The Energiewende's booming flagship braces for stormy times

Onshore wind power in Germany

Contents

Industry accustomed to success poised for a sea change

“We should get going. Every hour this thing stands still costs us between 500 and 1,000 euros.” Wind energy project developer Andreas Ehrenhofer wants to get the nearly 150 metres tall wind turbine near Berlin back on the grid and gently asks to finish our visit to the top. The machine needs to be stopped if any visitors or workers take the tiny two-person elevator all the way up. On a mildly windy spring day like today, this can be an expensive trip for the operator.

Ehrenhofer works at Teut Engineers, a small company that develops, builds, and operates a handful of wind parks like the one in Ahrensfelde, just north of the German capital. Teut Engineers became active in wind power installations in the late 1990s, a time when renewable energy generation started to fully gain traction in the country.

“We started doing this out of the idea to become an agent of change and to contribute to the transition to clean and potentially unlimited energy provision,” Ehrenhofer says. “And also because we realised that political conditions were very favourable for this venture at the time.”

Teut Engineers has not been alone in taking advantage of Germany’s Energiewende policies, which are aimed at supporting the country’s gradual transition towards renewable energy sources and a low-carbon economy. The age-old technology to harness the wind’s energy potential has been made a central component of this shift. But a set of political and social changes, as well as technological constraints, could hamper wind power’s unabated growth in the country.

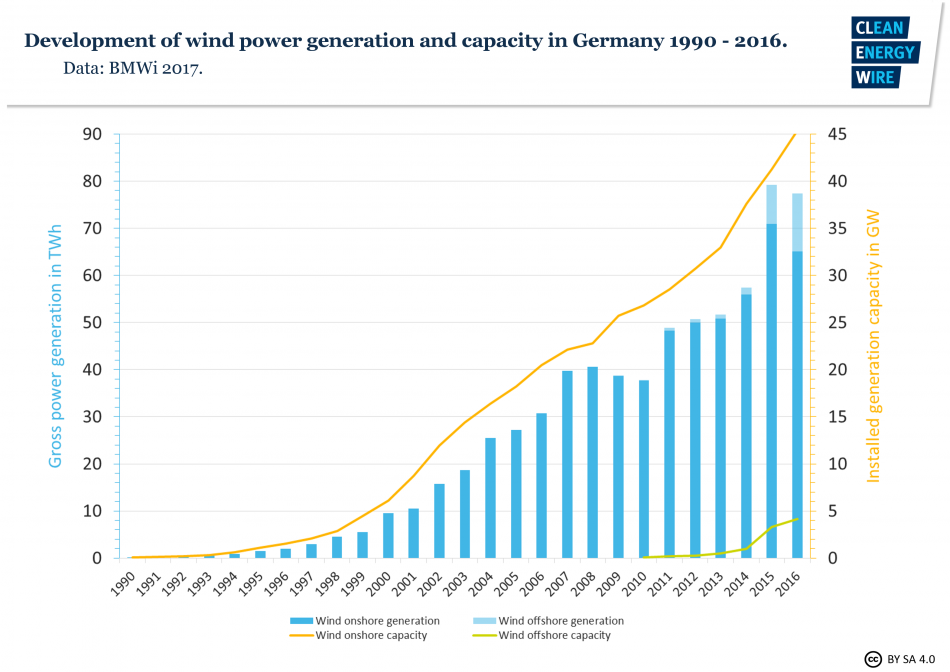

Germany’s onshore wind power industry started out in 1990 with a handful of rather experimental installations producing about 71 gigawatt hours (gWh) – roughly the demand of a small town. It has grown to a multi-billion euro business that in 2016 poured out nearly 80,000 gWh of electricity, capable of powering over ten percent of the world’s fourth largest economy, or the equivalent of almost 23 million average households.

“We currently are in a very lucky position,” says Wolfram Axthelm, spokesman of the German Wind Energy Association (BWE). “Our wind power industry just had its second-best year ever in terms of expansion in 2016.”

With the manufacturers’ and project developers’ order books filled, the recent domestic expansion boom will be sustained until at least 2019, Axthelm estimates. If all projects registered by Germany’s Federal Grid agency (BNetzA) are put into practice by that time, wind power capacity across the country will further grow by almost 20 percent to more than 52,000 megawatt (MW).

