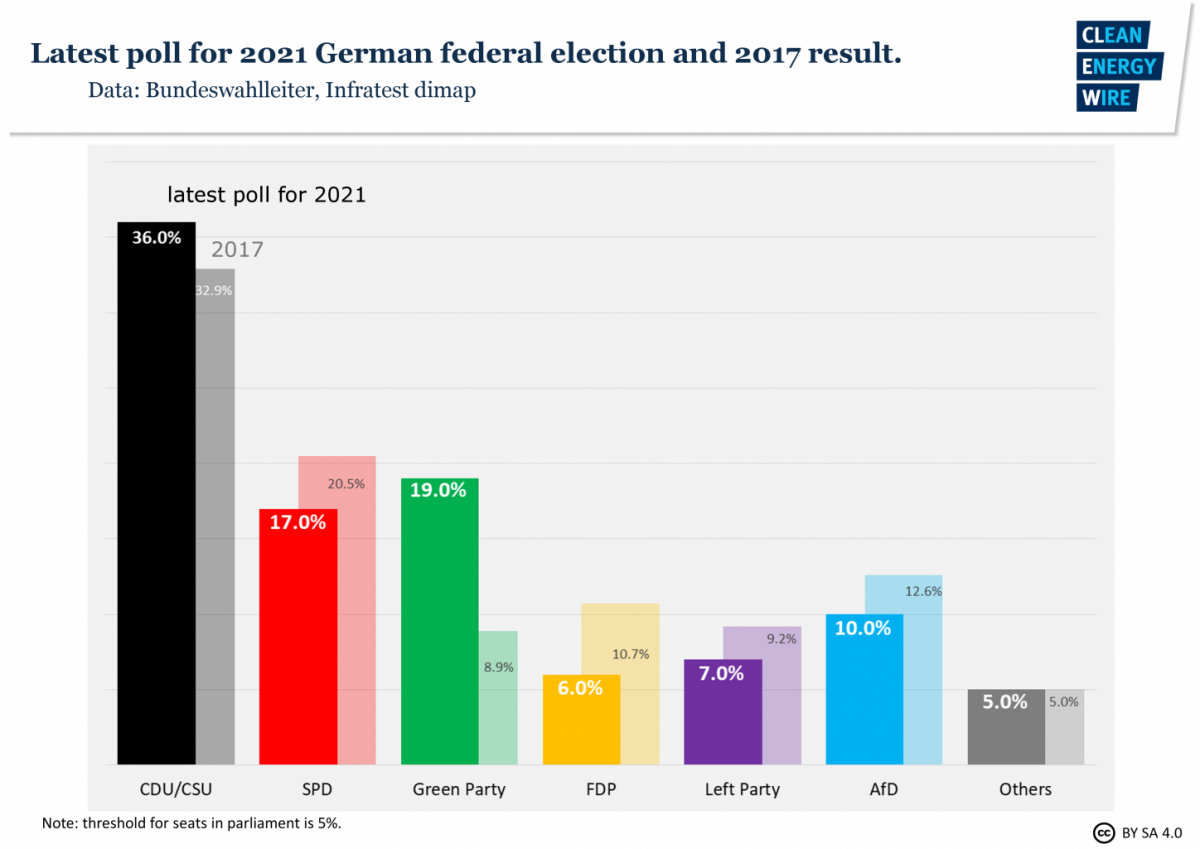

A continuation of the coalition between the CDU/CSU and the SPD seems unlikely at this point. Merkel's conservatives have been reaping most of the credit for the government's generally lauded coronavirus response. While the conservatives managed to jump from 26 percent in voter support in early March to 40 percent in the polls by mid-June, the SPD, which only very reluctantly entered the coalition after losing badly in the 2017 election, hoover at around 15 percent. At the same time, the Greens established themselves as the second strongest party, constantly polling ahead of the SPD at nearly 20 percent.

As both the Left Party and the pro-business FDP are stuck well below 10 percent and the right-wing nationalist AfD has been ruled out as a partner by all other parties, a CDU/CSU-Green Party coalition look the most stable outcome in terms of majorities a year before the ballot. While the two parties govern together in various coalitions in a number of states, this constellation has never been tested on a federal level. German media have speculated about the chances of this option frequently and the parties themselves have not ruled it out. They also worked noticeably smoothly together in the 2017 'Jamaica coalition' talks that eventually collapsed because the third party involved - the FDP - pulled out.