But despite the industry’s boom and impressive turnover, the BWE spearheaded a campaign themed “Save the Energy Transition!” in 2016. The lobby group argued it was “five minutes to midnight” for ensuring the sector’s survival. In the association’s latest market analysis, BWE head Hermann Albers said Germany’s total wind power capacity might soon decline. He warned the government not to miss crucial objectives for increasing the share of green power and bringing down Germany’s carbon emissions.

How does this alarming rhetoric match with the solid performance recently shown by the industry? One answer is that the current spate of activity is triggered by a profound change to the country’s central renewable power support scheme.

Due to changes in the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) aimed at a greater exposure of renewables to market forces, newly built installations will no longer receive guaranteed remuneration paid by customers via their power bills.

Investors were therefore eager to submit as many construction applications as possible before last year’s deadline. From 2019, they must compete in auctions where bidders requiring the lowest subsidy amount are awarded the contract. It marks a momentous change for a sector that enjoyed publicly sponsored financial planning security for years, paving the way into wind power for Teut Engineers and many others.

The changing subsidy structure is only one of several challenges for an industry relied on by the government as a backbone of the Energiewende. The lagging expansion of high-voltage transmission lines, which are needed to supply wind power from productive locations to industrial centres, also poses a barrier to expansion [See the CLEW dossier The energy transition and Germany's power grid for more information].

Other constraints include the windmills’ grid compatibility, as well as finding appropriate storage solutions that help to bridge times of dead calm [See the CLEW factsheet How can Germany keep the lights on in a renewable energy future?]. The wind power industry’s own success has led to a growing number of windmills, which has sparked controversies over the turbines’ effects on the landscape and the health of humans and wildlife. [See the CLEW factsheet Fighting windmills: When growth hits resistance]

The forging of a flourishing sector

Germany’s onshore wind power industry may await a watershed in terms of funding, but it has benefitted from a supportive industrial policy to overcome its infant status. The rapid expansion in Germany has been the result of targeted policy design, effective engineering, and also widespread public enthusiasm.

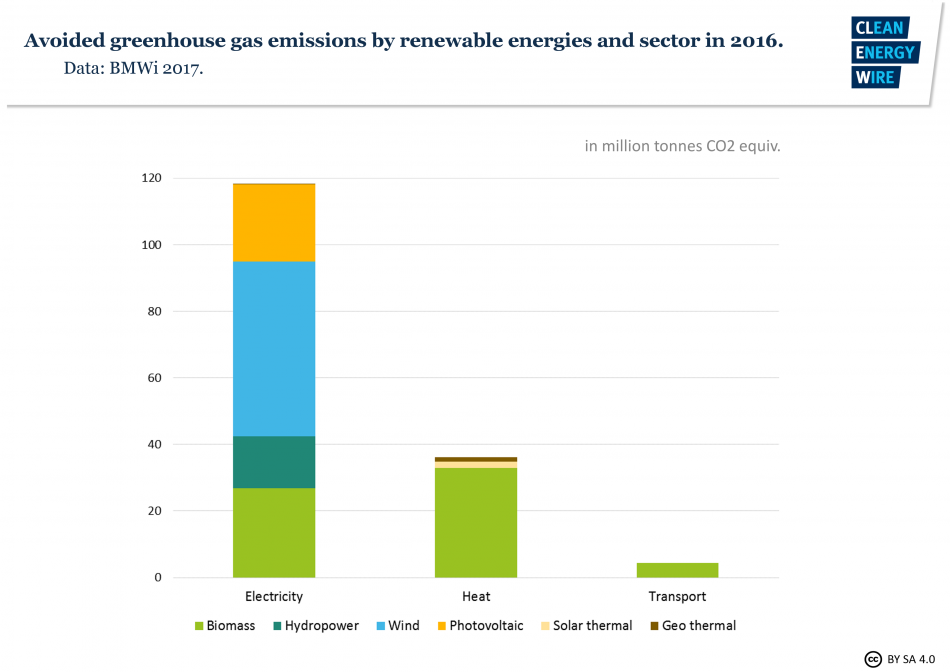

Germany is a vocal supporter of the Paris Climate Agreement and concerted international action to limit the man-made effects on climate change. The nation will continue to depend heavily on the wind power sector to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 80 percent until 2050 and derive 60 percent of gross final energy consumption in all sectors from renewables, as outlined by the Federal Environment Ministry (BMUB).

Onshore wind power currently contributes ten percent to Germany’s power mix, by far the largest chunk among renewables. Windmills have for many become an Energiewende figurehead because of their visibility and straightforward mode of operation. The industry’s ascent, however, did not happen by accident.

In 1990, a predecessor to the EEG guaranteed financiers of wind turbines and other renewable energy sources, ranging from private households to institutional investors, feed-in tariffs above wholesale market prices, fixing returns in advance for 20 years. The bill had been introduced by the Green Party together with the conservative union of CDU/CSU, an early sign of renewables’ dual appeal to conservationist and entrepreneurial ambitions alike. The concept was then refined by the Social Democrat-Green government in the EEG in 2000, giving green energy feed-in precedence, and further amended until 2016 with the shift to auctions.

“The EEG had been decisive for wind power’s breakthrough,” says Thorsten Lenck, project manager at energy policy think tank Agora Energiewende*. “The feed-in law was meant to give small operators access to the grid, which was dominated almost exclusively by big energy providers back then,” he explains.

Profit margins for wind power installations at the time were far smaller than those of conventional fossil and nuclear power plants, typically less than ten percent on average. Big companies, therefore, largely refrained from investments, according to Lenck. This opened a niche for smaller private investors, such as municipalities, citizens’ energy cooperatives, or small project developing companies, which consequently made up the bulk of wind power operators, he says.

Providers were able to pass on costs for renewable installations to power customers, totalling roughly 50 million Deutschmark – about 25 million euros – in the first year. The European Commission was at first suspicious of illegal subsidies and demanded the policy be amended. But the European Court of Justice subsequently ruled the subsidies were lawful. Eventually, the Commission explicitly endorsed the concept. Today, support schemes akin to those in the EEG have been emulated in over a dozen European countries. In Germany, remuneration within the law’s framework amounted to about 25 billion euros in 2016, according to the country's four major grid operators.

Turning for turnover

[See CLEW factsheet German onshore wind power - output, business and perspectives]

“In absolute terms, no other sector benefitted as much from Germany’s renewables support policy as wind energy,” Lenck says. Investments grew continuously over the years, amounting to almost 10 billion euros in 2016. This equalled two thirds of all investments in renewables in the country, according to figures provided by the Renewable Energies Agency (AEE). Driven mostly by domestic demand, the on- and offshore wind industries chalked up a turnover of around 13 billion euros.

Germany has been constantly leading in terms of absolute onshore wind power expansion rates in Europe over the last years. Theoretically, the installed capacity already covers more than half of the country’s total power demand of about 85 GW [See the CLEW factsheet Germany's energy consumption and power mix in charts for background]. But volatile weather conditions mean windmills typically only produce a fraction of their potential maximum output.

The Renewable Energy Research Association (FVEE) estimates that wind turbines’ electricity generation costs today could already compete with conventional power plants if built at very productive locations. “With the technology available today, two percent of the surface area in all federal states would be sufficient” to cover up to 65 percent of total power demand, the researchers say.