But how well Merkel's party with its core support groups among the elderly and the rural population will be able to function together with the Greens and their markedly younger and more urbanised base at the federal level will to a large extent hinge on outstanding leadership questions in both camps. Among the conservatives, CDU candidates Armin Laschet, state premier in coal state North Rhine-Westphalia, and Friedrich Merz, a former CDU parliamentary group leader who is favoured among the party's more conservative wing, are seen as the most likely candidates for succeeding Merkel and both vie for CDU leadership that is set to be determined at a party convention in December.

Another contender for leading the conservative camp is Markus Söder, state premier of Bavaria and head of the CSU. Despite not commenting on ambitions so far and regardless of the fact that politicians from the CDU's Bavarian sister party are traditionally being eyed more critically among voters from the rest of the country, Söder has the highest approval rating of all conservative hopefuls, not least thanks to his steadfast reaction to the coronavirus outbreak. The Green Party, on the other hand, looks set to field one of their two party leaders as candidate for chancellor: Annalena Baerbock or Robert Habeck. Baerbock is considered a pragmatist who could successfully broker a coalition with the conservatives and sell it to more sceptical parts of the party base. Habeck in turn is the more popular candidate among voters overall.

The SPD, meanwhile, decided to move early and nominated popular finance minister and vice chancellor Olaf Scholz as its candidate. The move is seen as a nod to the party's centrist credentials after having chosen two more left-wing politicians as party leaders at the end of last year. However, Scholz has said he does not seek to continue the coalition with Merkel's conservatives and instead entertains the idea of a leftist coalition with the Greens and the Left Party.

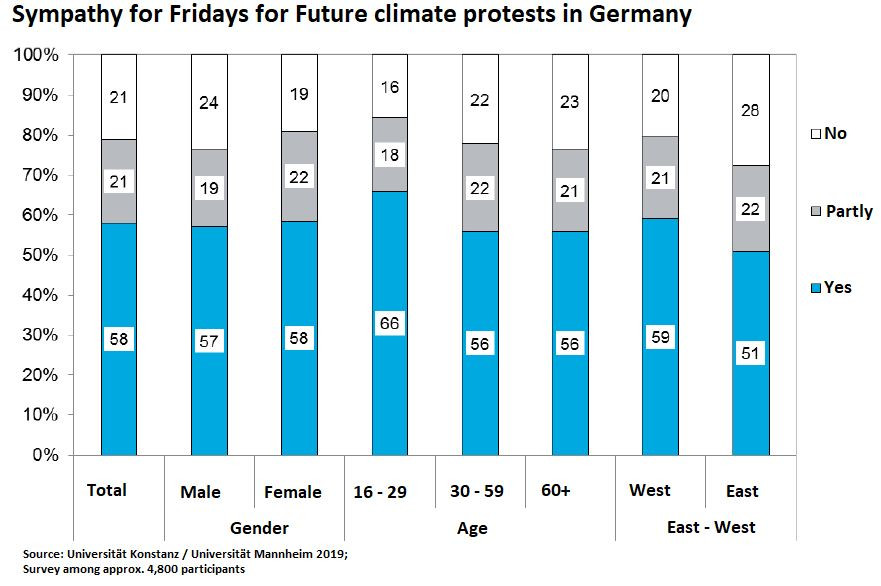

Balancing COVID fallout and climate action "litmus test" for parties

Climate action is set to figure prominently on voters' minds regardless of which party constellation eventually agrees on forming a government. "Climate change certainly is a topic that no party in Germany's parliament will be able to avoid," protest researcher Sebastian Koos said. He cautioned that the pandemic's economic impact on the country would make it likely that social fault lines are going to widen in the coming months, meaning a good balancing of social and ecological questions could become "a sort of litmus test for the parties how they manage to reconcile their approaches." But climate is not likely to lose out to other considerations among voters. The researcher closely analysed the Fridays for Future protests last year, which according to Merkel had already nudged the government to shift up a gear in climate policy.

What started out as a student movement inspired by Swedish activist Greta Thunberg had slowly morphed into a broader movement of climate protesters from all strands of society, the researcher argued. "The more well-known these protests became, the more their demographic composition approached that of German society in general." Of course, he added, the protests also elicited a counter reaction from those who outrightly deny the severe effects of climate change, for example the AfD. "But even among these groups you see some support for the protesters and for goals like a CO2 tax."

Even though the restrictions on mass gatherings have reduced the movement's visibility in recent months, bar a brief meeting of Thunberg and fellow activists with Merkel, Koos said the attitude in society had by no means subsided. The authenticity of the young peoples' concerns over their future had turned them into credible representatives of climate activism. This in turn had prompted a true and possibly lasting shift in the thinking of a great portion of the population, increasing their willingness to put up with more regulation and shoulder costs that will inevitably accrue as a result of emissions reduction. "This has been quite difficult to imagine for a long time," Koos said.