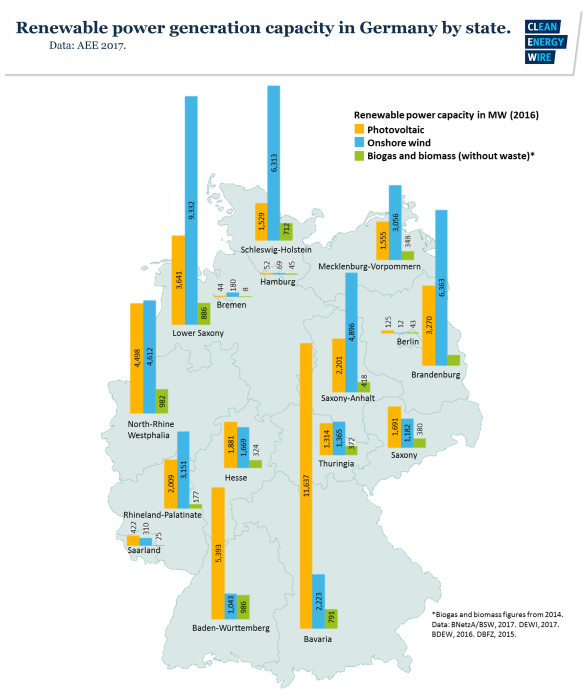

Regional differences in wind consistency, and therefore productivity, shaped the distribution of turbines, and consequently also the economic trickle-down across the country. Earlier models are not as capable of exploiting weak winds as efficiently as their modern successors. This means most windmills today are found in the country’s northern plains and coastal regions, where steady breezes blowing in from the sea are often stronger and more predictable than in Germany’s rather hilly south.

However, this distributional disparity is set to taper off as technological progress means it is possible to operate windmills at a profit at locations with less favourable wind conditions. Contrary to previous years, wind power expansion has therefore taken place “more and more evenly distributed across the territory” with southern states catching up, according to wind industry association BWE.

“The wind industry has achieved a lot in terms of weak wind turbines,” says Po Wen Cheng, holder of Germany’s first professorship for wind energy generation at the University of Stuttgart. “Plants can now also be operated profitably in regions with little wind,” he explains.

Felix Rehwald, of turbine manufacturer Enercon, agrees: “The wind power yield per turbine has increased almost fifteen-fold since the 1990s,” he explains. New turbines by Germany’s market leader from the small town of Aurich, near the North Sea coast, now provide more than 13,000,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity per year at locations with average wind conditions – enough to power 3,500 average households.

A case for more competition: Tendering the Energiewende

[See CLEW factsheet High hopes and concerns over Germany's onshore wind power auctions]

The prolonged expansion diminished wind energy’s aura of a nascent industry requiring special treatment by policymakers. Wind power and other renewables no longer needed to be “handled with kid gloves”, former economy minister Sigmar Gabriel argued last year. He said it was time the technology exposed itself to more competition and demonstrated it can assert itself in open competition.

The state, therefore, will no longer provide state-set remuneration for future renewables projects. Facing fixed expansion volumes, the market is supposed to adapt by demanding the lowest possible remuneration in auctions.

At the same time, support rates for projects completed in a two-year transition period will gradually decline, putting pressure on developers to get new wind parks to feed into the grid as quickly as possible. The average remuneration per kWh provided in February this year still stood at more than eight cents and will decline to seven cents by late 2018 – a difference that can easily amount to several tens of thousands of euros less annual support per windmill.

Remuneration in the first round of onshore wind power auctions amounted to 5.71 ct/kWh on average, over a quarter lower than the fixed amount in early 2017. According to Rainer Baake, state secretary in the Federal Ministry for the Economy and Energy (BMWi), the auction showed “the paradigm shift from fixed support rates by the state to a market-based price setting has worked well.”

Auctions for offshore wind power projects, which due to the more challenging geographical conditions are essentially constrained to large-scale projects, showed even greater cost effects: Investors offered to build their wind farms without any support at all.

Nevertheless, the BWE and the German Engineering Federation (VDMA) warn the switch might lead to a drop in installed capacity after 2020 when the 20-year remuneration period for the first windmill generation ends. The groups are eager to convince the government to ramp up projected expansion volumes.

The lobby groups say this is the only way to ensure that Germany meets its cross-sectoral renewable energy targets, which rely on wind power to a great extent and cover power production, heating and the transport sector, where an envisaged large-scale shift to electric vehicles is likely to significantly raise the country’s power demand over the next decade.

Critics also argue that the EEG’s reform aimed at attaining cost efficiency faster is going to have adverse effects on actor diversity. Costly auctions are said to give bidders with larger financial reserves an edge over smaller competitors, such as citizen energy projects or locally rooted small to middle-sized enterprises and municipal utilities.

The economy ministry has vowed to “maintain the diversity of actors” by making projects with a capacity of up to 750 kilowatt exempt from the auction mechanism – while the average modern turbine boasts a capacity three times bigger than that. For experienced small-scale wind energy developers like Mr Ehrenhofer from Teut Engineers, this provision is unlikely to prevent a shift in the investors’ structure. He says: “Projects of this size are not economically viable.”

But citizens’ energy cooperatives turned out as the “big winners” in the first onshore auction, according to state secretary Baake. Citizen projects, which have to consist of at least ten people, the majority of whom live in the region where the wind park is built, managed to secure the vast majority of the tendered volume.

However, Stefan Gsänger from the World Wind Energy Association (WWEA) warned it was too early to judge whether the high share of citizens’ projects would actually turn out to be a success: “We’ll have to wait and see how many projects are going to be implemented in the end.”

Clogged corridors against decentralisation demands

Turbines are also expected to undergo better systemic integration and to better contribute to grid stability. Due to the uneven allocation of installations between the sea and the Alps, the federal grid agency regulated expansion volumes for Germany’s northern states far more tightly than in other parts of the country. Slowing down growth is needed, it argues, to ensure that grid expansion across the country remains on par with installed capacity increase.

The sheer number of turbines, plus their expansion in size, increases system load. This makes the transmission of constantly rising amounts of power from the north to industrial centres further south more difficult. Greater transmission volume and more flexibility to absorb power from intermittent wind power plants are therefore necessary.

The prevalence of installations in the north makes the transmission highway “SuedLink” necessary, large utilities and the German wind industry association argue. But the project initially scheduled for completion by 2022 is likely to be delayed by at least three years due to ongoing protests by affected local populations to put the high-voltage cables underground.

“There’s no alternative to transmission grid expansion and we cannot afford any further delays,” the BWE’s Axthelm says. Permission procedures for construction and reinforcement of transmission corridors had to be eased, the industry representative argues.

“Grid conduciveness has become the most important feature for wind power plants in Germany,” he explains. Remote turbine control was necessary to make sure the installations contribute to a stable line frequency, but Germany's manufacturers were making good progress in this regard, he says. With the EEG’s reform, the government incentivised wind park operators to opt for larger and more capable installations and also to replace older windmills with modern ones.

The so-called “repowering” of turbines would also improve wind power’s flexibility, Axthelm adds. Especially in the north, modern installations could significantly improve efficiency of wind farms. Installed capacity on average is two times greater than in old models, according to the BWE. They also tend to have lower noise emissions and feed into the grid more steadily and project developers benefit from past experiences when orchestrating the turbines’ arrangement.

Wind turbine manufacturers continue looking into various options to increase grid conduciveness, ranging from better responsiveness to changing wind patterns, to the integration of storage solutions in new projects. “We’re developing interface technology to connect our installations to power-to-gas systems or to directly provide electricity for e-cars,” Enercon’s spokesman Rehwald says.

“Plant operators would like it best if their installations fed in around the clock,” he explains. But since electricity generation contingent on weather conditions could not yet guarantee full availability, integrated storages offered a way to simultaneously provide greater grid flexibility and new possibilities to create turnover for operators, Rehwald says [For more information, see CLEW factsheet Volatile but predictable: Forecasting renewable power generation]. Since surplus wind power is usually greater at night, when electricity demand is low, charging e-cars during this time meant operators could calculate with more constant purchases of their electricity, he says.

Wind power researcher Cheng says exploiting the technology’s full potential is not possible without reinforcing the grid for centralised supply. “But a decentralised approach also has a lot of advantages,” Cheng argues.

To produce power in the regions where it is consumed would reinforce local acceptance and also reduce the transmission lines’ length, which improves efficiency. It would also help spread the risk of adverse wind conditions over a larger area, Cheng explains. “You won’t find too strong or too weak winds everywhere at the same time.”

He therefore calls for reinforcing both long-distance transmission and short-distance distribution networks. “Grids used to be one-way roads for top-down distributions,” he says. But decentralised power production changed this pattern and meant that power also flows back from households: “This is a much more complex system. And it will inevitably require more management and intervention.”

From cooperatives to corporations – the operators

[See CLEW factsheet From survey to harvest: How to build a wind farm in Germany]

The question of which grid system is most suitable for ensuring stable renewable power supply also alludes to the key issue of the Energiewende’s ownership.

Millions of regular citizens have become electricity providers by putting solar panels on their roofs, biogas plants on their land, or by investing in nearby solar and wind installations. More than 800 citizen energy cooperatives and small enterprises were able to break into the market and challenge the unabated authority of a few major energy companies over Germany’s energy supply.

Agora Energiewende’s Lenck says the diverse ownership structure had been fostered by the reluctance of major utilities to engage in decentralised energy supply systems. Compared to profit margins in conventional systems centred on large power stations, dispersed wind, solar or biogas plants offered nothing but “peanuts” for the top dogs’ accounts. “Private investors settled for a lot less,” he explains.

But the windmills’ comparative profitability could drastically increase if the price on CO2 emissions rose to “adequate levels”, Lenck adds. Many installations currently could not be sustained without governmental support, but this was due to low wholesale energy prices caused by excess capacities stemming from already written-off fossil plants.

Industry observers share the impression that the tides could be turning in onshore wind power’s ownership structure. More than 90 percent of Germany’s 4,300-plus wind parks are still operated by small project developing companies and public initiatives, according to the BWE. But market-listed green power providers and institutional investors ramped up their holding by as much as 500 percent in 2016.

Kerstin Mann, project manager at wind park developer VSB, says a shift towards larger ownership entities has become increasingly evident throughout recent years. She says that the trend differs regionally, as citizen initiatives in northern Germany were still more engaged in continuing their activities and invested in repowering of existing installations.

Some small and medium-sized operators tried to counter the new support regime’s difficulties by resorting to turbine bulk orders to receive quantity discounts. “But this is no single antidote. Every location needs individual planning, which makes up-front turbine orders very impractical,” Mann argues.

But Germany’s wind power market already produced a spectacular case that could serve as a warning to overly eager investors: Fuelled by onshore wind power’s boom in the early 2000s, wind park project developer Prokon attracted large numbers of investors with a cumulated capital of 1.4 billion euros by promising fantastic returns. Doubts were raised over the company’s business model and investors demanded their money back. Prokon’s subsequent insolvency created investor losses of over 40 percent. In 2015, shareholders transformed the company into Germany’s largest citizen energy cooperative.

Engineering veterans challenge fast climbers – the manufacturers

The prevalence of small-scale pioneers during the emergence of Germany’s onshore wind power industry was not limited to project development. The design and manufacturing of modern wind turbines also largely rested with initially-small companies.

Manufacturers and their suppliers, especially in northern Germany, were riding a wave of favourable political and societal conditions coupled with rapid technological progress to quickly climb to the top of a new industry branch.

Three out of four of Germany’s largest wind turbine manufacturing companies did not even exist in 1980. Today, German producers account for about a fifth of global production and “consolidated their position among the innovation-driven industries of the future”, as business and engineering associations VDMA, BWE and OWIA put it.

The bulk of the country’s windmills are built by domestic providers: Enercon still leads the German market with approximately 40 percent of all new installations and roughly half of all existing turbines. The onshore-only supplier is followed by competitors Nordex and Senvion, with about 15 per cent and 7.5 percent of new onshore installations respectively.

Notable foreign suppliers in Germany are Danish company Vestas and US manufacturer General Electric, which together accounted for more than one third of all new onshore installations in 2016.

Due to the government’s supportive policies, wind turbine producers sprung up like mushrooms in the 1990s. The ensuing fierce price competition saw many companies disappearing or being bought, according to database The Windpower.

The international financial crisis of 2008 then forced many countries to lower renewables support schemes, leading to further market consolidation. “Remaining manufacturers were able to substantially recover and make up leeway,” business journal Handelsblatt noted in 2013.

Stiff competition and the fight for self-preservation sometimes left its mark on the wind pioneers’ desired appearance as likeable and eco-friendly newcomers. Innovation-trailblazer Enercon, for example, which rose from a garage company to a multi-billion dollar enterprise within some 20 years, made headlines when a dispute over labour rights ended with a number of employees active in the workers’ council leaving of the company.

Today, Germany is still home to more than a dozen manufacturers and almost every international producer maintains a sizeable presence in the country. They seek to benefit from its central location close to important on- and offshore markets, entrepreneurial and legal reliability, and from business cluster effects, according to state-owned foreign trade agency Germany Trade & Invest.

But it is far from clear whether onshore wind power’s boom years in Germany can be sustained. “Margin pressure almost certainly will increase,” Heiko Stohlmeyer, of business consultancy PwC, says. “But there will be efforts to compensate this by focussing on innovation.”

Several major manufacturers lately showed signs of contraction despite the industry’s recent uplift. In March, Senvion announced it was going to reduce the number of employees by about 15 percent, with production sites in Germany bearing the brunt of the cut. In the same week, Nordex CEO Lars Bondo Krogsgaard resigned amid “disappointment” with the company’s expected performance.

These problems might foreshadow a trend reminiscent of the operating sector: industry veterans with deep pockets sweep the market. The merger between Spanish global player Gamesa and the wind power branch of German engineering giant Siemens, concluded in early April, points in that direction.

Growth of global green power demand spells tailwind for German industry

Germany has provided a fertile environment for onshore wind power’s development for over two decades. But while the technology was able to maturate within the scope of the Energiewende, recent political and economic trends suggest the sector’s domestic growth could be at least slowed.

The latest decrease in turnover of the country’s onshore wind power companies was mainly caused by a drop of almost a quarter in domestic investments, according to a study commissioned by the economy ministry. Researchers, including the Fraunhofer ISI and German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), say growing business volumes abroad largely compensated the domestic decline and limited total contraction to about five percent.

To achieve global carbon emissions reduction levels as stipulated by the Paris Agreement, wind and solar power have to increase from less than five percent of worldwide electricity generation today to over 30 percent by 2040, according to analysts Caroline Cook and Rinesh Bansal of Deutsche Bank Research.

PwC’s Stohlmeyer says price signals from the first offshore tenders showed how economically mature the technology has become. “This is going to motivate even more countries to emulate,” he predicts.

The Global Wind Energy Council in 2016 put the world’s year-on-year capacity increase at 23 percent. At the same time, German exports in the sector grew by nearly 30 percent, the BMWi’s study says. In the previous year, another study commissioned by the ministry found that German manufacturers struggled to keep track with expansion volumes and increased international production capacities in order to not miss out on business opportunities.

“We export our products to 35 countries around the world,” Enercon’s Rehwald says. A dispute over patent rights in the US in the 1990s, and another in India some ten years later made the company wary of the potential pitfalls lurking beyond the well-regulated German and European markets. But Enercon is confidently extending its activities in Brazil, Canada, South Korea, and other parts of the world.

International customers appreciate the quality of German engineering in wind power as much as they do for premium vehicles, often giving the country’s producers an edge over lower-cost competitors, researcher Po Wen Cheng says. “Wind power turbines require a lot of know-how,” he explains. Unlike with PV systems, differences in manufacturing quality matter greatly, Cheng says.

Similarly, German experience in planning, maintenance and marketing of wind power can be appealing abroad: “Our experience and technical expertise is certainly helpful abroad,” says VSB’s Mann. Her company has also been active outside Germany for many years, planning and implementing wind parks in neighbouring European countries like France or Poland.

“But we wouldn’t want to come across as arrogant German know-it-alls,” she says. “That’s why we usually have partners from the host country, often subsidiaries, who carry out legal and business aspects,” Mann explains.

So will the world’s growing appetite for clean energy relieve Germany’s onshore wind industry of the cooling-down at home? Average export quotas of about 70 percent give reason for this conclusion. But another set of order boosts is not guaranteed abroad: China, the world’s most important wind power market, is “difficult to access”, PwC’s Stohlmeyer says.

In the US, President Donald Trump’s stance towards renewables puts a question mark over their sustained success in the country.

According to calculations by the Fraunhofer ISE, a future energy system in Germany could rely on an onshore wind power capacity of up to 200 GW – more than four times its current volume. “Germany remains our most important showcase-market,” Rehwald says.

*Like the Clean Energy Wire, Agora Energiewende is a project funded by Stiftung Mercator and the European Climate Foundation.